LOGAN — Before the curtain rises on Grey Gardens, the voice of W. Vosco Call, who founded the Lyric Repertory Company more than fifty years ago, gives the pre-show announcement reminding patrons to silence their electronic devices. This echo from the past is a great thematic segue into this musical about the change in fortune wrought by time and isolation on Jackie Kennedy Onassis’s reclusive aunt and cousin, both named Edith Bouvier Beale. As I’ve written before, I remember seeing shows directed by Call in the ’80s, back when the space (constructed in 1913), while not run down, did show its age a little more. In the inverse of the dilapidation that thirty-odd years bring about on the Beales’ East Hampton mansion known as Grey Gardens, the Lyric is impressively restored these days and there is even a much younger Call serving as one of its co-artistic directors.

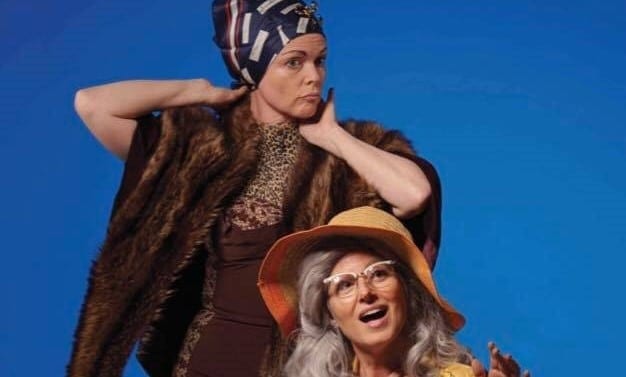

Yet, nothing seems to have changed about the fire in its soul, which can also be said of the Beales, who are devastatingly realized across three decades by Tamari Dunbar, Clarissa Boston, and Karen Bruestle. Anchored by these thrilling performances, director Jim Christian’s vivid, penetrating take on Grey Gardens completely swept me away.

The musical version of Grey Gardens by Doug Wright (book), Scott Frankel (music), and Michael Korie (lyrics), which premiered on Broadway in 2006, is partly adapted from and partly inspired by the 1975 documentary of the same name. The second act tracks the film closely, providing a window into the lives of the mother-daughter pair — known as “Big Edie” and “Little Edie” — in 1973. Their eccentric existence amid squalor, cats, and fleas in a decaying mansion brought them to the attention of the county Board of Health, which soon attracted the notice of the National Enquirer due to their family connection with Jackie Kennedy. The first act is set in 1941 and presents a fictionalized vision of the two Edies when they still belonged to the pinnacle of society and Little Edie was engaged to Joe Kennedy, Jr. (which didn’t actually happen, but gives the audience a point of reference for their social prowess at the time).

It would be difficult to give spoilers even if I wanted to, as there are few distinct events or major plot points to reveal. Rather, the book and songs flow among the relationships between characters. This mostly involves the two Edies, but also extends to Joe Kennedy, Major Bouvier (Big Edie’s father), the musician George Gould Strong, a local man named Jerry Torre, and a young Jackie and Lee Bouvier. Explanations don’t really do it justice, but the show absolutely works. Everything unfolds in a manner both seamless and organic, with a sophisticated score and dialogue that feel fully realized as one artistic whole instead of component pieces.

Fortunately, the sophistication of the material is equaled by an extraordinary cast. Boston, as Little Edie in the first act, shows impressive range in making the whiplash of her relationship with Big Edie believable. Dunbar plays both sides of this dysfunction in dual roles as Big Edie in the first act and Little Edie in the second, imbuing each character with their own distinct dimensions of a trapped and heartbroken spirit in songs like “Will You,” “Around the World,” and “Another Winter in a Summer Town.” In the last of these, she is joined by Bruestle as Act II’s Big Edie, whose performance reveals cracks of vulnerability that have widened over the years.

Trent Dahlin provides some excellent onstage piano playing while hinting at the depths that George Gould Strong tries to mask with one-liners. Terence Goodman, as Major Bouvier, delivers bracing bluster and a master class in intonation. Mitch Shira, confident and polished as Joe Kennedy in the first act, undergoes a remarkable transformation into the disheveled, soft-spoken, and kind handyman Jerry Torre in the second. Most importantly, though the actors allow the comedic aspects of the script to shine through, they never veer into cheap, D-list celebrity voyeurism. While not shying away from the absurd, Christian has coaxed motivated and genuine interactions from the actors that always err on the side of empathy for the characters.

I’ve written before that the Lyric Theatre may be my favorite venue in the state, and it’s a great fit for a show like this. The eerie creaking piped through the house speakers before the curtain, with a ghostly image of the decrepit Grey Gardens projected on the scrim, feels right at home in the Lyric’s intimate, historic space. Its age allows it to host the grandeur of yesteryear and the shabbiness it later becomes equally well. It sounds great too: Not only is the cast more than up to the demands of the score, but I am delighted to report that this production features live musicians and that Bryan Z. Richards’s sound mixing is superb. I won’t say there weren’t a few technical wrinkles (e.g., some flubs from the pit and a wainscot that doesn’t follow the line of the stairs), but they are entirely transcended by performances of such verve and complexity.

However, there is one similarity between the Lyric’s Grey Gardens and the story of the Beales that must be erased. This exceptional cast performed opening night to a mostly empty house. The size of the audience notwithstanding, the actors gave it everything they had. To my knowledge, this is only the second time this show has ever been produced in the state (the first was Wasatch Theatre Company in 2011), and the real tragedy here is yours if you miss this production. At times harrowing, at times poignant, you couldn’t ask for a better opportunity to visit Grey Gardens.

[box]The Lyric Repertory Company production of Grey Gardens plays July 12, 14, 18, 31, and August 3 at 7:30 PM and July 28 at 1:00 PM at the Caine Lyric Theatre (28 West Center Street, Logan). Tickets are $30-35. For more information, visit lyricrep.usu.edu.[/box]

Donate to Utah Theatre Bloggers Association today and help support theatre criticism in Utah. Our staff work hard to be an independent voice in our arts community. Currently, our goal is to pay our reviewers and editors. UTBA is a non-profit organization, and your donation is fully tax deductible.