SALT LAKE CITY — A basic description of Alabama Story makes the the story seem like a serious play examining the injustices of segregation in Alabama during the late 1950’s, filled with heightened language decrying racism in poignant monologues haloed in spotlight and surrounded by historical tension straining every scene. But this world premiere at Pioneer Theatre Company is so much more, and therefore so much more powerful.

Playwright Kenneth Jones creates a “Deep South of the imagination” as the backdrop for his inspired-by-true-events fable to unfold. Inspired by his love of newspapers and a happenstance discovery of a long-forgotten dispute between a librarian and a senator, Jones brings a piece of history alive without force or guile. The play—a finalist in the 2014 National Playwrights Conference—is narrated by Garth Williams (marvelously portrayed by Stephen D’Ambrose), a children’s book author and illustrator best known for his drawings for work by E. B. White and Laura Ingalls Wilder. Here, he tells the story of when a children’s book he wrote, The Rabbits’ Wedding, inexplicably became a symbol for integration and pitted an Alabama senator against the head of the Alabama Public Library Service.

It is 1959 in Montgomery, Alabama. Integration is a hotly debated and contentious subject, with both sides believing the other is on the wrong side of history. The civil rights movement is gaining momentum, but there are plenty of southerners entrenched in the idea of keeping things the “traditional” way. When native son and reference librarian Thomas Franklin shows head librarian (and mid-westerner) Emily Wheelock Reed an article from the local conservative paper denouncing a children’s book featuring a black rabbit and a white rabbit getting married, Reed dismisses the scurrilous idea that a book about bunnies getting married could be political or in opposition to the public good. She maintains her stance even when Senator E. W. Higgins (the fictional version of Senator E. O. Eddins) latches on to the news article and claims The Rabbits’ Wedding is dangerous propaganda meant to brainwash southern children into accepting unnatural alliances. Reed and Higgins engage in a political tango over the book, with an insider vs. outsider dynamic feeding the conflict, and the only common ground is respect for the written word. Set in counterpoint is an unexpected reunion of childhood friends Lily—a white woman born to privilege—and Joshua—an African-American salesman whose mother served Lily’s family. Lily and Joshua struggle to find their footing in an adult friendship, but their repeated meetings lead to ultimate understanding.

Director Karen Azenberg has assembled a fantastic ensemble cast, encouraging the storybook quality of the plot while grounding performances in honesty and authenticity. The characters could very easily become stereotypes without skillful guidance. Rather, each becomes a sophisticated archetype, continually reminding the audience that there is always more to be learned from a good story. D’Ambrose is terrific as Williams, providing the narrative frame with a warm no-nonsense style reminiscent of a Mark Twain essay, and he seamlessly slips into the shoes of at least six other diverse characters needed to move the story along.

Greta Lambert’s Reed is made of stern stuff and sees her duty to the public—the whole public—is to provide access to the world beyond through books. Reed could be considered the play’s protagonist, but it is never as clear-cut as that. Lambert is stalwart and vulnerable, portraying Reed as gently rebellious as she maintains her moral obligation to the books and readers she serves. William Parry as Senator Higgins is every inch the good ol’ boy southern gentleman of past eras. Appropriately blustery and capable of delivering fire and brimstone when necessary, he never delves into sleazy bureaucrat territory. While Higgins is the opposition for Reed, his actions are not rooted in malice. Parry and Lambert display all of the subtleties needed for a complex story and superbly explore the difficulties of deciding whether to change with the times or stand firm with what has always been.

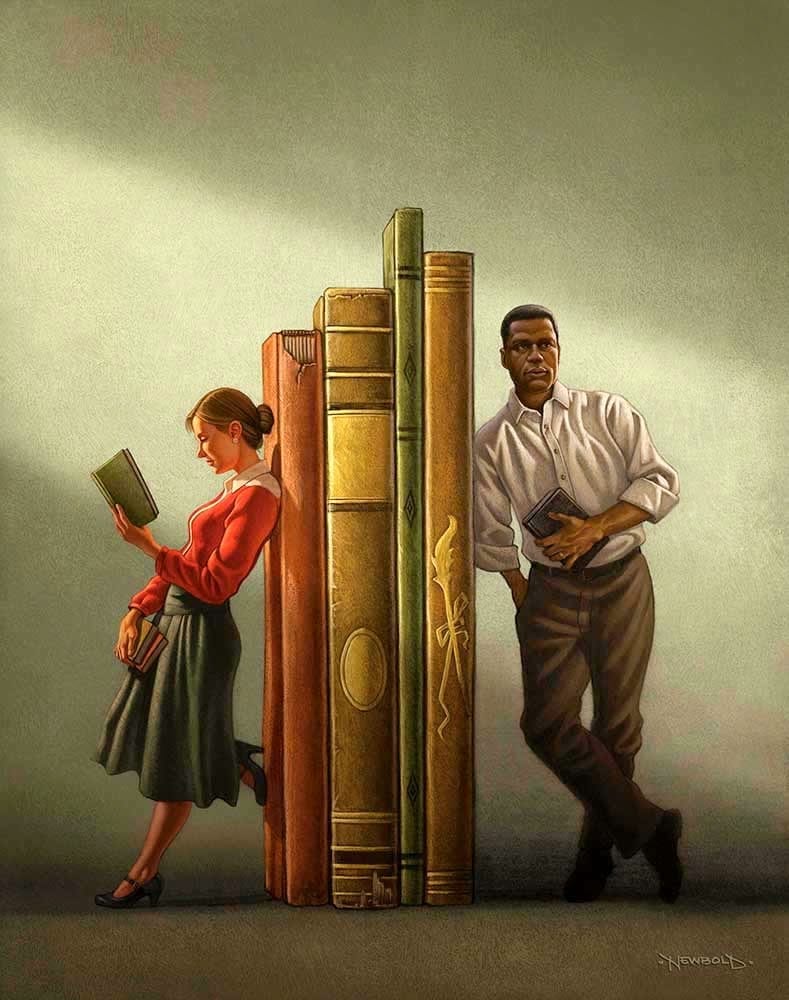

Kate Middleton and Samuel Ray Gates as Lily and Joshua are beautifully nuanced in their portrait of childhood friends separated by time and events bigger than burgeoning friendship. Lily and Joshua could be considered a symbolic version of the black rabbit and white rabbit from the debated book, but I think that this is a deeper character relationship that showcases the need for understanding, forgiveness, and acceptance both sides require to find peace. Middleton gives Lily a delicate strength that is consistently near the surface of her demure southern belle artifice. Lily is a dutiful daughter, wife, and mother; she’s polite to a fault and completely oblivious to the difficulties the African-American population in her state have seen. Joshua isn’t merely a means to the end of Lily recognizing these wrongs, but rather a representation of the other side of the story, a contrast, if you will. Gates provides Joshua with profound kindness, allowing a reunion that could be (or rather, should be) strained to be genteel, and encouraging the second chance they both need. It is a love story, but the non-romantic element makes it so much more compelling and refined because it becomes less about “star-crossed” missed opportunities and more about repentance, recognizing the changes one can make in oneself that can contribute to a greater good.

Lastly, there is Thomas Franklin: Reed’s assistant, protector, proud southern boy, and shy young man. Franklin is probably the most complex character because he fills the role of so many archetypal characters. He is in turn messenger delivering news to Reed, a mentor coaching his beloved superior in southern ways and pronunciation, an ally willing to follow Reed into hell and back, but most importantly a witness to changing times and the perils thereof- standing sentinel to the events unfolding and willing to report them to those who come after. Seth Andrew Bridges is outstanding as Franklin, deftly navigating the layers of his character while serving as the piece’s heart.

The show is technically impressive as well. James Noone creates the granite edifice of the Alabama capital with a huge black and white photograph with the book-lined office of Reed cleverly nestled inside. Phil Monat‘s naturalistic lighting aptly creates the ambiance of Alabama as well as the feeling that of watching old photographs come to life. Costumes by Brenda Van Der Wiel are beautiful, especially the dresses worn by Lily. Hair and make-up by Amanda French complement the costumes and complete the historical feeling. Sound designer Joshua C. Hight used original music by local band Matthew and The Hope to give the show a true southern feel.

With a mix of historical and fictional, Alabama Story truly engages its audience while celebrating the freedom found in books, the power of knowledge, the need for second chances, and the importance of knowing—and telling—stories.

[box type=”shadow”]Update: Read UTBA’s interview with the playwright of Alabama Story.

The Pioneer Theatre Company production of Alabama Story plays Mondays through Thursdays at 7:30 PM, Fridays and Saturdays at 8 PM, and Saturdays at 2 PM through January 24 at the Simmons Pioneer Memorial Theatre (300 S. 1400 E., Salt Lake City). Tickets are $25-49. For more information, visit www.pioneertheatre.org.[/box]