LOGAN — Leave it to Arthur Laurents, Leonard Bernstein, and Stephen Sondheim to take a challenging story like Romeo and Juliet and drop it into the West Side of New York, thus adding new difficult dynamics of economics, immigration, race, and crazy difficult music. The Utah Festival Opera Company picked up the gauntlet and produced an electrifying West Side Story that dazzled with amazing vocals, great choreography, solid dancing, stunning visuals, and poignant acting.

The opening number, the famous, “Jet Song,” started strong with the classic flavor of the 1961 movie. Director and choreographer George Pinney designed a variety of movements that had great contrast between the slow and the fast, the big and the small. The energy kept building in intensity throughout the song. The few dancing flubs didn’t effect the energy of the show, and they didn’t over use the snap. In practically every case, the group dancing was stunning. The choreography in the number, “Cool,” had so much tension and release that it was particularly satisfying, and the girls in that dance scene were utilized wonderfully. The number had a lot of “pow!”

The performance of, “Gee, Officer Krupke,” was tight. This song is a huge challenge for any cast, because it is happens right after the Rumble-gone-awry. To have a such a comedic song after so much tragedy seems inappropriate at best. However, I was delighted and laughing by the end of the comedic number. The choreography was creative and had the right balance of sharp and soft, fitting the characters beautifully. The Jets’s performance was flawless and fresh. Their vocals were clear and polished.

The choreography and all the technical elements came together in several memorable scenes like, “The Dance at the Gym.” The choreography was smooth and continuous, like a Gene Kelly dream sequence. The dancers executed it well, particularly Shannon Conboy as Velma dancing with Riff. Conboy brought so much passion and strength, she was captivating, and the chemistry between Velma and Riff was palpable. The costuming of the Jets and Sharks added so much movement and color to the visuals in this scene. Chris Wood’s lighting design throughout the dance was masterful, from the way it sparkled off of dresses and the dropped, festooned ceiling to the intensity it added during the dance off. Then Maria and Tony were suddenly alone on stage, the light marking out their own little world. The circle of light closed around them as the other dancers entered in the shadows. Then the light widened suddenly to include everyone, giving the effect of a cinematic slow-motion scene. The light design set the mood and was often the knock out to my emotional gut. During the scene change from Doc’s shop to Doc’s cellar, the slow dimming of the lights as the characters, “clean up,” the scene by changing the set, the silhouetting of Doc comforting Baby John, and finally the ominous back light into the cellar window where Tony is waiting scared, was one of the most masterful lighting designs in the show.

The show was strong in all technical aspects. The set design by Heidi Hoffer was remarkable—like if Frank Lloyd Wright worked for IKEA. The set was strong, beautiful, functional, and smart. The facade of row houses was the base for several scenes with movable stoops. The rows and stoops framed the stage and gave so many levels for the performers. The overhead space was dramatically utilized, with beautiful draping streamers during, “The Dance at they Gym,” and stunning arches under the highway for, “The Rumble,” and the death scenes that was reminiscent of one of Dante’s levels of hell.

The thoughtfulness of costume designer Amanda Profaizer showed from the beginning, with the Sharks subtlety costumed in red hues and Jets in blue. The color of Maria’s dresses matched the character and her development. The first white dress matched her innocence and brightness, while the blue dress in the last scene called on both the Jets’s color and Maria’s virtue. While I loved how the dresses of the Sharks’s girls looked during the dance with the Jets, when the girls were alone later during, “America,” the colors and textures seemed to clash and mismatch.

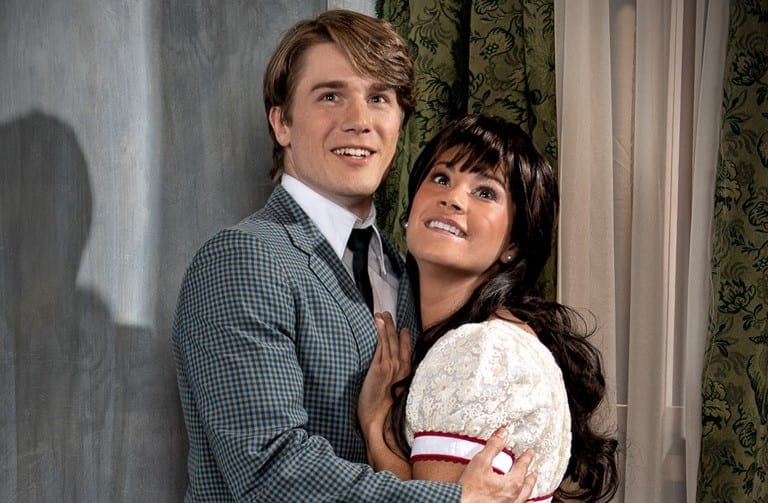

A huge part of the success of the show goes to Olivia LaBarge, who played a sweet and strong Maria. Her acting was vulnerable, especially in the scene where she put on her dress for the party. The dress was sparkling, just like her love scenes with Tony. LaBarge as Maria was committed, sincere, and immersive, especially when she mourned Tony’s death and turned her grief into a challenge for the community to be better. Her vocals never missed; they were clear and bright and yet had a depth of color. At the same vocal level is Marianthi Hatzis who played Anita. “A Boy Like That,” and, “I Have a Love,” aren’t great songs by themselves, and yet LaBarge’s and Hatzis’s vocal prowess and emotionally-charged acting held me captivated. The two brought me to my emotional knees as they dropped to theirs on stage. The two actors made the most of every moment, every note, and every physicality. LaBarge’s and Hatzis’s performances were earnest and raw while displaying amazing vocal depth.

Other powerhouse acting performances came from Broderick O’Neal’s Riff. O’Neal as Riff commanded the stage when his fellow Jets were on it. The way O’Neal played Riff’s fatal blow—as surprised and terrified—was beautifully pathetic and moving to me. Chino played by Jeremy Hurr was the tough guy and the grief-stricken brother, particularly when Chino told Maria of Bernardo’s death. Baby John, played by Ashton Lambert, was full of charisma from the first scene. Lambert as Baby John showed the most depth throughout the story’s tragic events. Pasqualino Beltempo’s Bernardo had me pumping my fist with him during his speech about the injustice Puerto Ricans had experienced. Action, played by Ty Koeller, was an energetic powerhouse, driving the scenes, building the tension, and filling the hole after Riff’s death. Max P. Fowler’s A-Rab was committed in every scene, bringing so much life and authenticity to the action around him. W Lee Daily played Doc’s range of kindness, virtue, and firmness with alacrity.

The show could be improved by a few actors. While Benjamin Adams’s vocals as Tony were powerful—his falsetto sweet and beautifully blended with LaBarge’s voice—the acting in many of his solos was stiff. Adams did not convince me he was a passionate character, either in his love for Maria or in the rage that caused him to kill Bernardo. The character of Schrank was detestable and complex. While Christopher Seefeldt succeeded in making me hate his character, with more thought Seefeldt could also bring out his character’s complexity.

The technical and performance elements united again during, “The Rumble,” when Riff and Bernardo died. Excellent stage fight choreography by Stefan Espinosa was executed well by the cast. A frantic energy of the scene was created by the actors and the orchestra. Combining all that energy with gritty lights, tolling bells, and a slow curtain drop left me holding my breath. This scene was outdone at the end: Tony’s and Maria’s short but piercing duet, Tony’s death and then Maria’s impassioned monologue with Chino sobbing in the shadows, a blood-red scrim with Krupke, Schrank and Doc silhouetted against the scene as the two gangs file out two by two in a grim truce. I was moved to tears.

In the end, I was impressed with the quality and passion in this production even though I don’t love the story. Romeo and Juliet celebrates a problematic version of love, and the gang violence and racial slurs in the setting make me deeply uncomfortable. And yet, I was wrapped up and emotionally moved by this performance. It got me thinking, feeling, and empathizing, which is what good art does. I recommend this to audiences mature enough to make sense of the violence and issues of race and who are looking for more than just a fun show.

[box]The Utah Festival Opera and Musical Theatre’s West Side Story plays at the Ellen Eccles Theatre (43 Main Street, Logan) on July 6 and 30, 2019 and August 3, 2019 at 1 PM and July 12, 17, 20, 26, 2019 at 7:30 PM. Tickets are $12 (for children) to $79. For more information, please visit their website.[/box]