CEDAR CITY — New works are always exciting. To have the chance to actively participate in the creation of art, or to bear witness to the workshop process is a bit like Charlie winning the golden ticket and getting to see behind the scenes of the chocolate factory. New works are a good reminder that art is alive and is a natural and necessary response to the human experience.

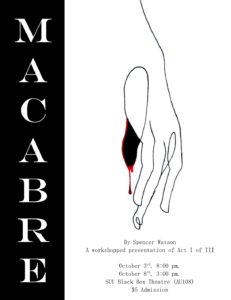

Macabre is a new work in development by Spencer Watson and made possible by the Black Box Grant from Southern Utah University. UTBA was invited to review a workshopped production of Act 1 of Macabre, and I snatched up the opportunity.

Macabre, Act 1 follows three art professionals: a painter, a critic, and a gallerist, as they study and debate a new work of the painter. The new work is dark and macabre, as the play title would suggest and sparks heated conversations about the nature, purpose, and power of art. Throughout the scene, the history and relationships of the professionals are revealed as the artwork provokes memory and conversation. The characters are portrayed by Whitney Black, Elise Thayn, and Jessica Channa Sannar.

The play opens on the three professionals and a long, long, very long silence. The silence, to the actresses’ credits, pulsates and anticipates what will prove to be a very full, rich, and quick script. As soon as the silence is broken, the Watson’s script is unleashed and does not pause for breath for the rest of the act. Macabre is a true ensemble piece, with each character given distinct and striking personalities, intelligent and humorous lines, and a reason for the audience to take their side. I rooted for each character, and I vehemently disagreed with each character. The slow reveal of the characters’ interconnected histories keeps me invested in every story and interaction.

The script itself is the Summa Theologica come to life. In the Summa, philosopher Thomas Aquinas follows a standard logical format of raising objections, then a counter-statement followed by an actual argument, and concludes with individual replies. Following Aquinas’s pattern, Watson in Macabre poses questions, suggests answers, and refutes those answers. The difference is that Aquinas will give an authoritative response at the end, while Watson leaves the questions for the audience to answer.

Macabre is full of humor, wit, and intellect and is served well by the fast-talking actresses. The tempo may dissuade some viewers, though, because the material is heavily philosophical and specifically about art and the human condition — not a topic that every theater-goer will be able to follow and invest in. Similar to Dead Poets Society, Macabre may be enjoyed by the masses, but is better suited to those who study the Romantics and their notion of art or those who actively participate in arguments about gallerists vs. critics.

There are moments in the text that take me out of the play. Using “cannot” instead of “can’t” and the overall lack of contractions where they could be leaves a challenge to the actors to sound like real people instead of an academic paper, especially in a script that is already full of big, art-centric words and philosophical questions.

At the very end of the act when tensions are high, the script gets confusing. The “Pandora’s box” speech in particular seems out of place and contradictory. It is jarring and confusing when Elma proclaims that “nothing happened” and immediately contradicts it once Kaydence leaves the room. At one point, Elma seems okay with knowledge of a bribe, but at a different point seems to not know anything about it. Elma’s last scene, where she stares at the piece as applause is heard overhead, also sets up a contradiction with what the artist wants from her latest work. Overall, the script flows nicely but gets convoluted towards the end of the act.

I cannot imagine these characters as anything other than what Black, Thayn, and Sannar, bring to the stage. The calculated and demanding presence of Thayn contrasts perfectly with the grungy wallflower portrayal by Black and the over-caffeinated performance by Sannar. Each actress brings power and passion to their character in completely different ways, making it hard to pick a lead or a protagonist. The actresses match each other well in pace and chemistry. I can actually believe that I am watching three professional women rehash their college relationships.

Macabre is a piece of art by and for artists. I left the theater with a lot more questions than I came in with: questions about aesthetic, psychology, purpose, and danger in art. I left the theater excited to see more of Watson’s work.

[box]Macabre played on the campus of Southern Utah University and has closed.[/box]