SALT LAKE CITY — It is not very often that a new play that takes place over 50 years ago is timely. Yet, that is just the situation that Ken Jones‘s new play, Alabama Story, is in as it has its world premiere now at Pioneer Theatre Company. With events in Ferguson, Missouri, New York City, and elsewhere forcing Americans to grapple with their country’s racial history, a play about a minor event in the Civil Rights Movement gives audiences a chance to explore America’s struggle to live up to its founding ideals through social, racial, and historical lenses. UTBA recently discussed Jones’s career as a playwright and theatre journalist to learn more about the creator of this probing play.

What first made you want to become a writer?

JONES: I fell in love with the theatre as a kid when I was growing up in suburban Detroit. My parents took me to the theatre — to national touring shows that would come into Detroit’s Fisher Theatre and Masonic Temple Theatre, and to some of the smaller resident Equity theatres, too — Meadow Brook Theatre and the Attic Theatre. I thought theatre was magical and I wondered if I might one day have a career in theatre. I was too shy and repressed to be an actor, so I began to write stories and plays, thinking I might be a playwright. It’s a dream that I put on hold for many years because I had no role model or mentor for creative writing, and at that time —the 1980s — the resident theatre in Michigan was not particularly nurturing to new voices, young writers, new plays. (That has changed.) It didn’t occur to me that there might be playwriting programs at universities.

What made you want to write for and about the theatre?

Jones: In high school, I wondered and worried how I would make a living as a creative writer. I was always interested in journalism and decided very early, even before college, that I would switch to journalism, with the goal being a theatre critic — it was a way to stay connected to the theatre. I had this insane goal that I might one day be the theatre critic at The Detroit News, covering the same sort of big tours and resident productions that I had seen as a kid.

After I got a journalism degree, I became a freelance theatre critic, entertainment writer and theatre reporter for a suburban Detroit paper and by 1989 I sold my first review to The Detroit News — a review of the first production by Jewish Ensemble Theatre, an Equity troupe that still operates in Michigan. Six years later, I became chief theatre critic at The Detroit News, one of the happy accomplishments of my young life. I was very serious about being a theatre writer: I loved being an advocate for the theatre as both an objective reporter and a subjective and informed reviewer. I never socialized with theatre people, I didn’t hang out and go to cast parties, I sought to be an independent voice.

How is writing for the theatre different than writing about the theatre? Do they influence each other?

JONES: I saw probably 600 shows in 13 years of covering theatre in Detroit, learning about dramatic form by absorbing and interpreting it. I didn’t know it would be the perfect training ground for being a dramatist — I learned about storytelling structure two ways: by studying the classics and by simply writing features and reviews.

Crafting journalism pieces is analogous to playwriting — in one way or another both products need to convey some sort of beginning, middle and end. On top of my career in Michigan, I was theatre reporter and editor for Playbill.com in New York City for 15 years. All good writing is about good editing and rewriting, and so 25 years of that made me a better storyteller.

How and when did you make the switch to dramatic writing?

JONES: From Detroit, I worked long distance with a New York composer named Roger Anderson. I wrote lyrics and he wrote music. We talked about working on some musicals, and ended up with a bunch of nice songs.

I moved to New York City in 1998 when I felt that The Detroit News’ commitment to arts coverage was dwindling. I needed a second act in my life and I thought I would move to New York, take any sort of day job, and start writing plays and musicals. Of course, I almost immediately landed a job at Playbill, but I also kept one foot in creative writing. I auditioned for and got into the BMI-Lehman Engel Musical Theatre Workshop, met a community of wonderful artists and wrote two musicals, VOICE OF THE CITY and NAUGHTY/NICE, which had readings and workshops; the former was directed by Karen Azenberg.

In 2013 I sent her my ALABAMA STORY script and she embraced it, directed readings of it in Alabama in May 2013 and then in Pioneer’s inaugural Play-by-Play New Reading Series in April 2013. Now here we are with the world premiere, through Jan. 24. I am over the moon that she believed in this, shepherded it, and attached such amazing resident and national artists to it.

How would describe ALABAMA STORY?

JONES: ALABAMA STORY is a highly theatrical docudrama that, I hope, thwarts the audience’s expectation of it being some sort of dry history lesson. I regret even saying it’s a “docudrama” because I think it’s more ambitious than just that. It’s a romance, a political thriller, a memory play, a workplace drama, a tearjerker, a comedy, rumination on the power of books, and — most important — a play about how we behave when we face terrible circumstances. The play is about how character is revealed in times of transition, change and crisis. It may begin as a docudrama, but I hope it becomes a potent character study and a potent slice of American history by the end. People are sniffling and wiping away tears by the epilogue, so I think they recognize and relate to the characters’ journeys.

Because the play centers on a children’s picture book, I tried to take a cue from storytelling and “pop-up” books — to break the fourth wall and have actors occasionally explain themselves (in-character) in direct-address. Pioneer Theatre Company artistic director Karen Azenberg, who directs, exploits that, too, and often brings the cast far downstage over the orchestra pit. The production feels very present and punchy. Scenic designer James Noone’s brilliant set seems to be flat and one-dimensional at the start, but the domain of the librarian “pops out,” backdrops change, other locations materialize, light pours in from many angles in lighting designer Phil Monat’s painterly work. He and Karen worked tirelessly in tech, even revising the staging of a vital scene at the very last public dress rehearsal, to give this world muscular dimension and texture.

This story is based on true events, what was it about this story that made you want to create a play?

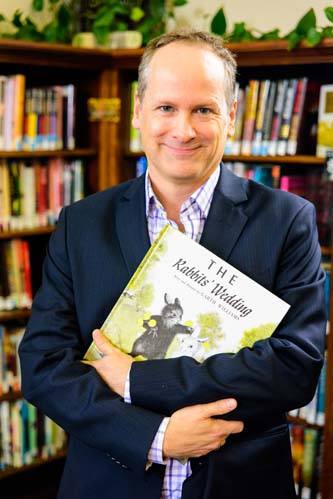

JONES: In May 2000, I was reading the New York Times and I came across the obituary of Emily Wheelock Reed, an 89-year-old former librarian who had been put on the grill by a segregationist state senator named E.O. Eddins in 1959 Alabama. He wanted a controversial children’s picture book — THE RABBITS’ WEDDING, about a black rabbit marrying a white rabbit — purged from the shelves of Alabama libraries. She refused to get rid of it. He later objected to other books that were being promoted by the library. And, later still, he and others sought to legislate Reed out of her job.

Strong characters and richly contrasting conflicts rarely fall into my lap, but opposites — male and female, black and white, insider and outsider, Southern and Northern, child and adult, love and hate, innocence and ugliness — were immediately evident in this slice of American history. I instantly recognized the building blocks for a play. I took notes and began research.

What is your process like, especially when adapting true events into a play?

JONES: I was not interested in a creating a “message” play or a movie of the week. I wanted to write juicy characters, big confrontation scenes and tiny moments of tenderness; a mix of real events and people, and fictional events and people. I borrowed real statements made by the real people — pulling from newspaper stories from 1959 — but I also made my own dialogue. I hope you can’t tell where the “real” ends and the “fiction” begins. People in power positions (like Emily Reed and the Senator) or people whose passions are stirred (like Joshua and Lily — a love story that emerge) tend to speak in a heightened language. I hope they all match and it feels like a weave of style and content and character. I wanted to write about the historical and factual realm in the library tale, and about the spiritual and sensual realm in the Lily-Joshua romance — a reflective storyline that glances off of the main story.

What do you wish you had known when you were starting out as a writer?

JONES: I simply wish that I had started sooner and been more fearless about being an artist. I lived in a time and place where risk and creativity were not particularly nurtured or embraced or understood. I ended up coming of age in my 30s. I wish I could go back and tell myself to be less afraid.

What are you working on now?

JONES: I’m working on several things. My new play is a small family drama about generational differences, Midwest people and feeling like an outsider in your own family. I am also sketching out a new musical inspired by the life of a Gay ’90s songwriter who had a couple of hits but, like many pop writers around 1900, died sick, drunk and penniless. I have a lot of other ideas on pieces of paper in a drawer, too. Usually one of them comes to the fore. I let things brew very slowly. They have to steep for years before it all comes pouring out.

Update: Watch a video of our interview with Kenneth Jones here:

[box type=”shadow”]The Pioneer Theatre Company production of Alabama Story plays Mondays through Thursdays at 7:30 PM, Fridays and Saturdays at 8 PM, and Saturdays at 2 PM through January 24 at the Simmons Pioneer Memorial Theatre (300 S. 1400 E., Salt Lake City). Tickets are $25-49. For more information, visit www.pioneertheatre.org.[/box]