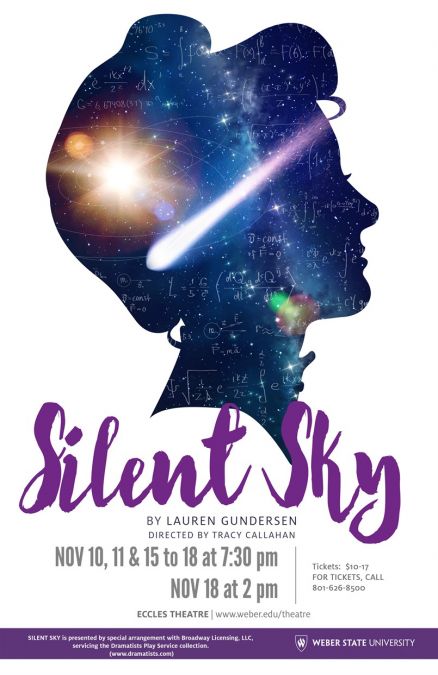

OGDEN — Silent Sky, written by Lauren Gunderson and directed by Tracy Callahan at Weber State University, blends the passion of astronomy with the theatrical passion of its performers. In Silent Sky, the central protagonist is Henrietta Leavitt, a real astronomer who, when relegated to the role of “computer” in the early 1910s because she was a woman, was able to research and accomplish significant developments in the understanding of space. Leavitt’s persistence proves very compelling and is as inspiring as the billions of galaxies that Leavitt’s accomplishments allowed science to study.

In Silent Sky, audiences who are readily exposed to the names of many male astronomers are introduced to the women whose calculations and accomplishments are only less well-known due to their sex. These women — Henrietta Leavitt, Annie Cannon, and Williamina Flemming — are recreated on stage in performances as bright as the stars. Though limited to the role of human computers transposing data and calculations collected by men at Harvard Observatory in the early twentieth century, the production is resolute in elevating their accomplishments to the public sphere. Weber State’s production draws such charm, eloquence, and even elegance in honoring the humanity of these women and their persistence in working beyond the earthly prejudices of their time.

The acting and characters are central to the joy of Silent Sky. The central three women astronomers are the delight of the production. Lily Hilden plays Henrietta Leavitt and is effortlessly convincing in presenting Leavitt’s intelligence and enthusiasm as an astronomer. Hilden then effectively manages the joy of Leavitt’s passion with competing distress and frustration with the sexism that limits Leavitt to the task of a computer (a person who performs mathematical calculations for a senior scientist). This is most apparent at the end of the first act as Hilden performs a monologue describing the discovery regarding variable stars and their periods of brightness, recognizing that there is music in their pulsating brightness. This discovery led to what would be Leavitt’s Law, an “astronomical yardstick” to measure the universe. While the technical details of such astronomy are dense, Hilden uses well-written dialogue to transpose the meaning effectively to the audience. It is clear in Hilden’s performance that this discovery was critical and meaningful, even if one has never heard of variable stars before. Hilden’s performance is fully realized and gives layers and humanity to a woman who outwits limitations and proves worthiness as an astronomer.

M Rayburn as Annie Cannon projects authority and composure to contrast Hilden as Leavitt’s youthfulness. Rayburn delivers a sense of leadership and competence that also brings a certain charm to this astronomer group. Madison Grissom as Williamina Flemming carries the lilting Irish humor of the character well. Every delivery from Grissom was a zinger that brought laughter and a smile. Both Rayburn and Grissom have terrific chemistry as co-workers and feel so relatable in their relationship. This was particularly true in their introductions which served as an entertaining delivery of each other’s significant achievements at the time. The women’s performances is lovely, as they move the progression of these characters as a trio of ambitious women brought to unity in their goals throughout the show. With the addition of Aisha Garcia as Margaret Leavitt (Henrietta’s sister), the four female roles of the production offer distinct representations of women of the time. And each performance gives layers to the importance of positive relationships across careers, family, and friends.

The fifth performer in the play is performed by Taylor Garlick, as Peter Shaw. The character is a composite of the male astronomers at the observatory and also serves as a romantic interest for Henrietta. While both Margaret Leavitt and Peter Shaw are fictionalized, having Margaret as a composite of sisters to create familial tension in the show feels more essential than what a fictionalized romantic interest offers. Garlick’s performance offers strengthens the story when Peter serves to illustrate how the male astronomers viewed their ambitious female computers. When Shaw dismisses Leavitt’s discoveries during a scene in the second act, the chill of negativity is palpable. In contrast, the romance feels unessential. Yes, it builds a personal stake in this dismissal, but it implies that the men could ignore the women’s contributions, even though there was a personal connection with them.

The set design and lighting are equally engaging and dimensional elements of the production while aiding, not distracting, the performers. The set, designed by Cully Long, has a unique element of the observatory’s domed roof overhanging the stage. The essence of the design shows the central focus of studying the stars, while also suiting the early 1900s period of the play. While Henrietta and her fellow computers are restricted to observing only the glass plates (because they are prohibited from using the telescope), they prove their skill in observing within these limitations. Likewise, the designers were required to representing an infinite field of stars within the limitations of the theatre space.

In a wonderful display of creativity, the beauty of the lighting is how the theatre creates Leavitt’s beloved star field. Lighting designer Jessica Greenberg lighting instruments above both the audience and stage to represent the stars. Used throughout the production, this “star field” is ever present and well incorporated into the action. This lighting element creates the theatrical environment that makes this production unique and fitting as a live production. The final scene of the show is a true theatrical delight in the way the design, performance, set, and staging come together in the space.

In Silent Sky, I felt as if I was meeting these extraordinary women on the stage drawn from the twentieth century to my own. No telescope is needed to visualize what this production offers: shining performances that recreate the brilliance of real-life female visionaries working in the field of astronomy. The characters’ joys, sorrows, frustrations, and persistence makes Silent Sky at Weber State entertaining and meaningful.

[box]Silent Sky plays Wednesdays through Saturdays 7:30 PM through November 18 and 2 PM on November 18 at the Eccles Theatre at the Val A. Browning Center for the Performing Arts at Weber State University. Tickets are $14-17. For more information, visit https://www.weber.edu/theatre/theatre-season.html.[/box]