SALT LAKE CITY — The true story of Edith and Little Edie Bouvier Beale is the stuff American legend. In the 1940’s the mother-daughter duo were promising New England socialites with enough money, connections, talent, and charm to mark them as American royalty. Thirty years later they would be discovered living as recluses in their 28 room mansion surrounded by filth and 52 cats. They would pass through national scandal and into documentary stardom, eventually being rescued from their horrid living conditions by their close relative Mrs. Jacqueline Bouvier Kennedy Onassis.

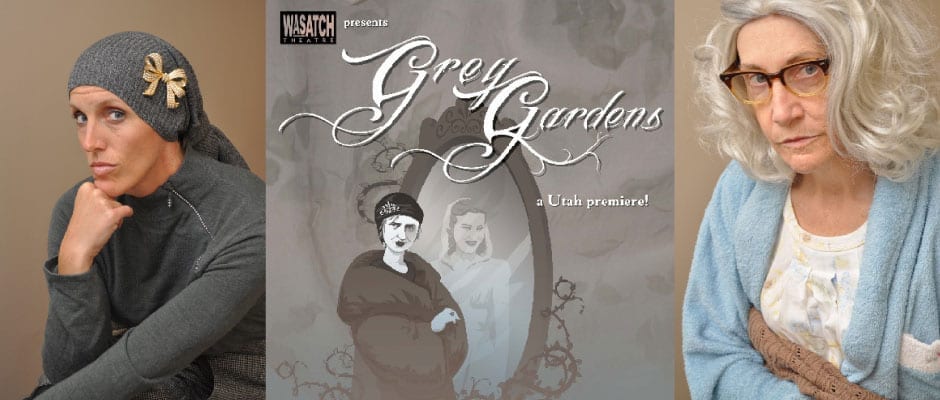

Grey Gardens, which premiered on Broadway in 2006 and received 11 Tony Nominations tells the story of these two remarkable women on two distinctive days from their life together. Despite a valiant effort, The Wasatch Theatre Company’s production of Grey Gardens fails to shed light on this captivating story. The subtle quirks and tenderness required to tell a story of complex familial relationships and crippling mental illness were sadly lost in the enthusiasm and lack of subtlety of the performers.

The intimacy of Rose Wagner Black Box theatre seems an ideal location for the small cast musical. As act one opens. Grey Gardens, the posh estate the Bouvier Beale’s inhabit, is in furious preparation for the engagement party of young Edie to Joseph Kennedy, Jr. A quarrel begins between mother and daughter when it is discovered that Big Edie (Jennifer Perry), with the help of her live in accompanist and companion George Gould Strong (Eric McGraw), has prepared a nine song congratulatory concert for the happy couple’s guests—against everyone’s wishes. Young Edie, played by Ali Goldsmith, flits about the stage in an unexplained swimsuit and a constant furrowed brow attempting to convince her mother to give up the concert. We are then introduced to the Bouvier patriarch (David Tucker) who gives us the entertaining, but lackluster, song about the aristocratic requirement he places on his granddaughters, including the little girl characters of Jackie O and her sister Lee (Grace and Ella Pilling respectively) to “Marry Well” (if not chaste, at least in haste). Once the groom-to-be (Luke Monday) enters, the tension mounts as we begin to see just how desperate Little Edie is to escape Grey Gardens, and how far Big Edie will go to keep her daughter by her side.

The orchestra of a piano and keyboard are nicely placed in audience view and out of the way of the action by scenic designer Kit Anderton’s simple, but effective, two-level unit set. The musical score of the show is an eclectic variety of styles. The first act draws deeply from pre-WWII American standards. Songs like “Two Peas in a Pod, Going Places” were charming, but floundered outside Goldsmith’s range. The politically-incorrect-to-the-point-of-cringe worthy coon song “Hominy Grits” was a horrifying delight. This song provided Darryl Stamp, playing the kind hearted person of color house-keeper named Brooks, a standout moment without even opening his mouth. Though vying for the smallest role in the cast, Stamp somehow managed to grab much of my attention with his elegance, compassion, and vocals each time he entered the stage. The most memorable songs in the score, “Will You?” and “The Girl Who Has Everything” showcased Perry’s soulful searching and frantic desire to keep things “just as they are.”

After the initial excitement of the peppy second half opening songs, “The Revolutionary Costume for Today,” and “The Cake I Had,” Ms. Perry, now portraying a middle aged and mentally troubled Little Edie, and Sallie Cooper, playing the aged Big Edie, both fall victim to the sleepy and disjointed feeling of the back half of the show. This slowing down may be an unavoidable product of the score, or the lack of a full orchestra. Perhaps it was musical director Rick Rea’s attempt to reflect the stagnant and twisted lives of the two now older Edies. Act two is a long sequence of slow ballads including the very awkward “Jerry Likes My Corn,” the lovely “Around the World,” and the dry “Another Winter in a Summer Town.” Even the hand clapping gospel number “Choose to Be Happy” couldn’t revive my spirits at this point. I applaud Ms. Cooper’s vocal prowess. She filled Big Edie, who could easily become a whiny caricature of a crazy woman, with three dimensional longings and wit. If the script or director George Plautz had allowed Ms. Cooper to leave center stage bed, I have no doubt she could have single handedly put the show on her shoulders and carried it through to the end.

Grey Gardens’ script and score are clear in their goal of exploring the devastating effects that love and co-dependency have on these women’s lives, but Wasatch Theatre Company’s production left me with more questions than answers. Where there might have been strong acting choices, there was confusion of intention. Where there could have been foreshadowing and character arc, there were only clouds and hazy ideas. Where there ought to have been humor and gut wrenching tenderness, there was primarily bombast and “look how crazy we all are!”

Almost as a warning, The Grey Gardens playbill was prefaced with the Wasatch Theatre Company’s mission statement. The company makes no bones about using limited resources and their desire to encourage experimental work in a supportive, classroom like, environment. They hope “to increase awareness of, respect for, and participation in theatre.” They may find these goals to be challenging if they do not present a product that an audience outside the classroom can enjoy.

[box type=”shadow”]The Wasatch Theatre Company production of Grey Gardens plays at the Black Box Theatre in the Rose Wagner Performing Arts Center (138 W. Broadway, Salt Lake City) Thursdays, Fridays, and Saturdays at 8 PM and Saturdays at 2 PM through September 24. Tickets are $15. For more information, visit wasatchtheatre.org.[/box]