OREM — The conflict between faith and state for Archbishop Thomas Becket, religious adviser to King Henry II of England, is central to Murder in the Cathedral. T.S. Eliot’s classic script focuses on the events of Becket’s life between December 2 – 29, 1170, primarily honed on the internal struggles of the archbishop. Following a seven year exile to France, Becket returns to England with hopes of political peace surrounding his return. However, there are concerns that Becket’s return could anger the King, and only lead to further political strife.

Like Christ in the New Testament, Thomas confronts three temptations in his return, and must battle the seduction each offers. A fourth temptation—martyrdom—appears as a new enticement, pulling the Archbishop in with an alarming persuasion. Thomas admits he’s considered martyrdom, though finds it best to accept God’s will as the penultimate judgment. Eventually, Thomas is murdered by four knights, at apparent behest of the king, and the play turns into their trial. A lingering reminder remains, though: had the Archbishop not used religious power to undermine the State, his death would not have been necessary.

I appreciated the heightened sense of theatricality used in this performance. T. S. Eliot’s language brings a very poetic flow to the action of the play, and it can be easy to lose track of plot in the words. However, overt gesticulation and caricatured means of acting had a storytelling feel. And while I initially disliked this choice, the starkness of actors using their real voice—as opposed to the previous recordings—brought a weight to scenes where voiceovers were not used. The contrast of overtly-acted scenes with a more natural feel to others really served to highlight parable versus personal strife.

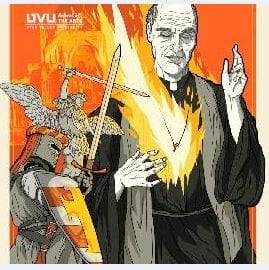

This same sense of meta-theatricality reflected in makeup (Janessa Law-Fulton), with prominent contouring visible on all actor’s faces. The very brightly colored costumes (Clarissa Lavon Knotts) fit well with the fashion of the early 1100’s. I particularly enjoyed the lavish use of color and opulence in the costuming of the tempters, which reminded me, again, that this was a highly theatrical production. And while this initially didn’t sit well with me, there was something jarring about the notion of a man’s death being staged in such a formally dramatic setting. The presentation of Becket’s story—such heavy content matter juxtaposed with the usual levity of performance—ultimately resonated. The women’s costumes were the only puzzle, and looked like echoes of Greek fashion (perhaps playing upon the notion of a Greek chorus?), which marked them as separate from other players.

I thought that the directors (Benjamin Henderson and Lisa Edwards) made some bold choices in this show. Pre-recorded voices were amplified (although the volume levels were too loud sometimes), and actors seemed to lip-sync to their own roles. I thought the pace moved along pleasantly, clocking in at roughly forty-five minutes, but many of Eliot’s more clever phrasings were lost to the relentless pull of poetry. Pre-recorded bits had a strong tempo, fast and forcing the action along at an almost furious pace; the surely chaotic mindset of Thomas Becket reflected in the speed of performance, and I could only feel pity for the man being swept up into the unfolding politics around him. However, there were times when I couldn’t quite catch on fast enough who was meant to be speaking, and missed some lines. But for the most part, wide gesticulation visually drove the story along.

It is difficult to single out any actor in this piece, as Murder in the Cathedral relied strongly on ensemble work. Indeed, the cohesive moment and choreographed moments of action worked to great effect. I appreciated the seamless blend affected by the members of the cast, to create a heightened world of reality. Their collective work made the piece intriguing to watch, and—though still confusing at times—the commitment to wide gesticulation and theatricality worked to great effect. Combined with the contrast of more grounded moments, and more intimate aspects of audience address (that is, the knights speaking directly to the audience), I thought the players controlled the energy of the crowd well.

All in all, I enjoyed my experience with Murder in the Cathedral. I found that, despite a highly elevated form of performance, the story still resonated and I was left with the same weight of emotions that a more grounded show might have provided. The contrast between choreographed, removed moments and more intimate intensity provided a jolting shift, and kept the energy dynamic in performance. It can be difficult to compete with outdoor elements, but I thought the actors did a good job of keeping my attentions. More savoring of T. S. Eliot’s words might have served well, or perhaps a snippet of history or plot synopsis in the program might have alleviated some confusion. (I heard some people after the show question what exactly had just happened. ) But ultimately, I enjoyed the performance and was intrigued by the directors’ performance method. Anyone seeking a change in the norm of theater might easily find satisfaction in this show, and with a short run-time and low admission fee, it’s an easy show to catch.

[box type=”shadow”]The final performance of Murder in the Cathedral plays September 16 at 5 PM in the courtyard of the Sorensen Student Center on the campus of Utah Valley University. Tickets are $3-5. For more information, visit www.uvu.edu/theatre/events/theaterevents.php.[/box]