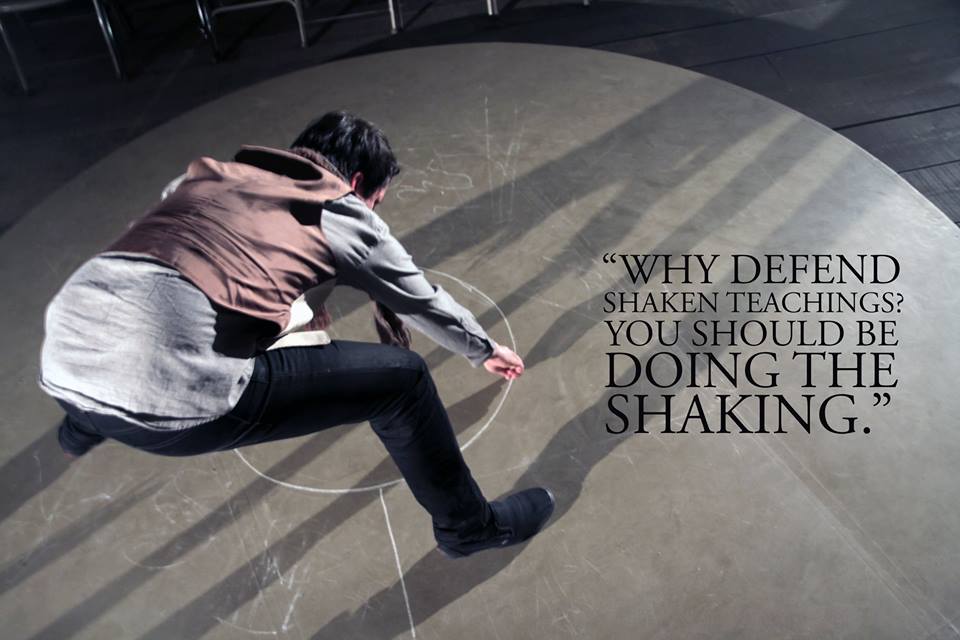

PROVO — In a dimly lit room above the Provo Castle Amphitheater, Galileo’s cast of ten stepped onto a raised, round stage, nine holding hands in a circle around Galileo, singing a melancholic melody, “In the year sixteen hundred and nine, science’s light began to shine… Galileo Galilei set out to prove the sun is still, the earth is on the move.” These words remained projected on a side wall after they stopped singing and walked out, leaving only Galileo (played by Barrett Ogden) crouched on the stage, drawing astronomical figures on the ground in chalk.

From the outset, Galileo’s intense scientific curiosity was instantly palpable, and his enthusiasm for sharing his discoveries was contagious as he took a young neighbor (Shawn Saunders) under wing in the first scene. Galileo follows the titular character from his first encounter with the telescope through his most famous discoveries and the conflict those discoveries create with the Catholic Church.

Bertolt Brecht’s script is filled with memorable, poetic language, tying together captivating scenes with songs and verses of common themes. Davey Morrison Dillard’s tight direction and mastery of aesthetics made the entire play a feast for the senses. The use of language to express the political and human conflict Galileo faced was exemplified in a scene where Galileo and Sagredo (Addison Radle) take turns at the telescope. Galileo exclaims, “Stop standing there like a stuffed dummy when the truth has been found.” And Sagredo aptly replies, “I’m not standing like a stuffed dummy; I’m trembling with fear that it may be the truth.”

While the play obviously lauds scientific discovery, it does not beatify Galileo or demonize the Church. Instead, even as Barrett Ogden’s Galileo exuded an obvious passion for his work, but he didn’t define his character by scientific discovery to the exclusion of all else. Galileo alternately motivated by money, science, self-preservation, love of family, etc., and all of these aspects of the character felt organic and real. On the opposite side of the spectrum, the views and concerns of the Church were shown from many different perspectives, most of which are not blindly hostile toward scientific discovery. In the scene between Galileo and a devout monk who also had an interest in physics (Jamie McKinney), I was moved by McKinney’s deep conviction and portrayal of spiritual conflict, and by the way Ogden’s patient Galileo was willing to listen and explain his views in the face of criticism.

While the play obviously lauds scientific discovery, it does not beatify Galileo or demonize the Church. Instead, even as Barrett Ogden’s Galileo exuded an obvious passion for his work, but he didn’t define his character by scientific discovery to the exclusion of all else. Galileo alternately motivated by money, science, self-preservation, love of family, etc., and all of these aspects of the character felt organic and real. On the opposite side of the spectrum, the views and concerns of the Church were shown from many different perspectives, most of which are not blindly hostile toward scientific discovery. In the scene between Galileo and a devout monk who also had an interest in physics (Jamie McKinney), I was moved by McKinney’s deep conviction and portrayal of spiritual conflict, and by the way Ogden’s patient Galileo was willing to listen and explain his views in the face of criticism.

In a conversation between the Pope (Jessamyn Svensson) and the Inquisitor (Alex Ungerman), both actors made it easy to feel some compassion for the Church’s tricky position. Amid a polarized political and religious climate they felt obligated to protect against the controversial messages of Galileo’s scientific discovery. Considering which side of history they wound up on, modern people often demonize the Church’s actions during this epoch, but Svensson and Ungerman made these characters feel human, and therefore strangely sympathetic.

In a conversation between the Pope (Jessamyn Svensson) and the Inquisitor (Alex Ungerman), both actors made it easy to feel some compassion for the Church’s tricky position. Amid a polarized political and religious climate they felt obligated to protect against the controversial messages of Galileo’s scientific discovery. Considering which side of history they wound up on, modern people often demonize the Church’s actions during this epoch, but Svensson and Ungerman made these characters feel human, and therefore strangely sympathetic.

Musical interludes were frequently used for transition and exposition. Noah Kershisnik’s guitar and vocal talent would have been impressive already, but when he and Emily Dabczynski (who also played Galileo’s daughter) added audience interaction to the mix, his musical numbers were an absolute pleasure that helped the show move forward briskly and cleansed the emotional palate between scenes.

The actors each dressed in plain black shirts and pants. Changing costume pieces, including masks, were worn on top of the generic getup to signify different characters. The costumes were varied enough that I had no trouble identifying each of the different roles, even though most of the actors were playing two or more roles.

The actors each dressed in plain black shirts and pants. Changing costume pieces, including masks, were worn on top of the generic getup to signify different characters. The costumes were varied enough that I had no trouble identifying each of the different roles, even though most of the actors were playing two or more roles.

The raised stage was bare, as a default, with sundry tables, chairs, books, and candles set about the room, next to and beside the audience seating on three sides of the room. Transitions were fluid, with cast entering and exiting from doors on all sides, often carrying furniture and other props onstage with them even as they spoke their lines.

The play was fast-paced and cohesive. The cast’s talent was apparent even in short scenes involving minor characters—such as the exchange between Shawn Saunders, as Andrea, and Jessica Myer, as the peasant—and it was easy to see how all the pieces fit into the play’s message. Brecht’s script is thought-provoking without forcing one interpretation, and Dillard’s production leaves audience members with something to think about from every scene. I relished every minute of this very polished production, and I can’t wait to see what project Dillard will take on next.

[box type=”shadow”]Galileo plays every Friday, Saturday, and Monday through September 27 at the Castle Amphitheater (1300 E. Center Street, Provo) at 7:30 PM. Tickets are $10. For more information, visit www.facebook.com/events/840612865951064.[/box]