SALT LAKE CITY — Lyman Felt is a fellow who is quite proud of the fact that he lives his life to the fullest. He is robustly healthy in his middle age; he is wealthy and successful in his work; and he appreciates women. He appreciates them so much he has two wives. Now you must understand—Lyman isn’t a polygamist. He’s a bigamist. After proposing to his lover, Lyman neglected divorcing—or even telling—his first wife and simply married his second. Just like that.

Both wives go blissfully through life for the next nine years, each unaware of the other until they meet in a hospital waiting room following Lyman’s potentially un-accidental drive down an icy mountain road.

Lyman Felt is pretty much a bastard, and he admits to it. I spent a lot of my Friday evening in the Dumke Black Box wanting to give him a nice left hook. He is a selfish, callow, and dirty-minded individual. Playwright Arthur Miller manages to make Lyman interesting, if not necessarily likable, despite his faults. There is a fine line that must be walked when telling a story as complicated and potentially controversial as Lyman’s—it can be poignant, or it can be ridiculous. Unfortunately the Westminster Players’ current production of The Ride Down Mt. Morgan leans toward the latter.

The production, directed by Pinnacle Acting Company’s Jared Larkin, is simple and sparse, for the most part moving fluidly between past and present. There is a very cool sequence at the top of the show that gives the impression of Lyman’s Porsche careening along an icy road—from that point, you know something is going to break, which is a great place to start a play. However, it didn’t take long to lose that momentum.

Stylistically the play is a lot to handle. Miller breaks Lyman’s story into a series of vignettes: present day moments of Lyman in his hospital bed are interspersed with memories of both wives. One of the few moments that includes both wives on stage simultaneously is a moment of surrealism that isn’t quite earned. The balance is tricky, and I don’t know if there is enough experience in this youthful, passionate company to quite carry it off. Key to that balance is the idea of belief. I never really believed what was happening on stage—not enough to feel for Lyman, or even for his deceived wives. One part of this was that there wasn’t really any attempt to make any of the cast appear—or even seem—older. Lyman Felt is written to be a middle-aged New Yorker. He is played here, I can’t doubt energetically, by Paul Burgess, a spry twenty-something. While it’s obvious that Burgess has thrown himself into this role, there are vocal and physical tells that make it very difficult to buy his Lyman. It seems to be a stylistic choice to not use old age make-up in this production; it’s far too broad a generalization to claim that the show doesn’t work because Lyman’s hair isn’t gray, at the same time that I think it can only help. As things were, I was taken out of the action multiple times because I couldn’t suspend my disbelief.

Miller’s plays are packed with dense language that isn’t easy for even experienced actors to navigate. The dialogue in Mt. Morgan in particular ranges from lyrical to erotic to foul, but mostly sounds clunky here; the lines are recited rather than inhabited. The acting got shrill and indulgent in places, with many of the cast choosing volume and tears over intensity and connection.

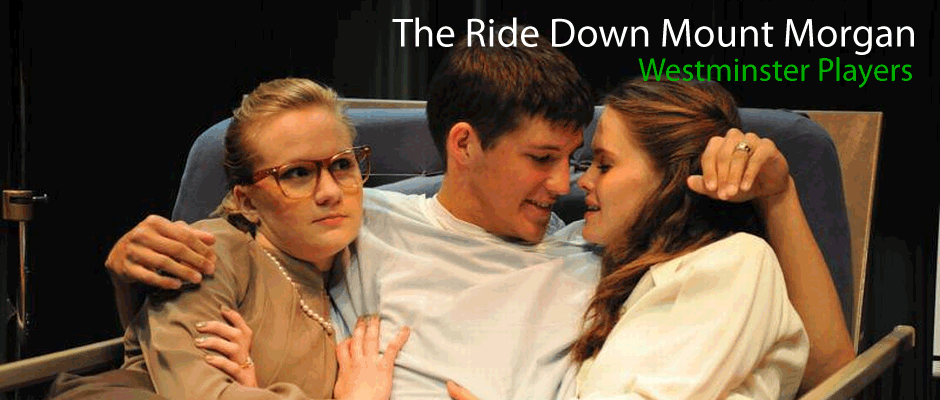

Burgess has fun nailing Lyman’s less appealing qualities, but it would have been nice to see some other layers to him. Lyman’s wives—timid, mousy Theo (Mandi Titcomb) and brash, expensive Leah (Sahara Hayes)—seem to be convenient polar opposites in personality, yet Lyman is still Lyman with either or both of them. I think Larkin could have plumbed deeper with his cast to find more of what was going on in these three separate yet intertwining lives.

I can see the value in revisiting this play, one of Miller’s last, first written and produced in the early 1990’s. However, the choice to produce the play as the university level seems strange, especially considering the ages and life experience written into the characters. The Westminster Players should be commended for embracing the challenge, even if the result falls a little short.

[box type=”shadow”]The Ride Down Mt. Morgan plays October 13-15 at 7:30 in the Dumke Black Box Theatre on the campus of Westminster College. Tickets are $10. For more information, click here.[/box]