SALT LAKE CITY — I sat riveted through the question and answer session at the conclusion of Kultar’s Mime, listening to co-composer Sarbpreet Singh and the five person ensemble cast add perspective and context to the story I had seen unfold. “As hard as the story is to tell and to experience,” said Singh, “the story is uplifting. There is hope. A tremendous amount of hope.” His was a message I needed to hear, having just experienced the horrors of the 1984 pogrom against the Sikh residents of Delhi as told from the perspectives of four surviving children. One young boy, deaf and mute, was saved only because of his physical inability to scream at the horrors he saw. A nine year old girl held the hand of her dying father as he burned to death. A teenage Sikh girl had her honor stripped from her by a gang of offenders, while the final story told of a young man who watched the rape of his aging mother.

Told through two poems, In the City of Slaughter by Haim Bialik and Kultar’s Mime by an unidentified young Sikh poet, Kultar’s Mime was performed on a nearly empty stage in the Leona Wagner black box against a backdrop of chilling paintings by Evanleigh Davis. As I entered the space, I was welcomed and invited to walk into the performance space to view each painting and take pictures if I wanted. I also received a content warning that the performance would include both physical and sexual violence, and that I could leave the space at any time if I needed. As I studied the intensity of each painting, the strong colors and subtle details, I found it difficult to rest my eyes on the faces of the 1984 victims. I settled instead on the far left painting; a tree that seemed to be bleeding.

The performance began with a single word. Sydney Grant, the same woman who had welcomed me into the space, took the stage in a narrative role, commanding the audience simply to “arise.” She allowed silence to hang as I debated whether her command was literal, finally continuing into the opening strains of In the City of Slaughter. I noticed several details as she spoke, noting first her crisp diction, second the frequent alliteration embedded in the text, and third a pencil sticking out of her bun. Each detail would prove to be important throughout the production. As the other ensemble actors took turns presenting the poem, narrating their own characters, or delivering poetic dialogue, I was relieved to never have to strain to catch a word. I was entranced by the poems themselves, hanging on each instance of consonance or assonance, feeling the forward motion of the narrative enjambment. And I found myself relieved each time Grant would pull the pencil from or carefully replace it in her bun, knowing an intense moment had drawn to a conclusion, and I could resume breathing for at least a few moments.

Despite the beauty in the poetry itself, the five actors delivered it with varying degrees of success. When Ben Gutman spoke, I felt the constraints of rhyme and meter fade away, and I was able to focus wholly on the meaning. Rose Fieschko and Cassandra DeMarco nearly matched Gutman’s intensity when delivering the dialogue of an assigned character; however, when their lines swayed more toward narration, the rhymes jarred my awareness out of the story and uncomfortably back into the theater. Occasional synchronized movements of the ensemble had a similar effect. When the text was punctuated with a sharp, choral movement, I had difficultly relating to the artistically dramatic movement. The singular physical movements of the characters were also inconsistent at times. This was most apparent when the four children of Delhi assumed a frozen position. While those of Ross Magnant, Fieschko, and Gutman mirrored movement found in real life, DeMarco’s posture felt contrived and posed, her back arched like that of a dancer.

Perhaps most disorienting was the frequent transition from outside narration to self-aware narrative to dialogue made frequently by Magnant, Fieschko, Gutman, and DeMarco. Unlike Grant whose pencil made the transitions smooth and obvious, the other characters had no such device. I enjoyed each of these actors most when they had put on a small costume piece to become an assigned character. Fieschko shone in her portrayal of a precocious young girl in pigtails, embodying the spirit and spunk of nine-year-old girls worldwide. As DeMarco nervously picked at her arms, she effortlessly conveyed her deep anxiety. Magnant delivered one of the moments I remember most from the evening, narrating his own desire to scream and displaying his mute inability to do so. Somehow, removing the costume piece to step outside the story was not extreme enough for me; I had trouble leaving the character behind.

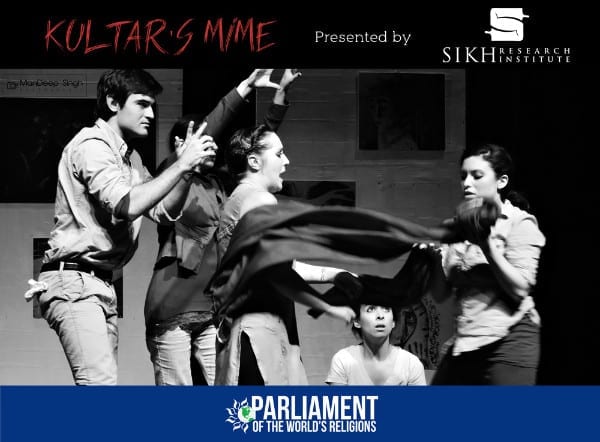

J Mehr Kaur, credited with both composition and direction, handled the violence of this production in a clever and tasteful manner, transferring the violent acts to the victim’s red headscarf. Whenever the story told of physical or sexual violence, these acts were mimed in relation to the scarf while the victim told his or her story nearby. While I still felt each act deeply, this careful portrayal of violence allowed me to remain physically and emotionally present to hear these important stories. As was later discussed in the question and answer portion, theatre is one of the most poignant art forms; to see such violence live before me, augmented intentionally by the voices, movement, lighting, and music brought me right to the brink of what I was prepared to handle.

An important question was raised in the question and answer segment, “Why, 31 years later, are you still choosing to talk about this?” I sat there stunned, floored at the realization that at 34 years old, I am only six years younger that the nine-year-old survivor in this story. I wondered why, 31 years later, we aren’t talking about this more. As Sarbpreet Singh stated, “This is not a story about Sikhs or Jews. It is a story about the cycle of violence that humans can’t seem to break. But on the flip side, there is compassion.” He went on to remind the audience of the dramaturgical note included in the program, “It tells a story of human suffering and courage, reminding us that in the end all innocent victims are the same, regardless of how they worship God and what tongues they speak.”

In closing, an attendee asked what the future holds for this as yet unpublished production. As I sat there considering the words like “compassion,” “hope,” and “inspiration,” that had already been mentioned, I did not expect the final response. Singh closed the evening by explaining that the ultimate success of this production would be that the young people who have seen it would be inspired to create art about difficult stories like this one. If, indeed, this work spurs similarly important works, I would be honored to take part in that audience.

[box type=”shadow”]Kultar’s Mime performed in Salt Lake City at the 2015 Parliament of the World’s Religions and stayed for one public performance at the Rose Wagner Performing Arts Center. The cast has presented this production at no cost to audiences across the world thanks to the generosity of sponsor cities and under the umbrella of the Sikh Research Institute. More information about this production can be found online at https://sikhri.org/km1984/.[/box]