SALT LAKE CITY — Pioneer Theatre Company’s production of A Case for the Existence of God by Samuel D. Hunter, directed by Timothy Douglas, is presented at the Meldrum Theatre at the Einar Nielsen Field House. It is a lovely and modern space that is used for the company’s more intimate productions. Intimate, of course, being relative as the Meldrum theatre still seats nearly 400 people. It is indeed a smaller – and much more comfortable – venue than the main stage alternative. The seats are wider and well-cushioned, with surprising legroom. This venue is a welcome part of a trend of modern theatre spaces taking hold across the state

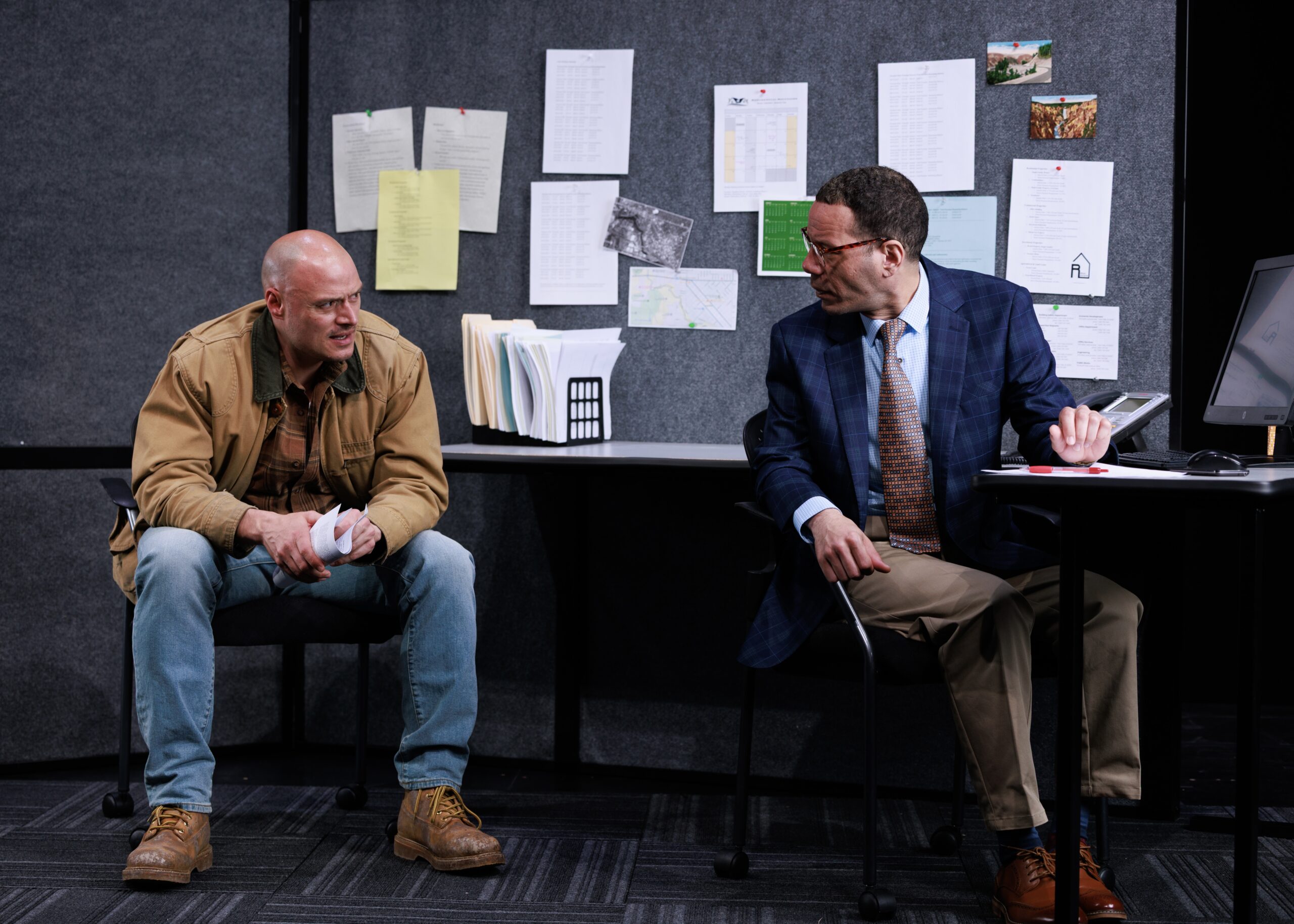

Walking into the space, patrons are met with a stark, smallish set, by Lex Liang, occupying only a fraction of the stage. Set on an elevated platform is a grayish office cubicle, accessible on all sides by several stairs, covered in ubiquitous gray industrial carpeting. Two standard-issue, plastic rolling office chairs, a desk and other typical cubical furnishings occupy the drab space while a florescent light hovers above, the black stage and black scrim flank the floating island of insipidly.

The lights dim, and two men enter the space to occupy the two chairs. The scene begins with several moments of silence, allowing audience to absorb a first impression of these two men, seated across from each other in the tiny office. In the silence the audience is given a great deal of character information. Ryan, played by Lee Osorio, is large, with ashaved head, rough workwear, stained boots, manspreading to overflowing out of his too-small chair. Keith, played by Jon Hudson Odom, by contrast sits delicately, legs crossed, bespeckled and tidy in front of the computer. It is clear that this office, with its orderly papers tacked to the fabric covered cubical panels, belongs to Keith and Ryan is a maladroit guest in Keith’s space. Ryan shifts uncomfortably, flipping through a packet of papers. After a perfectly long and awkward amount of time, the silence is broken with tight, overlapping, and expertly delivered dialogue.

When the dialogue begins, it is breathtaking in its economy, authenticity and nuance. Hunter’s dialogue is dense and tight, while simultaneously full of space for what is unsaid. Hunter is a master of organic language, and Odom and Osorio, under Douglas’s direction execute it with perfect artistry. I instantly feel as if I’ve known these two men my whole life. Which I have—they are in many ways archetypes at spectrum ends of the everyman.

As the two men begin to discuss mortgage details, I wonder where this will go, and whether it will be sustainable. But the mortgage transaction is but a ruse, a vehicle for a much more intricate story of connection, of unexpected empathy and shared pain. The two men, we discover are fathers, connected by a chance encounter at their daughters’ daycare, and brought together by the banal transaction of a mortgage Ryan is seeking to obtain through Keith, a mortgage broker. But their relationship evolves and expands beyond the transactional constraints, developing into a deep, and unexpected friendship built on a bond of empathy.

The two men remain seated for almost the entire duration of the play. I was so intrigued by this choice that I acquired a copy of the script the minute I got home to see if this was the director’s choice, or the playwright’s. It turns out that Hunter wrote it that way—the stage direction says “Unless indicated, neither character ever stands up”—a challenging direction, which Douglas handles expertly. Throughout the production I wondered whether this imposed limitation would begin to feel like a contrived bit. And it almost got there—towards the climax of the plot arc, it seemed the tension holding them to their chairs was going to burst and surely they would have to release it by standing. And then, just when I’d resigned myself that it was going to be carried on too long to be believable, the pent up tension propels Keith to nearly explode from his chair. The moment both leave their seats is so unexpected after the strict convention established to that point of the production, that it is visually shocking in its contrast.

The two actors are extremely skilled and perfectly cast. Their commitment to their characters is magnificent. Their mannerisms are precise and natural and convey so much detail about each character nonverbally. And yet, they also both perfectly inhabit Hunter’s world and words. Ryan’s continual rubbing of his head, face and eyes are familiar and nuanced movements of a man uncomfortable with himself and his situation. Keith’s panic attacks are visceral, and so real that perhaps a trigger warning is in order for anyone who suffers such attacks. Together with Douglas’s direction, which is intentional without being too heavy handed, the character and relational development is so authentic and natural that nothing feels scripted. The playground scene stands out to any parent, in its humor and in its accuracy. Keith’s verbalization of the inner panic of a worried parent creates a monologue that is painfully relatable.

Transitions of time and place happen instantaneously and the first time the scene jump places I found it a bit confusing to reconcile the move from office to Keith’s home. But by the second or third time the space changed, it became an easy convention to accept, especially as the lighting and slight costume shifts better facilitated the changes. Yael Lubetzky’s subtle, but appropriate lighting transitions are expertly executed, taking us from office, to park, to living room, to the plot of land Ryan hoped to purchase. Coupled with Lee Liang’s scenic design, and subtle changes in costume design (also by Liang), the scene is perfectly set. Matt Mitchell’s sound design is limited but powerful. There is a moment, where a piece of music the characters describe in depth in the preceding scene, is then heard. It seems to emanate from Keiths heart and then rises to fill the space before being abruptly cut off. Small technical moments like this and many others from the entire artistic team support and in many ways complete the poignant story.

The end of the production is beautiful. Visually stunning—a sheer curtain appears behind the formerly black scrim and now destroyed office space. The curtain fans in a way that it seems to push out over the two actors, now inhabiting a sort of timeless but future space, propelling us all to an unknown future with the hope that maybe everything will be “okay”.

A Case for the Existence of God is a relational drama. With only two characters, in many ways polar opposites, brought together by mundane circumstances, who find themselves in an unexpected friendship built on very different life circumstances with an undercurrent of similarity, or “shared sadness” as the script labels it. The script is a master class in finding commonality and empathy across experience. The production is not showy. The pacing is deliciously slow, allowing the themes to infiltrate and soak into the audience. But neither is it overly long or tiresome. At about 100 minutes, with no intermission, it feels just right. I love productions that leave me with much to contemplate as I leave the theatre, and this is such a production.

[box] A Case for the Existence of God plays through April 12 in the Meldrum Theatre at the Einar Nielsen Field House on the University of Utah campus (300 S 1400 E, Salt Lake City). Tickets are $44-$57. For more information, visit pioneertheatre.org. [/box]