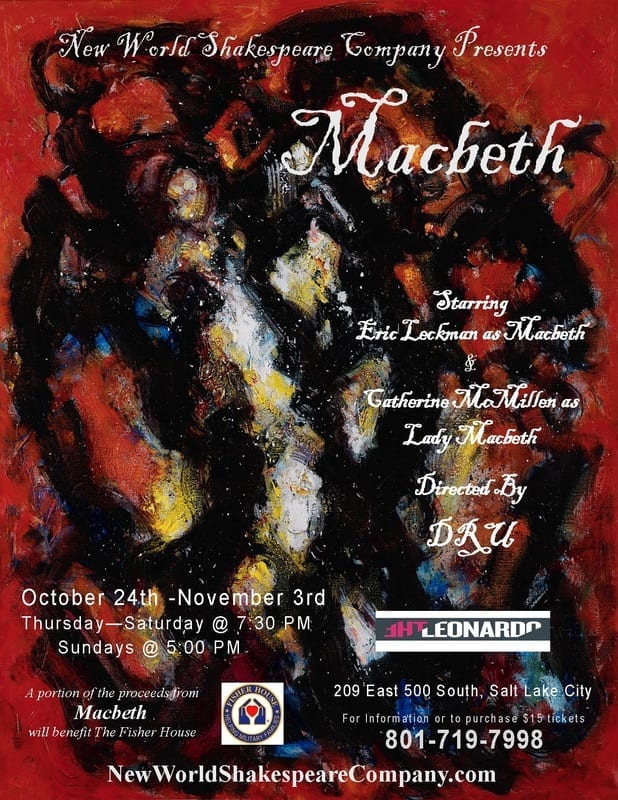

SALT LAKE CITY — The Leonardo, called a “contemporary science, technology, and art museum,” hosted New World Shakespeare’s modern Macbeth this Halloween season. Directed by DRU, New World Shakespeare set their Macbeth in what seemed to be a post-nuclear wartime. Most characters carried swords or knives, but a few had crossbows and guns. Some wore modern-day dress, like Lady Macbeth, while others’ outfits were more inspirted from the past or from a specific culture, such as the witches and Hecate. Design elements reminiscent of both past and present combined to create this hard-to-place setting and time: could have been present-day, could have been future. The program clarified, “Our production is set in the near future following the collapse of society. There are virtually no governments or technology left, and weapons and supplies are scarce.”

The production took place in The Leonardo’s third-floor auditorium, a venue probably designed for events like lectures and recitals. The company did a decent job using the space, with scenes taking place both on the stage and the large space of floor in front of the stage. However, much of the action that took place on either side of the floor was difficult to see, and scenes when action happened on the ground were just about impossible for anyone but the first few rows of audience members to see. The stage was left bare through most of the play, and that combined with inexperienced actors made it difficult to know the setting of each scene. Scene transitions dragged, which was odd because of the lack of scenery. Much of the pace, again most notably during the first half of the play, consisted of bodies standing around while one actor delivered his lines. An actor would speak, there would be a pause, and then another actor would speak, a pause, and so on.

I was astounded at the number of cast members: 31! Unfortunately the majority of them didn’t seem at all natural on the stage and made character relationships and scene settings hard to place. Leticia Minharo as Banquo struck me as one of the most comfortable actors onstage. Her relationships and conflicts were clear, and her character was strong even after death. I was also floored by the gripping performance of the Porter, played by DRU, who was only onstage for a brief but fervent monologue. He, also, was by far one of the most experienced actors on the stage, and had my attention from the moment he stepped into the light. I would have loved to see more of him. Jeff Stinson played a passionate, tough Macduff whose emotional levels astounded me. When he discovered his family had been murdered, I felt his sorrow in my bones. At one point Macduff says, “Blunt not the heart, enrage it,” and he absolutely did. He went from shock to sorrow to absolute rage in a monologue that had me on the edge of my seat.

And then there were the Macbeths. I found myself continually confused at their relationship: whether they had any affection for each other, whether Lady Macbeth was manipulating her husband, and later whether Macbeth was abusive to his wife, why they never touched, and so on. Perhaps it was the intention of actors and director to change the relationship so drastically during the course of the show. If so, they succeeded. In the first half, Lady Macbeth (Catherine McMillen) definitely came across as the one in control, while Macbeth (Eric Leckman) seemed weak and terrified. A few scenes after Duncan’s murder, though, Macbeth suddenly became intensely confident and aggressive. Both actors grew on me as the play progressed. I had mostly written off McMillen until the second half of the play, when Lady Macbeth falls prey to guilt and insanity and delivers her famous scene while trying to clean long-washed-away blood from her hands. She was mesmerizing in that scene, and I loved the old sink that was wheeled in front of the stage for her. It created an eerie picture. Macbeth, likewise, grew in strength and fascination as the play progressed. I found myself liking him much more as a ravenous villain than the timid creature he’d been before.

The sound design, by Danny Wood, flitted in and out behind the action, usually filling the space during scene transitions. I enjoyed the brief moments when background noise or music highlighted the action, but many times sound came on and off in the middle of a scene and tended to distract from the tone of the moment. At the end of the show, though, the action and music finally came together: hard rock perfectly underscored the Macduff and Macbeth face-off. Actors faces were often shadowed by a lack of front lighting. I’m sure this was a weakness of a space, as mentioned before, not designed for theater. Even so, there were some great lighting moments, designed by David Brunner. I loved how the Macbeth’s dagger shone during his “killing Duncan” monologue, reflecting from the single spotlight that lit the actor. It made for an ominous, withdrawn scene. I also loved the way the witch’s cauldron (a trashcan) glowed during their big scene. I found it interesting how the costumes, designed by Anna Marie Coronado, were varied at the beginning, with touches of red worn by those who would murder. As the show went on, though, color wore away and by the end everyone wore tans, neutrals, and browns, as if to imply the increasing difficulty of distinguishing the bad guys.

At any rate, New World Shakespeare’s production exposed more people to one of Shakespeare’s great tragedies, but this wasn’t my favorite Macbeth. The production could have used another week or two of polish before it was truly ready for the stage. The end was jumbled, and the last lines were lost in the chaos of 31 actors onstage. After the bows, the actors met onstage for a final picture: all crowded around Macbeth, spotlit in the center. Leaving the audience with that last powerful picture was a great move and somehow redeemed the chaotic ending.

[box type=”shadow”]New World Shakespeare’s Macbeth closed on November 3, 2013. For more information visit www.newworldshakespearecompany.com.[/box]