SALT LAKE CITY — Getting Out tells the story of a woman named Arlene who is on parole following her second stint in prison for the second-degree murder of a cab driver. She is a largely uneducated woman from Kentucky, a victim of an abusive childhood and an impoverished adulthood. Her time spent as a prostitute has hardened her and also given her a child, with whom she hopes to reunite.

As the play opens, a warden’s voice comes over the loudspeaker, announcing Arlene’s parole. Arlene is led out by two prison guards, and then released. Next, we see a woman in Arlene’s costume, with the same hair, seated on a chair. She speaks the first lines in the play, a monologue about terrorizing a neighbor boy when she was little. Thus, we are introduced to Arlene’s past self: “Arlie.” Throughout the entire play, both women are featured onstage simultaneously, with Arlie representing the brash, reckless woman, teenager, and child that Arlene once was. Arlene makes it a point, through the first half of the play, to insist that people call her “Arlene” now, as she has put that part of herself behind her. The nature of the play might make it confusing to follow what is happening between the two counterparts of Arlene. At times, it may be necessary to just sit back and let it all wash over you rather than try to understand exactly what is happening from scene to scene.

The contrast between the two leads was stark, and very interesting to me. Deanna Hope, who played Arlene, took on the role with a subdued kind of grace, despite the anger that was roiling just beneath the surface. It was easy to see that Arlene was holding herself back, eager to embody the sophisticated woman that she was hoping to become, now that she had served her time. Hope played the part with a singeing bitterness, always present, but barely ever manifesting itself, even when the script compelled her to do so. The performance was a perfect foil for Amanda Corbett as Arlie, who played the moments of Arlene’s life long passed with great spirit and energy, a veritable firecracker of passion and stubborn defiance. At first, the difference between the two actors seemed unbalanced to me, almost a mistake. I was wondering why the two weren’t working harder to mimic one another. Then, as the play went on and the script fleshed out Arlene’s story, I was fully engaged in their process.

Special attention must be given to Corbett, who played several stages of Arlene’s life, from early childhood to womanhood. She went from stage to stage with such adroitness that it made Marsha Norman‘s otherwise laboriously complex script easy to follow. I sincerely believed everything she did in a role that could easily be made cartoonish and trite. In a scene where Arlie lights her prison uniform on fire, I admired Corbett’s bravery, and in another where she, as a child, protests that her father did not sexually molest her, her terror was honest and heartbreaking.

The very first thing I noticed about this production was the set, designed by Nina Vought. It was broken up into two levels, the upper representing the prison, with multiple cells complete with toilets, sinks, and cots. The lower level was the apartment into which Arlene was moving, with a fully functioning kitchen, a bed, and a door leading to a dingy pink toilet. Garbage was strewn about the apartment, and the gritty realness of the entire picture played nicely against the dream-like quality of the script itself. I felt thrust into Arlene’s life, there with her in the depressing little hovel that was to be the place where she would rebuild her life.

Nina Vought also designed the costumes, and I appreciated the authenticity of both the uniforms of the guard and the prison uniforms. She also dressed all the actresses in a very unflattering way, which I actually found very appropriate. I was drawn to the humility of the women portrayed because of their frumpy clothes and undignified bearing.

Two other actors I took special notice of were Michael Calacino as Bennie Davis, a prison guard who takes a liking to Arlene, and Trayven Call as Carl, Arlene’s former pimp. Calacino played Bennie as the typical martyred “good guy,” the man who doesn’t realize that it’s possible for him to still think of a woman as a whore, even though he isn’t paying her for sex. It takes a lot of bravery to perform a rape scene (particularly as the rapist), but Calacino was able to accomplish this feat with deftness. As Carl, Call brought a much needed energy to the play, which lags in some points. I noticed, however, a problem that faces many actors who have never been coke addicts: Call overplayed his character’s addiction, which could be full of distracting sniffing and twitching. His constant pacing, though, was indicative of a troubled and frantic soul, and I appreciated it.

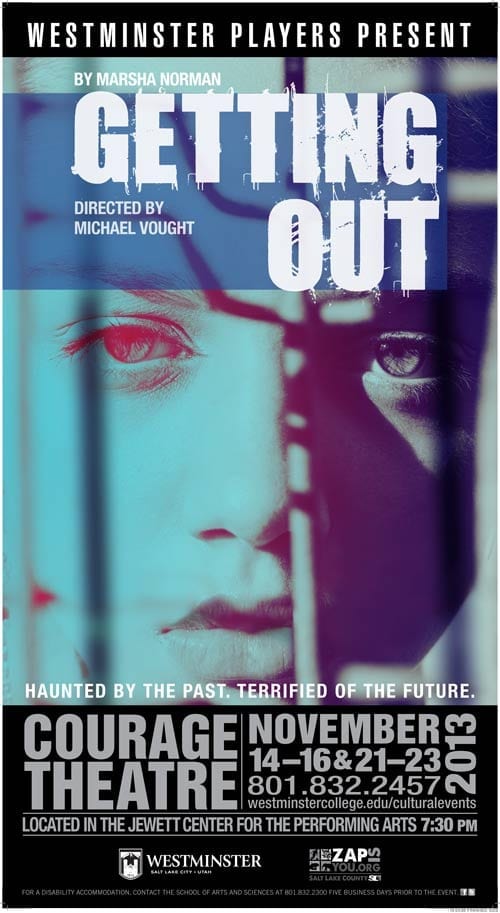

Michael Vought, the director, brings his cast together in an effort to deliver a very specific message to his audience: there is something inherently wrong in the justice system. His director’s note in the program made it plain that this was his goal, and he and his cast pulled it off. I felt drawn into the impossible situation in which Arlene finds herself, and I applauded her for her efforts to escape it, though it is evident, toward the end of the play, that she may never accomplish the destruction of “Arlie.”

[box type=”shadow”]Getting Out plays Thursdays through Saturdays at 7:30 PM at the Courage Theatre in the Jewett Center for the Performing Arts on the campus of Westminster College. Tickets are $10. For more information, visit