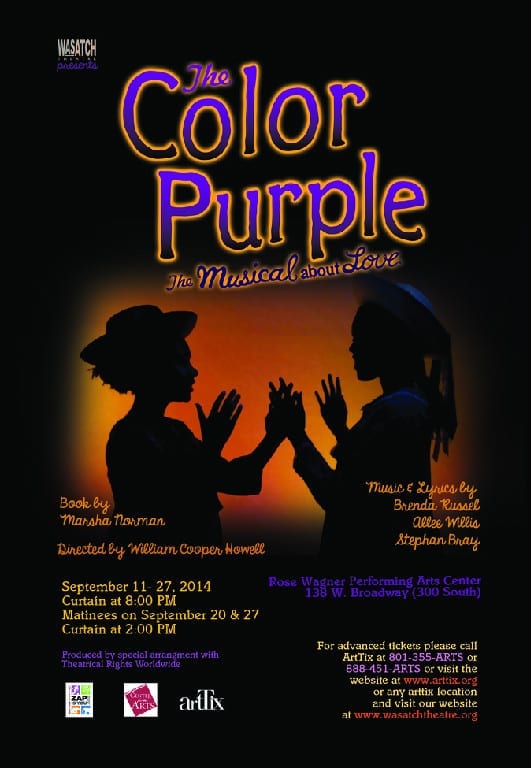

SALT LAKE CITY — One theme that all people can relate to is the search for one’s ipseity, or identity. It is a universal struggle, and a journey explored in the novel The Color Purple by Alice Walker (adapted into a musical by Marsha Norman, Brenda Russell, Allee Willis, and Stephen Bray).

The play tells the story of Celie, an unfortunate woman who finds herself the victim of tyrannical men who deprive her of her freedom and dignity. Forced into marriage at a young age by her “father,” she is then stripped of the only person who loves her, her sister Nettie. Her two children are also taken away by her “father,” whose rape of Celie brought about the birth of the infants, a boy and a girl. She must then endure a marriage with Mister, an abusive and cruel man, who sees her as nothing more than a servant and nursemaid to his children with a previous wife. When Celie finds love with an affluent and charismatic woman named Shug Avery, her circumstances begin to change for the better.

In the lead as Celie, Latoya Rhodes delivers a powerhouse performance, tapping into the weaknesses, strengths, tenderness, and torment that the role demands. Not only is her singing voice sublime, but Rhodes’s interpretation of the downtrodden woman that transforms into a battleship of ferocity was layered and raw, grabbing me from the moment she slouched onstage, her shoulders bent in an attitude of compliance and passiveness, until the moment she stands Mister down, cursing him, her posture tall and straight, her chest thrown out and her voice ringing with fortitude and force. It was not Celie’s plight alone that brought me to tears at various points throughout the show, but also the utter honesty in Rhodes’s portrayal.

The play deals with racial and gender identity, and it is indeed the women of this story that ruled the stage, providing humor and lightness alongside devastation and hardship. There were many and varied roles for women in this play, which I appreciated as well. One interesting juxtaposition was a scene in which the female ensemble sang an anthem of empowerment, and in the next scene, an infantilized woman (Squeak, played by Jenny Rock), waltzes into an all-male scene, wearing a giant pink bow and carrying an oversized sunflower. She prances around cloyingly, a child-like seductress who clashes with the liberated women in the previous scene.

Included in the diverse female roles was a trio of “church ladies” served as a kind of humorous and judgmental Greek chorus, punctuating the play with their narrations and thoughts on the plot, and they were a delight. Also peppered throughout the play were some robed choir singers, soloists who acted as angelic emissaries, offering a hopeful and repeated prayer. I was enchanted by the voices of these soloists, who provided a level of grace to the material. However, one problem with the play was that soloists were often overpowered by the volume of the chorus, which was substantial. Malinda Money, as Shug, was often difficult to hear, which was a shame, as her voice and performance were quite lovely.

As Mister, Lonzo Liggins was able to play a character that could have easily been painted a monster with traces of humanity and relatability. Though he was, through the first half of the play, genuinely intimidating and at times terrifying—particularly in the scene wherein he threatens Nettie with rape, carries out violence against her and Celie, and then carts her off against her will—in the second act, his process of redemption and contrition was visible and clear. Even in Liggins’s posture was an exact foil of Celie: he began the play straight and tall, and became more and more bent as his humility increased. Another standout performer was Erica Richardson as Sofia, the headstrong and bold-as-brass woman who serves as an example of defiance against men to Celie. Her song “Hell No,” packed a spirited punch, and was as funny as it was empowering.

With recent events in mind, it is, I believe, imperative to explore the telling of race issues through period theater. Certain media outlets would have mass audiences believe that racial differences belong in the past. Yet, I became emotional thinking of how the tribulations displayed in this story were just as relevant today—how Sofia’s incarceration for asserting herself as a liberated Black woman echoes not only from the past, but in the treatment of this particular ethnicity even in the 21st century. My reaction would not have been possible without William Cooper Howell‘s focus on the emotion of Celie’s words. It is one of the many reasons that this work is important and valuable. The Color Purple also deals with homosexuality, a theme that rings out as plaintively as the soulful music interwoven into Walker’s words.

An aspect of the production that I enjoyed was the costuming, skillfully executed by Linda Eyring. Not only did the costumes have to evolve through advancing time periods, but they had to visually allow the characters to evolve, particularly in the case of Celie. Celie stars out in drab colors and functional dresses, the faded yellow of her frock almost like a dandelion that has been trodden underfoot one too many times. As the play progresses, the colors of her wardrobe become brighter, and she dons pants, her gender and sexual identity becoming more assertive. In the end, as she stood in her purple suit and head scarf, she looked positively royal.

Such is the nature of this play that I would recommend it to anyone hoping to glean an emotional education. I was quite drawn in to this powerful story, and it is sure to stay with me for a long time.

[box type=”shadow”]The Wasatch Theatre Company production of The Color Purple plays every Thursday, Friday, and Saturday at 8 PM and every Saturday at 2 PM through September 27 at the Rose Wagner Center for the Performing Arts (138 W. 300 S., Salt Lake City). Tickets are $20. For more information, visit www.wasatchtheatre.org.[/box]