CEDAR CITY — In a royal court full of glamorous women, elegantly dressed servants, and impeccably well mannered men, “something is rotten.” Not far beneath the surface of this high society, there lies a decaying core. Treacherous (and supernatural) events occur that expose the amoral men and women for what they truly are and lead to the downfall of almost everyone involved. This timeless tale of betrayal and revenge is told in the Utah Shakespeare Festival’s production of Hamlet, which runs through October 27 in Cedar City.

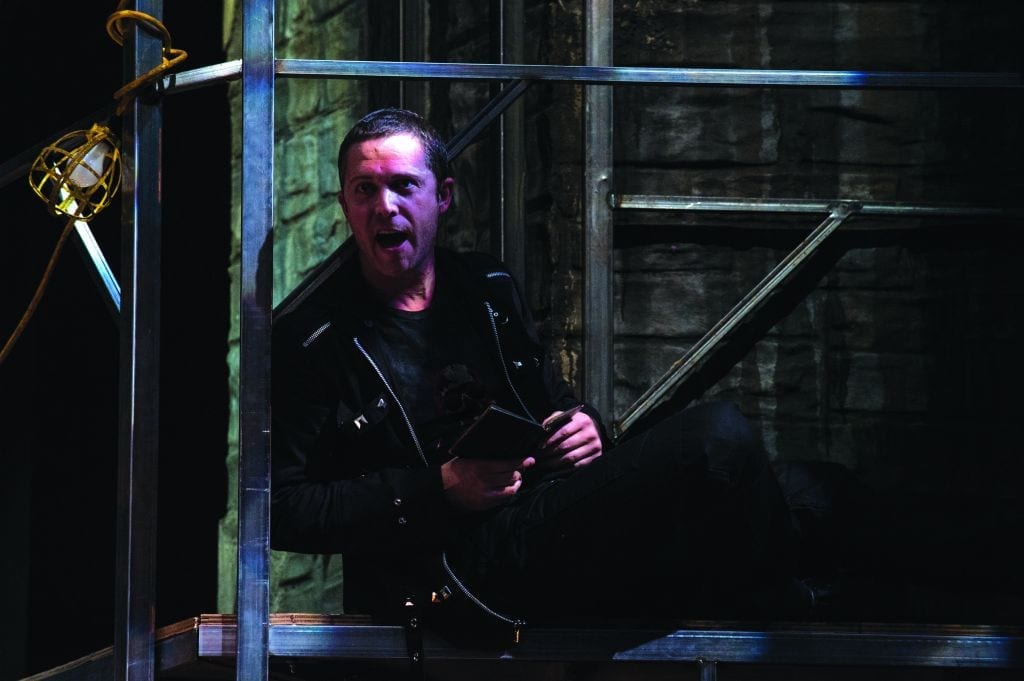

The most distinctive aspect of this production of Shakespeare‘s classic play is Danforth Comins in the title role. Most Hamlets I’ve seen are sullen, introspective men—a portrayal that I’ve always accepted. Comins, however, gave the audience a wild-eyed, energetic Hamlet. After I adjusted to a new type of Hamlet, I found that Comins’s interpretation was fascinating and faithful to the text. Comins’s natural vigor made many familiar scenes (such as his first confrontation with Ophelia) livelier than I had ever seen before. But Comins isn’t a manic Hamlet; the actor still found appropriate moments of contemplation that made the famous soliloquies—especially the “What a piece of work is man” monologue in Act II—as profound as they were 400 years ago.

Sara J. Griffin and Kymberly Mellen were riveting in their performances as the only two female characters in the play, Ophelia and Gertrude, respectively. Griffin created a vulnerable, tender Ophelia. It was clear why Hamlet’s rejection of Ophelia wounded her so deeply and made her go insane. Mellen, meanwhile, helped me see Gertrude, for the first time, as a character torn between two members of her family, both of whom she deeply loves. Gertrude’s transformation after The Murder of Gonzago (the play within the play performed during Act III by a visiting acting troupe) from powerful regent to a hopeless mess of a human being was completely believable and innovative. To cap it off, Mellen’s choices for her character’s development made Gertrude’s death a natural consequence of her personality changes, which I had never seen before.

Ben Jacoby‘s portrayal of Laertes reminded me why the character is my favorite supporting role in the Shakespeare canon. Jacoby showed, during his scene with Claudius, that Laertes’s desire for Hamlet’s death was a personal thirst for vengeance—a fact sometimes ignored by actors playing the role. Jacoby used Laertes’s loss of his entire family (due to the actions of Hamlet) as a catalyst for a visceral bloodthirst towards Hamlet that held me enthralled. Moreover, the sword fight between Jacoby and Comins in the final scene of the play was, by far, the most exhilarating sword fight I’ve ever seen live on stage. I applaud the fight director, Christopher DuVal, for finishing the play with a fight that was much more interesting and exciting than many of the fights that I see on television or in movies.

Other male actors were also impressive. Max Robinson played Polonius as a doting and loving father to his two children. As played by Robinson, Polonius’s scenes with his children, such as when he is giving advice in Act I to the departing Laertes (including the nugget of wisdom, “To thine own self be true”), is genuinely touching. Also, Phil Hubbard as Claudius was interesting, as the character used different tactics to try to keep a hold on his newly obtained power.

Barricelli’s directing and concept, though, is the essential ingredient to all of these actors’ successful performances. In my view, the directing in a production of Hamlet is satisfactory if it is never completely clear whether Hamlet is truly mad, or whether he is merely feigning madness (a debate that the play’s audience has been having for centuries). Barricelli succeeded in maintaining this ambiguity. But Barricelli’s artistic decisions are what raises this production from being merely satisfactory to being truly exemplary. Barricelli brilliantly added fascinating stage business (such as when Hamlet is explaining where the deceased Polonius is) that doesn’t just give the actors something to do while they speak. Rather, the actions highlight the text, expand its meaning, and develop character traits within the characters. Barricelli also creates vivid stage pictures (like Ophelia’s funeral in Act V) that I’ll remember for years to come.

Assisting Barricelli in the visual beauty of this production is his excellent design team. David Kay Mickelsen‘s costumes were modern, 21st century sharply tailored suits and gracefully designed dresses, which all emphasized the opulence of the court and the characters’ political, social, and economic power that was put at risk by Hamlet’s actions. Contrasting with Mickelsen’s gorgeous costumes was the set designed by Jo Winiarski. The decrepit and decaying appearance of the set, juxtaposed with the fine clothes the characters were wearing, served as a constant and powerful non-verbal message about how the people who ran the court—especially Claudius and Gertrude—had skewed priorities.

In Act III of Hamlet, Claudius says, “Madness in great ones must not unwatched go.” Out of the 22 productions at the Utah Shakespeare Festival that I’ve seen in the past three seasons, this year’s Hamlet is one of “the great ones,” and it “must not unwatched go.” The play is a must-see, whether you’re a longtime fan of the script, or seeing it for the first time.

[box type=”shadow”]The Utah Shakespeare Festival production of Hamlet plays at various days and times through October 27 at the Randall L. Jones Theatre on the campus of Southern Utah University. Tickets are $28-64. For more information, visit www.bard.org.[/box]