SALT LAKE CITY — In 1921, Italian playwright Luigi Pirandello premiered Six Characters in Search of an Author. It was a curious piece of theatre unlike anything his audiences were familiar with. The initial performance was met with great controversy, and the author himself forced to exit the theatre through a side-door to prevent those in opposition to his work. But what made this piece so incredibly provocative to audiences? An illogical narrative progression, combined with blurred lines of reality and theatrical makes for a rather provoking story, one that probes at the nature of “art imitating life” and reasons for performance. Now in 2014 Westminster Theater Society produces this piece, and the result is interest.

First, that I did not find this play entertaining. I did not enter the theater and find myself dazzled by any spectacle, or grow rapidly engaged in the story unfolding on stage. There wasn’t a sense of leisurely viewing to be had in this play, nor does the script really allow for as much. Rather, a philosophical debate occurs between the characters that makes the production feel more akin to rhetorical reasoning than anything a theater-goer might expect to see as “performance.” And while this absolutely seems the intent of Pirandello’s script (translation by Edward Storer), I found myself faced with a fairly blase interpretation of this famous script. No frills or interpretive lens heightened this piece. As a reference for students of theater seeking to study the genre of absurdist metatheatrical, however, it’s a prime example.

I appreciated that there was no clear beginning to this piece. The actors sauntered on in leisurely pace, speaking as if they were setting up for rehearsal and attending to the typical tasks of prepping to run a scene. When scripted lines began, an oddly artificial speech cadence settled over the conversations. Whether this can be blamed on a stylistically dated script, a director’s choice to have the actors “act,” or mismanagement with the words, I don’t know. All the same, there was a very keen awareness that this was a play. Stage hands appear onstage at times, set pieces are moved in and off from backstage, and the overarching feel of meta-theatricality permeates the performance.

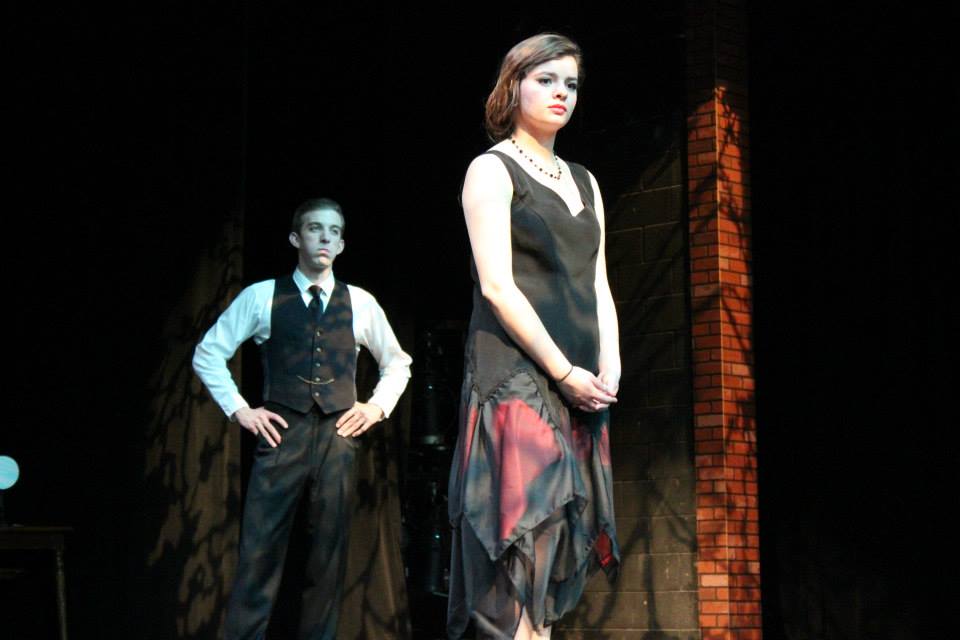

Lighting (designed by Blake Delwisch) remained fairly neutral, though when the Six Characters played out their dramas, the stage lighting became noticeably theatrical—and really, the effect was quite beautiful. The choice of color and gobos worked well, and consequentially the lighting heightened the sense of performance. Costumes (designed by Allisyn Thompson) were executed well and helped to delineate the mode of character background. The stark black of the Six’s costumes and a fairly neutral space allowed for the performance to focus on the philosophical debate. The set design and set pieces brought in to recreate the Six Characters’ collective story were beautiful, heightening the notion of “performance.” Everything associated with theatrical performance held theatrical value. Costumes were costumes, lights were lights, etc.

Lighting (designed by Blake Delwisch) remained fairly neutral, though when the Six Characters played out their dramas, the stage lighting became noticeably theatrical—and really, the effect was quite beautiful. The choice of color and gobos worked well, and consequentially the lighting heightened the sense of performance. Costumes (designed by Allisyn Thompson) were executed well and helped to delineate the mode of character background. The stark black of the Six’s costumes and a fairly neutral space allowed for the performance to focus on the philosophical debate. The set design and set pieces brought in to recreate the Six Characters’ collective story were beautiful, heightening the notion of “performance.” Everything associated with theatrical performance held theatrical value. Costumes were costumes, lights were lights, etc.

The performances themselves varied. I appreciated the level of intensity Father (Michael Calacino) delivered in trying to persuade Director to pen the story of their lives. With a weight bit of the script to memorize, I thought Calacino did a solid job of line delivery because it still felt like just that: line delivery. Amanda Corbett as Step-Daughter brought a fun flavor to the stage, and though she was charming, I grew tired of the repetitive nature of her argument with Director and Father. The excitement of having the Six Characters introduced to the stage quickly dwindled as any narrative action quickly fell into the same moral debate of illusion versus reality. Moments of action—admittedly sparse—ensured that my attention never wandered from of the play, though my mind was more at work processing the arguments made versus simply sitting back and enjoying the show.

A major barrier to my enjoyment of the play was the pace at which it dragged on. I found myself anxiously awaiting the Characters’ story being acted out and revealed to full effect on stage, and I grew frustrated every time the dialogue pulled out to return to more discussion on the moral implications of acting out another’s story. The catharsis of performance—that living of another’s life through narrative structure—was absent completely. That being said, this performance did evoke strong emotion. As a performer myself, I was struck by the curiosity of argument presented. There’s always a personal reality that exists in performance, a story that must be told. And how do we, as performers, neglect to realize that fruition of story cannot be realized simply because we are injecting ourselves into the role? Or that the scene cannot be recreated with exactitude, simply because memory of scenes can never be perfect? There’s a lie that unfolds in performance, the simple medium of art somehow distorting the truth and disserving those that experienced the truth itself. Art becomes a game, in stark opposition to the sole reality experienced only by those living the truth expressed on stage.

Very metatheatrical indeed.

Overall, Six Characters in Search of an Author was slow, focused more on the necessity getting to the crux of philosophical truth and removed from anything that the typical theater-goer might expect to see. I left the theater disgruntled. Yet the theories discussed in the show led to an interesting discussion with my guest on the ride home, focusing namely on the integrity of performing another’s story. We discussed whether directors play God, or if acting is doing a service to the community at large, or if pretending to be another is a deceit and unholy mockery of the original character’s truth. No, I wasn’t entertained. But I was afforded a very interesting conversation and introspective look via this performance. And for that, I was grateful to the Westminster Theatre Society.

[box type=”shadow”]The Westminster Theater Society production of Six Characters in Search of an Author played May 22-24 at the Lees Courage Theatre on the campus of Westminster College. For more information about future productions, visit