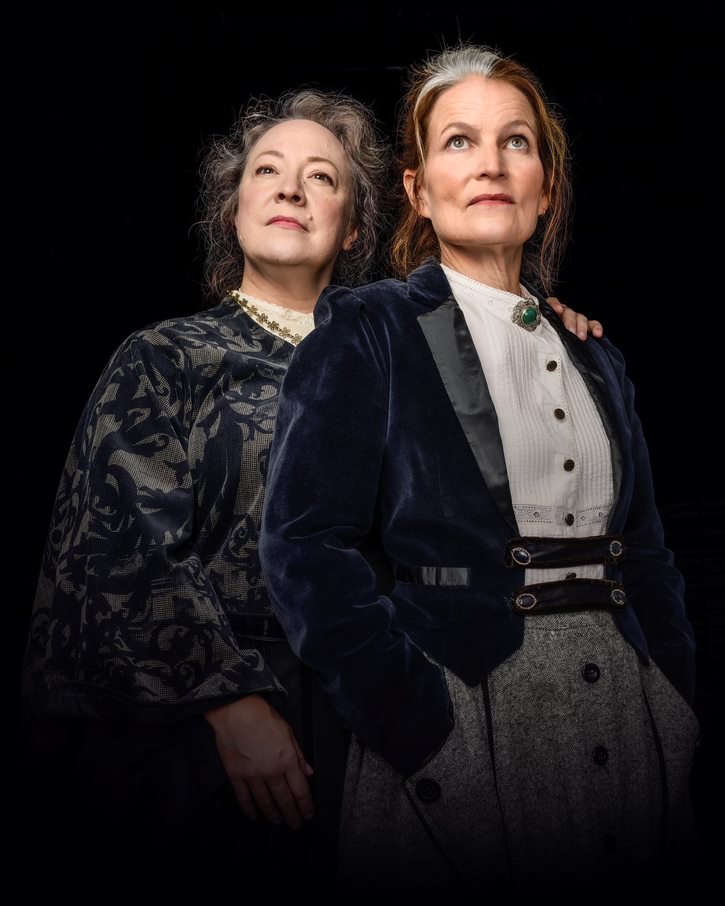

SALT LAKE CITY — The Half Life of Marie Curie, written by Lauren Gunderson, is a biographical story about Marie Curie (played by Stephanie Howell) and her significantly less famous friend Hertha Ayrton (played by April Fossen). Although it makes sense to craft a play around the well-known Marie Curie, she is in many ways, the least interesting of the two characters.

The play opens with Fossen on a stand beneath a single spotlight, reciting some of her accomplishments as an electrical-mechanical engineer. At one point she says, “There was a technical problem in the world, and I fixed it. You’re welcome.” Fossen’s wit carries the play and provides a stark contrast to the melancholy of Howell’s Marie Curie, who considers nature (and science) heartless and spends the bulk of the play longing for the married man with whom she had an affair.

The events of Marie’s affair are certainly true, and Gunderson uses the historical record as a jumping off point to talk about women’s rights and treatment in the late 19th and earthy 20th centuries. Because Hertha was also a suffragette (“Everything can be tied to suffrage!”), the issue of how women were denied access to scientific academies and considered property if married, is a consistent theme of the play. And much like The Sweet Science of Bruising, another play about women’s rights in the same era, I had to subdue my feelings that this vision of women’s history is really white women’s history. White American suffragettes famously excluded Black people, who did not get the full right to vote until the passage of the Voting Rights Act in 1965; and while both plays take place in Europe, there were certainly Indian women in England fighting for suffrage as well. Although the scope of The Half-Life of Marie Curie play is small, a major theme is women’s rights, and so it is difficult to disentangle my own identity (and knowledge and expectations) from the work. The Half-Life of Marie Curie felt more like white women fighting for other white women, and made me feel like I was not the target audience for this work.

Because of this, I did not emotionally connect with many of the characters’ struggles. Marie being in love with a married man felt both boring and juvenile; in a scene where Hertha and Marie are at the beach, and Hertha reads Paul’s letter to Marie, which reveals that his wife claims she is pregnant, prompting Paul to stay with her. Howell lets out this almost guttural scream and jumps into the ocean and nearly drowns. This portion, however, is technically enjoyable as there is a blue light shining down on her, underwater sound effects and Howell is moving in slow motion to imitate being underwater. It is a lovely moment created by director Fran Pruyn, who has a strong handle of the script and what drives the characters.

In fact, the play abounds with effective use of sound and lighting throughout. When Hertha comes to visit Marie in France, there is the loud rumblings of a crowd that she yells at as she passes. As the two of them talk, there is a moment where one of Marie’s daughters begins to play the piano and music plays (this happens multiple times). As Marie recounts her own story of how she works with radium, there is a type of clicking sound that she says only she can hear that emits from the chemical. Sounds of the ocean, seabirds squawking overhead, heart beat noises and more are sprinkled throughout the play helping to create a sense of place.

The best use of lighting (designed by Pilar I) and sound (designed by Mikal Troy Klee) is when Marie collects her things to take the train after Hertha and Marie get into a fight. There is a single green spotlight on her as she slowly dresses, with train noises playing in the background. In the past, characters standing on these single stands spoke dialogue, but in this moment, it was utter silence as she quietly leaves her friend behind. And then there is the sound of her heartbeat.

Even though both Howell and Fossen give solid performances, the script clearly prefers Hertha, and Fossen takes advantage of that. The character has a more compelling worldview; she is proud that her daughter is arrested for protesting for suffrage, and Hertha changes her first name based on a poem by Algernon Charles Swinburne. Indeed, she is the main driver of the play as she compels Marie to stay with her in England, and later she confronts Marie about carrying around a vial of radioactive radium. Howell plays Marie as a cold woman, fixated on what people think about her, childish in her obsession with Paul and wholly uninteresting. Like yes, winning two Nobel prizes in two different fields is interesting, but she only goes to the ceremony after being prodded by Hertha, and her holier-than-thou mentality as it pertains to science is revealed in an argument between the two.

The play ends with interesting factoids about both women that did feel illuminating; Marie invented portable x-rays for the war effort, and Hertha created fans to blow away chemicals being pumped into the trenches. And the script describes the actual events for both women up until their deaths. In this sense The Half Life of Marie Curie is really a great primer for anyone would be interested in the lives of two women who very, very much love science, research, and knowledge.

[box]The Pygmalion Theatre Company production of The Half-Life of Marie Curie plays Thursdays and Fridays at 7:30 PM, Saturdays at 4 PM, and Sundays at 2 PM through November 18 in the Black Box Theatre at the Rose Wagner Performing Arts Center (138 West 300 South, Salt Lake City). Tickets are $15-22.50. For more information, visit pygmalionproductions.org.[/box]