SALT LAKE CITY — The new rock musical A Wall Apart at The Grand Theatre tells the story of one family’s experience of living through the nearly thirty-year division of their beloved city by the Berlin Wall. While the history of the wall is ripe with fascinating human stories of tragedy and heroism, and while the wall carries obvious resonance in our political moment, this musical is lackluster. Despite the best efforts of all those involved, it stuck me as an overly sentimental plot framed by mostly forgettable power ballads.

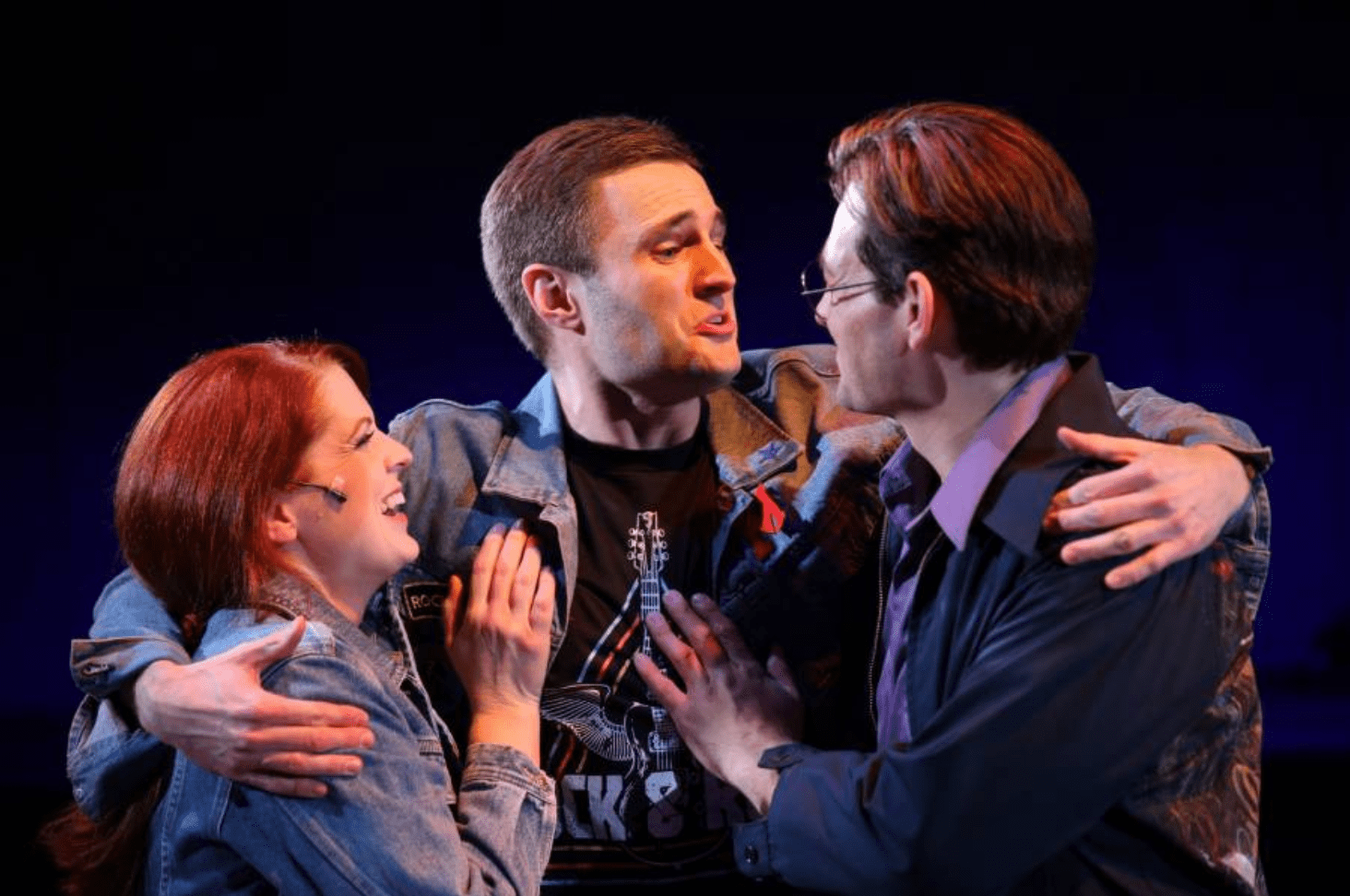

As the story begins, the audience meets three brothers who, notwithstanding a childhood of severe loss and trauma, share a deep love each other and their home city, Berlin. It’s 1961, and their world is still being rebuilt after the destruction and suffering of World War II. The city is divided physically and politically between eastern (Soviet) and western (American) control, as are the brothers. The youngest, Micky, is the front man of a rock and roll band with great songs and big dreams. Mickey (played by Holden Smith) and his fiancée Suzanne (played by Ashlyn Brooke Anderson) are shimmying their way into a bright future. Mickey is pitted against his eldest brother, Hans (played by Darren Ritchie), a rising member of the Soviet police force that is increasingly restricting the freedoms of the city’s eastern citizens. The story’s protagonist, Kurt, is played with passion by Michael Scott Johnson. Kurt feels unsure of himself, pulled between the opposing ambitions of his brothers, and the emergence of a sudden romance with Esther (played by Ginger Bess) who has entered his life in a moment when nothing else seems to make sense.

With romance and political upheaval creating high stakes, these characters are provided a fascinating context for their action, which is why my own boredom with the progression of the story surprised me. This feeling of tedium is the result of the saccharine behavior demonstrated by the characters—not to be confused with the excellent emotional expression of the actors—at each dramatic turn of events. These characters, whose lives are being torn apart by historical events, seem to take it all in stride. There are no traumas they cannot face, no bitter words that a, “but I love you” cannot heal. There are many sorrowful speeches followed by increased determination to make things right. The characters are overly simple in their desire to endure and be good. There is no grit in their humanity, and the abstract complications of politics are our only villain.

With romance and political upheaval creating high stakes, these characters are provided a fascinating context for their action, which is why my own boredom with the progression of the story surprised me. This feeling of tedium is the result of the saccharine behavior demonstrated by the characters—not to be confused with the excellent emotional expression of the actors—at each dramatic turn of events. These characters, whose lives are being torn apart by historical events, seem to take it all in stride. There are no traumas they cannot face, no bitter words that a, “but I love you” cannot heal. There are many sorrowful speeches followed by increased determination to make things right. The characters are overly simple in their desire to endure and be good. There is no grit in their humanity, and the abstract complications of politics are our only villain.

The music and lyrics written by Graham Russell do not provide a helpful structure for the production. Action is stuck on repeat: a character is introduced to a conflict, the internal emotional conflict is expressed via ballad, repeat. The songs fail to move conflicts or characters forward and somehow always end with their titles, like “We’re Having a Baby” or “Heart Don’t Break” being repeated at least four times. There are a few compelling musical variants in the song list. The touching lullaby “Forlorn Fraulein” is a lovely moment among the fraught family members. It is shared by the story’s gentle comic relief, Tante (played tenderly by Mary Fanning Driggs). The musical high point came early in the show with Smith’s rendition of the catchy rock jive “Shake It.”

The music and lyrics written by Graham Russell do not provide a helpful structure for the production. Action is stuck on repeat: a character is introduced to a conflict, the internal emotional conflict is expressed via ballad, repeat. The songs fail to move conflicts or characters forward and somehow always end with their titles, like “We’re Having a Baby” or “Heart Don’t Break” being repeated at least four times. There are a few compelling musical variants in the song list. The touching lullaby “Forlorn Fraulein” is a lovely moment among the fraught family members. It is shared by the story’s gentle comic relief, Tante (played tenderly by Mary Fanning Driggs). The musical high point came early in the show with Smith’s rendition of the catchy rock jive “Shake It.”

In contrast to the score, it is Sam Goldstein and Craig Clyde’s collaboration of story and book that provides for the actors and action to shine. Moments of strong dialogue are highlighted by the actor’s compelling vocal and physical expression. Ritchie is particularly well placed as the duty-bound eldest brother who, in spite of an unflappable exterior, wrestles with doubts and personal convictions.

The production is billed as “Backstage at the Grand,” and the audience is fittingly divided on either side of the stage. The whole set and audience sit on the stage of the elegant Grand, creating an intimate, if close kneed environment. Director/choreographer Keith Andrews has made wonderful use of David Goldstein’s intricate set and lighting design. The work comes together beautifully with precise movement and emotion in the Act I closing number “Too Late to Dream.” The onstage rock combo, headed by guitarist Jeff Alleman, also adds a special flare throughout the performance. It is obvious that the production team and actors collaborated closely to make the most of this work that can’t seem to rise to its own promise.

[box]A Wall Apart plays at The Grand Theatre (1575 South State Street, Salt Lake City), Wednesdays through Saturdays at 7:30 PM and Saturdays at 2 PM through September 7. Tickets are $12-23. For more information, visit grandtheatrecompany.com/.[/box]