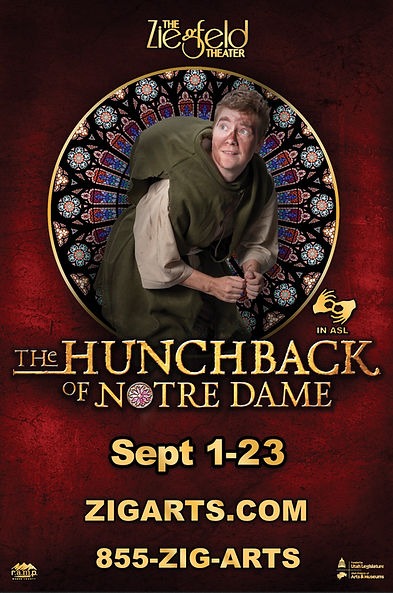

OGDEN — Walking into the Ziegfeld Theater feels like coming home. I have only seen one other production at the Zig and had nearly forgotten the feeling of joy, inclusion, and family this well-loved space exudes. And opening night of the company’s The Hunchback of Notre Dame overflowed with it. Yes, Hunchback has darker underlying themes, but what floats to the surface in the musical adaptation (with music by Alan Menken, lyrics by Stephen Schwartz, and a script by Peter Parnell) and as executed by the Ziegfeld Theater Company, are the themes of friendship, inclusion and love.

The Zig’s Hunchback deftly hones in on these themes, especially that of inclusion, as this is the company’s annual ASL/English musical production. This is a full production performed in American Sign Language and English simultaneously, not a performance with ASL interpretation. It was the ASL and English presentation format that I was most anticipating about this production, and I was not disappointed.

The stage at the Zig is not large. Staging a big musical with a cast of 20 is ambitious and challenging in this space. The set, designed by Caleb Parry is necessarily simple in order to allow the space needed for so many actors, and yet it still manages three performance levels with gothic-inspired staircase and railings. Of particular note is the production’s use of projection on both sides of the stage as well as the back wall. The projections (designed by Steve Hill and Lucas Hill) enhance the production, providing both a means to quickly expand the space with vaulted cathedral ceilings and beautiful stained-glass windows, as well as give the show a modern upgrade. The projections also help move the action across Paris from one locale to another. Although the physical set pieces denoting the various locations are clever, the “Topsy Turvy” and “Court of Miracles” scene changes in particular are clunky and would benefit from more practice and perhaps less set dressing to allow for smoother transitions.

The soaring vocals of the opening song, “The Bells of Notre Dame” highlights some key vocal talent in the cast. A particular highlight in the opening number is Ginny Teuscher, whose voice left me wishing for more. Fortunately, Teuscher is also cast as Klopin, the King of the Gypsies, a role normally sung by a tenor. Although Teuscher plays a strong Klopin, there are times it is apparent that the part is at the bottom of her vocal range, where she is not as strong, which is unfortunate, as she clearly has a stellar voice that is better showcased in the other ensemble parts she plays. Additionally, Andrew Stone (as Young Frollo) and ensemble members Aurora Nelson and Chloe Price contribute strong vocals, despite often faulty microphones.

The biggest challenge of the opening number is clearly communicating the exposition and setting up the story. Unfortunately the sheer number of people on the small stage, the movement, the overlapping vocals, and some issues with sound (both in the mixing of volume and microphone malfunctions) all contributed to a general muddiness. The same issue occurs at the production’s climax in “Kyrie Eleison.” While the production uses underlying vocal tracks effectively to sweeten the big choral numbers, there are times when the skill of the live vocalists and key exposition is lost.

Despite the muddiness, it is the first scene that establishes the dual-language ASL/English convention and delivers the goal of co-directors Morgan Parry and Anne Post Fife had of harmonizing these languages. The ASL flows around and through the characters—sometimes one signing for another, at other times characters sign for themselves, and often both at once. This interplay creates a visual dance, a feast for the eyes, drawing the audience into the world of the play.

The most distinctive and lovely convention in the production was to have deaf actor Britton Auman play Quasimodo, and the character voiced by Samuel Teuscher. What is unique about this convention is that Teuscher is not acting as Quasimodo’s interpreter. Instead, both actors are playing Quasimodo at the same time, creating a rich duality of character. In many ways Teuscher plays as an inner voice to an outwardly hearing-impaired character, and yet simultaneously both Auman and Teuscher embody two halves of the same person. Auman usually leads the action, while Teuscher follows, but even at the times in which Teuscher takes the lead, the two performers are deeply interwoven. Auman and Teuscher complement each other in a singular way; Auman’s physical embodiment of the role and depth of emotion in his sign language is heartrending, while Teuscher’s vocals are spectacular. One odd directorial choice occurred at several moments when Quasimodo joyfully rings the cathedral bells, swinging from a large rope. The audiences can see the bells appear overhead, yet often there is no bells playing in the track, which is an unfortunate omission.

Along with the sound issues, the biggest hurdle the production faces is the staging. Parry and Fife’s staging varies from beautiful to awkward. Where the staging falls down is particularly when scenes are cramped into center stage, such as the end of “God Help the Outcasts” and “Made of Stone.” Both of these numbers do not utilize the full cast, and yet they feel crowded unnecessarily into the center of the stage, as actors are almost tripping over each other or blocking one another from view. Scenes with the full cast, like “Topsy Turvy” and “The Tavern Song” are crowded, but intentionally so, which works to the production’s favor as the small space creates a desired feeling of a large crowd. Towards the end of the second act, after Esmerelda’s death, there is a lovely use of space as the entire ensemble frames the heartbreaking scene at the center. Fife and Parry have placed the ensemble at the edges of the space on all levels, creating a beautiful tableau focused on Emeralda. Disappointingly, this is followed by a missed opportunity in the staging by describing the final image of Esmeralda and Quasimodo without showing it. Instead, the actor narrating physically blocked what could be a magical and powerful visual element if the scene were opened up.

There were also some pacing issues in the first few scenes. There is a significant amount of exposition to get through, and the sound challenges and opening night nerves resulted in a low-energy performance. That was remedied with the entrance of Mak Milord as Esmeralda. When she appears in “The Rhythm of the Tambourine,” she is captivating. Milord is full of vibrancy, energy and sensuality. Milord’s Esmeralda is a force to be reckoned with. She is big, bold, and beautiful, and her vocals throughout the production are exquisite and powerful. Her character is sincere and engaging throughout, despite sometimes rushing her lines.

The Hunchback of Notre Dame at the Zig is truly unique and well worth an audience’s time. The Ziegfeld’s stated motto is “professional standard, community spirit.” This community spirit shines in this production of The Hunchback of Notre Dame, as the audience is warmly welcomed into the Zig family.

[box]The Hunchback of Notre Dame plays Fridays, Saturdays, and Mondays at 7:30 PM through September 23, with extra performances at 2 PM on September 9 and 16 and 7:30 PM on September 21, at The Ziegfeld Theater (3934 South Washington Boulevard, Ogden). Tickets are those performances are $22.95-24.95. The production will then play at the Egyptian Theatre (328 Main Street, Park City) from September 29 through October 3. Tickets for those performances are not available at publication time. For information about the Ogden performances, visit zigarts.com. For information about the Park City performances, visit parkcityshows.com.[/box]