PROVO — Walking into the Hive Collaborative, I was immediately struck by the set for Lost Works. Having been to the venue a few months ago for Klouns’s delightful, near-incredible production of Icarus, I was amazed to see the space transformed into an honest-to-goodness 17th century inn.

The playbill does not mention who was responsible for this wonder of carpentry, but it was truly an impressive feat. On one end of the stage, a legit looking bar — and on the other side a giant fireplace. The set’s detail went all the way to the ceiling, too—instead of simply ending at the top of the walls, the space above them was furnished with spires of lathed wood, which complemented the inn set perfectly. The set was also dominated by three large televisions, used for additional set dressing.

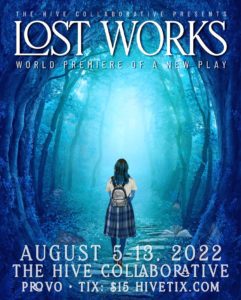

Lost Works is a new play by writer/director Dennis Agle Jr. that explores a group of Shakespearean-like characters who gain self awareness. Like Toy Story characters grappling with their existence, they begin to wonder: Who are they? Why do they only exist when they are on stage? And what lies beyond it? It is a premise full of possibilities.

The cast is led by Alex Russon as Geoffrey, a simple farm boy — er…houseboy—in full “As you wish,” “he’s simple but he’s cute,” Wesley-eque hearthrobbiness. Russon’s hair was so dreamy, it was practically its own character. More importantly, Russon gave a sweetly sincere performance and likely caused a few hearts in the audience to melt.

The show is aided enormously by two mature actors, Dane Allred as the Earl of Bedford and Geoffrey Means as Rowland. Allred’s experience as a veteran of stage and as a university public speaking professor shined through his comfort with the Elizabethan-esque dialogue. Both actors brought loads of humor to the show. (Means’s subtle, defeated look when a character made an ageist comment about him was golden.)

The show is aided enormously by two mature actors, Dane Allred as the Earl of Bedford and Geoffrey Means as Rowland. Allred’s experience as a veteran of stage and as a university public speaking professor shined through his comfort with the Elizabethan-esque dialogue. Both actors brought loads of humor to the show. (Means’s subtle, defeated look when a character made an ageist comment about him was golden.)

The play finds some amusing and creative ways of the characters discovering that they are acting out a Shakespeare-like play, like when the characters realize they are speaking in iambic pentameter and their play features cross-dressing (a classic Shakespeare plot device). The play-within-a-play is called All In Good Time. It is not a real incomplete Shakespeare play. However, I could not tell if All in Good Time was supposed to come off as a passable Shakespeare play, or a poor one. Agle’s prose is certainly no Shakespeare. Perhaps Lost Works could benefit from moving the play out of the middle ground and being more obviously bad, thus reducing the dissonance in the audience’s mind between the quality of real Shakespeare and what is onstage. This stronger distinction could also help the actors. While the two older actors were comfortable with the language, the words did not sound so natural on the tongues of the younger actors. I struggled with Teresa Gashler’s delivery, which was showy and unnatural. People in the 17th century still acted and talked like real people, even if they spoke differently.

Lost Works can be broken up into three parts: 1) Shakespeare-like characters gain self-awareness and decide to leave their world 2) They arrive in modern England and travel to Stratford-upon Avon to find Shakespeare 3) The relationship between the characters and the narrator is revealed for a bittersweet ending. Thematically speaking, parts 1 and 3 are solid. The concept is delightful, the comedy in Act 1 kept the audience laughing and the conclusion was satisfying.

Lost Works can be broken up into three parts: 1) Shakespeare-like characters gain self-awareness and decide to leave their world 2) They arrive in modern England and travel to Stratford-upon Avon to find Shakespeare 3) The relationship between the characters and the narrator is revealed for a bittersweet ending. Thematically speaking, parts 1 and 3 are solid. The concept is delightful, the comedy in Act 1 kept the audience laughing and the conclusion was satisfying.

The second part has room for improvement. While the idea of Shakespearean characters trying to find the Bard is brim with promise, as soon as they arrived in England, the show seemed to deflate. The laughs dwindled, and the plot became repetitive as they faced a series of inconsequential obstacles, including one ticket window after another. If Shakespearean characters did arrive in the modern day (like Giselle in Enchanted), there are so many more compelling, interesting, and entertaining situations they could experience than gaining a seemingly endless series of tickets. Agle may consider putting this section on the shelf and developing a new middle—one that also develops the romances.

Another reason the second act dragged was that the best character disappeared: The Blue Girl, played with schoolgirl bubbliness by Sophie Rose. Her fawning over Geoffrey was the best part of Act 1, and the reasons why she cannot interact in the real world do not seem clear or worth sacrificing her character. Why can the products of her imagination (i.e., the Shakespeare characters) exist but her imagination itself (i.e., Blue Girl) cannot?

Romance is another area of potential improvement. Ending with a double wedding is certainly Shakespearean, but the twin romances had zero development beyond Geoffrey dropping his buckets at the sight of Gillian. And poor Valet! Why did the humble-but-growing, scene stealing, strong-silent type — appealingly portrayed by Jacob Baird — end up with the catty Celia? She does not deserve him (and vice versa).

Part of the magic of Lost Works is its mystery. And its conclusion when all is revealed is sweet and heartwarming. Still, my niece and I did feel a little, ahem, “lost” during the show. The director’s notes may be an area for grounding and preparing the audience about what they will see. Perhaps some information about the play-within-a-play or how the narrator interacts with the characters could help. After all, Shakespeare productions often come with pages of plot explanation That could help Lost Works too.

One quick thing from a technical perspective (the technical director was Davis Agle): if the fake Shakespeare (can I call him Fakespeare?) in Stratford was a hologram, why did he look and move like an animatronic puppet? Isn’t the point of holograms — whether Tupac or ABBA — to look like real humans? Pick a lane, Fakespeare!

Lost Works is generally family friendly. While there was a lot of standing and talking, my 10-year old niece enjoyed it. There are a couple off-putting jokes, including women comparing the size of their breasts in Act 1, and Geoffrey telling a woman he’s going to give her a night she’ll never forget in Act 2. But otherwise, the show is appropriate for all ages.

Overall, Lost Works is a sweet, good-hearted show with an intriguing premise and satisfying conclusion. It features some good performances and plenty of laughs. While there is room for improvement in the script and other areas, it is a commendable show and deserves consideration.

[box]Lost Works plays nightly (except Sundays and Tuesdays) at 7:30 PM and Saturdays at 2 PM through August 13 at The Hive Collaborative (290 West 600 South, Provo). Tickets are $15. For more information, visit thehivecollaborative.com.[/box]