OREM — How to Succeed in Business Without Really Trying is one of the shows with a reputation that many productions fail to live up to. One of the few musicals to ever win a Pulitzer Prize, How to Succeed . . . is a tough show to execute. It requires a deep bench of strong male musical theatre actors, great choreography, and a talented director that can handle the dated script and satire. Luckily, Hale Center Theater Orem had all the ingredients to make the show work. HCTO’s How to Succeed lives up to the play’s reputation with a production that is as successful as its main character’s career.

How to Succeed is a satire on big business. The script (by Abe Burrows, Jack Weinstock, and Willie Gilbert and based on a book by Shepherd Mead) tells the story of an ambitious young man, J. Pierpont Finch, who uses an instruction book to climb the corporate ladder from window washer to executive. Though the show premiered in 1961, some of the targets of its script still apply: the clueless boss, the sycophant coworker, the endless parade of meetings, and more. Other aspects of the script have not aged well. The sexism of the early ’60s pervades the story, and aspects of the show are a tough sell in the 21st century. This is a challenge for modern productions, but it is not insurmountable. After all, theatre companies still produce Grease and Seven Brides for Seven Brothers. If a modern audience can accept those shows’ views on women, then they can accept How to Succeed.

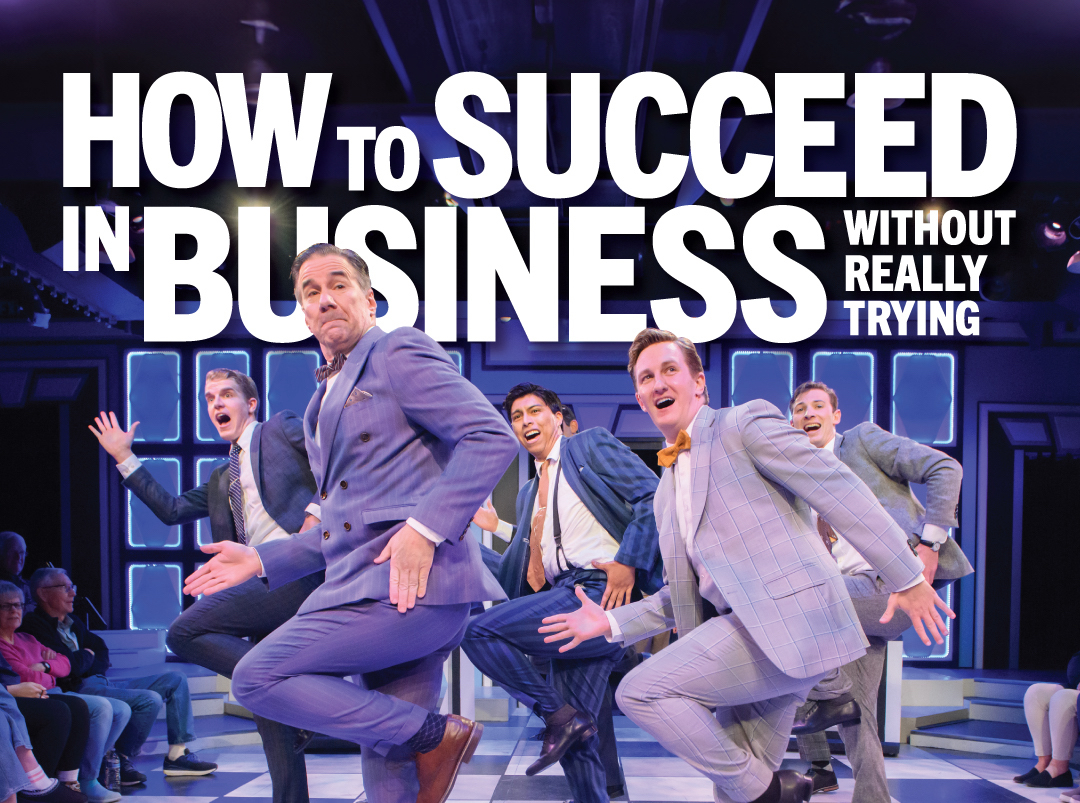

Director Jennifer Hill Barlow solves this problem in two ways. First, she presents How to Succeed as a period piece. Barlow’s direction strives for realism and to be faithful to the social conditions of the time. The costume and set designs helped greatly in this regard. Costume designer Elizabeth Banks Wertz dressed the female characters (all of whom work as secretaries) in high heels, nylons, and period dresses, while she gave the men blue, gray, and black suits in solid, plaid, and windowpane patterns. Scenic designer Jason Baldwin created a retro set that exuded the feel of the early 1960s, with geometric panels that housed LEDs, large faux tiles on the floor, and period industrial lamps hanging from the ceiling. Both costume and set designs had meticulous details that transported the audience to the time period and made the play a realistic portrayal of the attitudes at the time — without endorsing them.

Barlow also handled the story by distracting the audience with good, old-fashioned musical theatre razzle-dazzle. Nearly every song in Frank Loesser‘s score provided delightful little surprises for Izzy Arrieta‘s choreography. For example, “Coffee Break” featured convulsion, and “Rosemary” had an unexpected pas de deux. But the champion song was the show-stopping number “Brotherhood of Man.” Its energetic dancing filled the stage and was accompanied by a light show (from lighting designer Ryan Fallis) that accentuated the dancing and music to create a song that was everything a musical theatre lover could want. By creating such supremely enjoyable moments in the songs, it is easy to forgive the dated aspects of the script of How to Succeed. Yes, I still cringed at the men ogling Hedy LaRue, but the dancing of “A Secretary is Not a Toy” is so precise and clever that the moment of discomfort is a small price to pay for the superb dance scene that comes afterwards.

The cast for How to Succeed might be the best that HCTO has ever assembled. Nick Garner leads the cast as J. Pierpont Finch. Garner’s gleeful smile, affable nature, and charisma make him perfect for the role. With Garner’s performance, it is so easy to see how Finch could smooth-talk his way to a promotion. Garner also has the ideal voice for this score; his singing is controlled, clear, and shows no hint of fatigue at any point throughout the show. I especially appreciated the range of style in Garner’s singing. “Rosemary” floats through the air gently, while “Grand Old Ivy” has the passion and power needed for a college fight song. As Rosemary Pilkington, Abigail Watts is a treasure. Her wistful rendition of “Happy to Keep His Dinner Warm” won me over instantly, and her dreamy beginning of “Paris Original” set up the song’s humor nicely. Watts also infuses some intelligence into Rosemary as her character manipulates Finch into asking her on a date — a moment that brings some desperately-needed depth to the character.

The scene-stealer of How to Succeed is McKell Rae as Hedy LaRue. Rae plays the bombshell stereotype well, and she milks the humor in all of her scenes, especially “Love From a Heart of Gold” and the pirate dance. Rae understood how to make her character both sexy and the comic relief. Hedy’s giddiness at performing on television was a highlight of the evening because of the layers in Rae’s performance. Many actors struggle with playing a character who is performing poorly, but Rae disappears, and the performance seems to come solely from Hedy’s excitement and inexperience. Joseph Paul Branca had an innovative take on Bud Frump. The character is scheming and conniving — as he should be — but Branca added a layer of cattiness to Bud. This was a new performance choice that emphasized the jealousy that Bud had towards Finch. It is gratifying to see that a talented actor can still bring new ideas to a classic theatre role.

The ensemble pours their soul into their performances. I was especially impressed by the male ensemble, who danced and sang with passion without wearing out the creases in their suit pants. The female ensemble is best in the hilarious song “Paris Original” and in establishing the busy office atmosphere. In every scene, this ensemble strengthened the play and made me grateful to bask in their talent.

However, the most surprising “performance” comes from Fallis’s lighting design. The LEDs surrounding the rectangular panels upstage and around the theater changed color to provide appropriate mood lighting for many scenes. Most gratifying was that during the songs, panels would light up, change colors, or form patterns at instances that matched the percussion or lyrics of a song. At times, such as “Brotherhood of Man” and “Coffee Break,” the lighting was an extension of the choreography. This unity of movement, music, and lighting was the memorable and exciting aspect of the entire production. (Kudos to stage manager Tannah O’Banion for flawlessly calling and/or executing several hundred light cues in the evening.)

Thanks to a talented cast, Barlow’s flawless directing, Arrieta’s exuberant choreography, and designs that transported me back to the swingin’ sixties, How to Succeed is a triumph. Indeed, the show is so good that I could enjoy How to Succeed Without Really Trying without any “trying” on my part.

[box]How to Succeed in Business Without Really Trying plays nightly (except Sundays) at 7:30 PM (with matinees at 12 PM and 4 PM on Saturdays) at Hale Center Theater Orem (225 West 400 North, Orem) through April 13. Tickets are $31-49. For more information, visit haletheater.org.[/box]