SALT LAKE CITY — Fences tells the story of Troy, a has-been baseball player who missed the big leagues because of the unfortunate combination of the color of his skin and the year of his birth. Against the backdrop of this injustice, Troy optimistically fights the union to allow African-American workers to drive the truck while pessimistically denying his son Cory a chance to make it as a football player. In fact he lives much of his life in opposition, joking on the front porch with his wife Rose and longtime best friend Bono while wrestling with the knowledge of his affair with Alberta. None of Troy’s problems manifest themselves quietly. His son Lyons, a musician, comes by on payday to borrow money; his brother Gabriel’s mental handicap lands him in jail; Cory’s deceitful attempts to pursue football finally culminate in Troy’s decision to kick him out of the house; Alberta dies in childbirth, leaving Troy to plead with Rose to raise his innocent child. Scene by scene Troy wrestles aloud with death, recounting his past encounters with its personified form. Board by board he builds a fence for Rose, a fence she envisions will keep the family in but ultimately cannot keep death out.

In keeping with the show’s frequent allusions to the game of baseball, I’ll indulge a comparison. For those who love the sport and are familiar with its details, the long nine innings carry a sustained energy despite the natural lulls of the game. However, for those less attuned to its nuances, the lengthy stretches of apparent inactivity can feel arduous and interrupt any potential momentum. While I was able to recognize moments of beauty and brilliance in this Pioneer Theatre Company production, I struggled to maintain complete engagement through the ebb and flow of the show’s intensity. Unable to find a deep, personal connection, I found myself longing for the next highlight to force me mentally back on my feet.

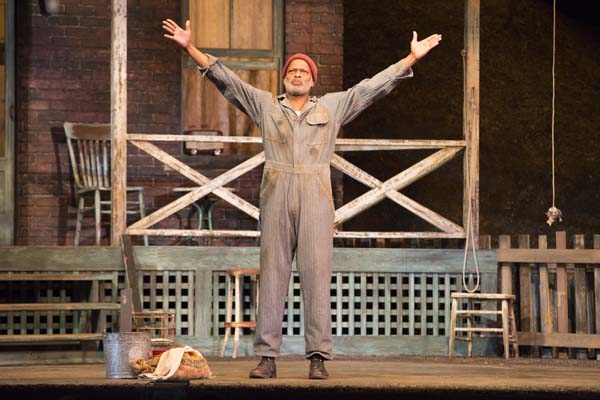

Although my personal connection lacked, it was easy to see the connection director Timothy Douglas had fostered between the actors and their assigned roles. This was most evident in the moments which called for them to interact in silence. During frequent monologues delivered by Troy (played by Michael Anthony Williams), I enjoyed observing Rose (played by Gayle Samuels) and Bono (played by Jeorge Bennett Watson) as they reacted in natural but convicted ways. Samuels would often nod or lean forward while Watson used the firm set of his jaw to respond subtly to Troy’s phrases. It was also evident in their body language. Jimmie “J.J.” Jeter gave the high school character Cory a slight hunch and turned feet to develop the idea of his youth and subservience while Jefferson A. Russell chose frantic hand motions as an allusion to Gabriel’s handicap. Even in Jeter’s confident use of a hand saw to cut the fence boards to the precise length I witnessed a reality that showcased Cory’s growing strength.

Spanning approximately seven years, this script allowed plenty of time for each character to undergo significant changes. These were reflected in meaningful ways in each character. As Troy became ruled more and more by his fears, Rose became more empowered in herself. Cory eventually learned to stand straight in his marine’s uniform. Raynell (played by Meg Hoglund), the daughter Rose raised after Alberta’s death, grew to offer a carefree innocence otherwise inaccessible to the characters.

In the lulls I found myself drawn to the set designed by Tony Cisek, a two-story brick house jutting out from a pile of rubble. I enjoyed peering through the glass front door into the kitchen, especially when Rose had gone inside. As Rose, Samuels spoke volumes with her back turned, dealing with her emotions out of Troy’s sight. One of my favorite moments featured Cory and Raynell standing near the corner of the front porch, positioned as two forward points of a triangle. Unknown to them, Rose stood on the other side of the glass door, anchoring the triangle’s third point. The reality of the mother being an unseen but integral part of the story echoed the reality that this production seemed to be trying to capture.

Meandering through Troy’s story as it unfolded naturally allowed playwright August Wilson to capture both the essence of real life and its monotony. As the fence neared completion and the conflict intensified, I could see how the expository scenes of Act I lend strength and depth to the strain of Act II. Draining my energy in the same way that a hard day of real life does, Fences did not intend to entertain; rather, the cast set out to tell Troy’s story and invite the audience to consider the realities of an African-American existence in mid-20th-century America. Although it takes time to build, Fences is a sound investment.

[box]The Pioneer Theatre Company production of Fences runs through January 21 at the Simmons Pioneer Memorial Theatre (300 S. 1400 E., Salt Lake City). Tickets are $25-$49. For more information, visit www.pioneertheatre.org.[/box]