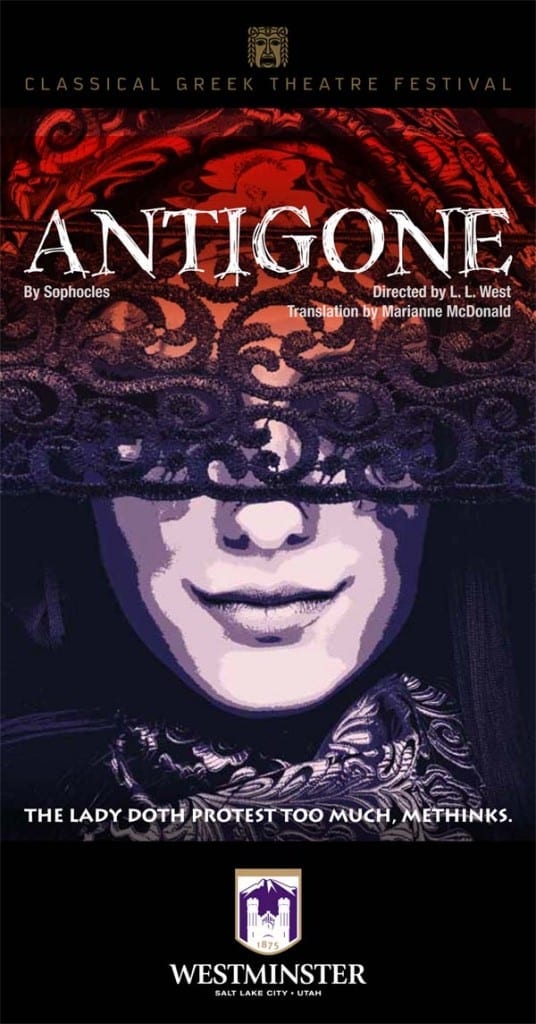

SALT LAKE CITY — The most important news story of 2011 was, unquestionably, the Arab Spring. Beginning in late 2010 in Tunisia, a fervor of revolution spread through many Arab countries. Massive protests were organized, despots were overthrown, and a new wave of uncertainty spread throughout North Africa and the Middle East. The world is still dealing with the results of these protests, which led to bloody civil wars in Libya and Syria. This backdrop of turmoil and violence serves as the setting for a compelling production of Antigone, which is this year’s production from the Classical Greek Theatre Festival.

Written by Sophocles in the 5th century B.C. (and translated by Marianne McDonald), Antigone is a play in which the title character must choose between doing what is right and following the law. Antigone’s conscience urges her to bury her treasonous brother, Polyneices, in order to assure him a peaceful afterlife and to avoid shame for the surviving family. But the new ruler, Creon, has decreed that the body is to remain in the open air as a consequence of the turmoil that Polyneices unleashed on the city.

L. L. West’s direction of this production was superb. Normally I am ambivalent about changing the setting and time period of classic scripts. Sometimes the new setting works, and sometimes it doesn’t. But West’s decision to set Antigone in present-day Syria was an excellent choice that helped me to commit myself fully to watching the story. Rather than merely dressing up the actors in modern clothes (as is usually done in such productions), West committed fully to the new setting by having the Greek chorus act as a variety of slices of modern society, including the media, a mob, social media addicts, and more. West’s choices for the chorus succeeded greatly in making this convention of ancient Greek theatre seem less foreign than it usually does. Almost all of the non-chorus characters all had clear, recognizable analogs in 21st century society, such as the Gaddafi-like Creon and the efficient bureaucrat who was Creon’s advisor. The only scene that I felt didn’t work in the new setting was with the soothsayer, Teiresia (played by Holly Fowers). I don’t feel like this is any great detraction from the overall show, though. Anyone attending this play would understand that it was written almost 2,500 years ago, and it would be unrealistic for an audience member to expect that every scene and character would transfer smoothly to a different time and culture.

Jared Thomson was a superb Creon, the rigid, vindictive ruler whose stubbornness and hubris leads to the tragic conclusion of the play. Thomson was an excellent performer in a long line of theatrical tyrants. His portrayal reminded me (positively) of Hamlet‘s instruction to the players that they should “out-Herod Herod.” Thomson was never cartoonish in his villainy, though. Rather, his Creon seemed like a man used to getting his own way and determined not to give into a girl because it would look like a sign of weakness. Although clearly self-interested, Thomson’s Creon also seemed motivated by preventing civil unrest, which would result if another rival believed him to be a weak ruler and tried to break Creon of his tenuous grasp on power.

Annie Brings played Antigone bravely, but not overbearingly. As played by Brings, Antigone simply has a filial duty to fulfill. She is willing to suffer the wrath of an earthly power if it means satisfying the gods. Antigone’s firm belief in what was right empowered her, and made Brings’s performance quite interesting. I also thought that Wyatt McNeill excelled in making his character of Creon’s advisor an interesting person to watch, instead of just a flat character who does the ruler’s bidding (like so many Shakespearean messengers). McNeil’s best scene was when he was questioning Creon’s orders concerning Polyneices’s body.

Moreover, the women of the chorus—especially Fowers, Vicki Pugmire, and Tamara Howell—were essential in the successful execution of the director’s concept. Their facial expressions in every group chorus scene were entrancing and made the chorus’s lines more than mere recitations (as I’ve seen before in ancient Greek plays). This was especially true when the chorus acted as the media and in the last third of the play when the tragic ending comes crashing towards the characters. The only performance in the play that I was not satisfied with was from Conor Thompson, who played the guard. Thompson tried to play the role comedically. However, not only did he elicit very few laughs from the audience, but the choice of being humorous didn’t make sense. I thought that when he was smart-mouthed to Creon, it was insubordinate and not funny. As a tyrant, Creon should have quickly (and violently) put such a disrespectful soldier in his place. But because Creon did not react that way, the choice of making the guard funny was puzzling. It never worked for me. I don’t know if this was Thompson’s fault; perhaps this was merely the direction he received from West.

The costumes are probably the most interesting technical element of the play. Philip Lowe constantly reminded me of the Middle East setting of the production through use of head scarves, jackets, and other distinctive pieces of clothing. I also appreciated the sound design from Mikal Troy Klee. Klee always seemed to have the perfect music selections to fit the mood and setting of the play. However, I believe that the choice to use microphones was disappointing because they frequently popped and had other problems. Because I have seen other theatre companies perform in larger, more open outdoor spaces successfully without microphones, I feel like the microphones were unnecessary. I’m willing to admit that I am not familiar with all of the spaces that this company will perform in, so perhaps they will need the microphones in other venues.

Last year, I called the Classical Greek Theatre Festival’s production of Iphigenia in Tauris “educational, though not entertaining.” I recommended that audiences see that play mostly because it is rarely produced and ancient Greek theatre is an important part of our theatrical heritage. This year’s Antigone is also educational and important, but it’s much more than that. Antigone is interesting, relevant, and entertaining. And at just under 90 minutes, it’s an excellent production to use to introduce someone to ancient Greek tragedies. I especially recommend arriving 30 minutes early to hear the excellent lecture from artistic director and dramaturg James T. Svendsen.

[box type=”shadow”]The Classical Greek Theatre Festival’s touring production of Antigone plays at Red Butte Garden Amphitheater (300 Wakara Way, Salt Lake City) at 9 AM on September 22-23 and 29-30. Other performances at various places in Utah and Colorado will occur through October 6. Tickets prices vary. For more information and exact performance dates and locations, visit www.westminstercollege.edu/greek_theatre.[/box]