OGDEN — When I was thirteen, I was ecstatic to be cast in my first play, a local production of Guys and Dolls. I was cast as a waiter, but when the actor chosen to play Benny Southstreet failed to show up on the first day of rehearsal, I was promoted on the spot. This was my first time at the Ziegfeld Theater in Ogden, and it instantly took me back to that community theatre—a converted space, hand-painted flats, creative casting, and a local crowd. I remember it fondly as a lot of fun and a baptism by fire, but I have no illusions that it was very good. We should have been so lucky to have had our efforts coalesce into a show as full of life and verve as this Carol Madsen-directed production at the Ziegfeld.

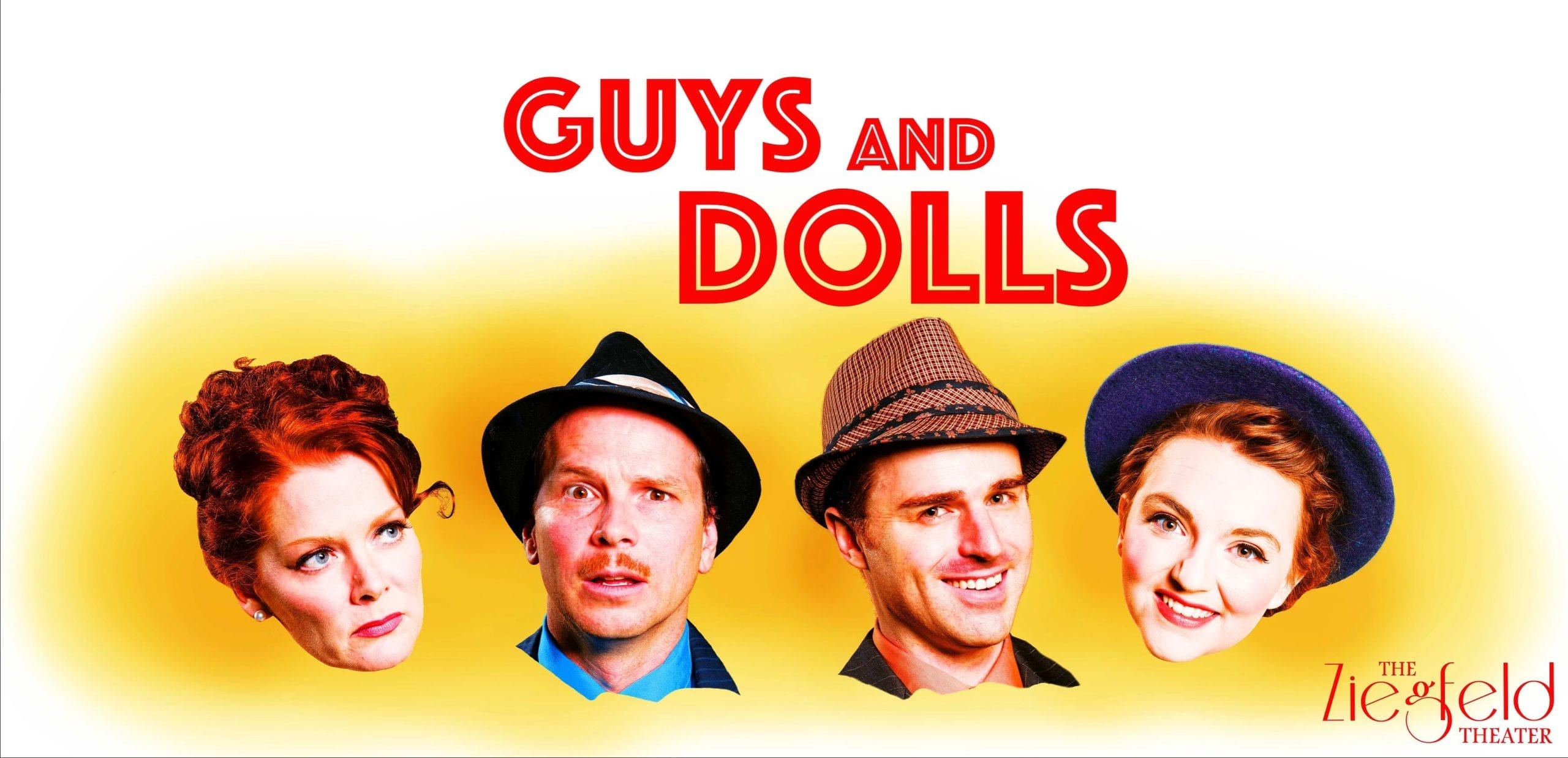

Guys and Dolls, with music and lyrics by Frank Loesser and a book by Jo Swerling and Abe Burrows, tells the story of two very different relationship paths. The first is the fourteen-year engagement of Miss Adelaide (played by Christie Stolworthy), star of the Hotbox nightclub, to Nathan Detroit (played by Nathan Sachs), the proprietor of the “oldest established, permanent floating crap game in New York.” High rollers are in town, and Nathan is anxious to cash in. But Adelaide is finally fed up with his crap game and excuses for putting off their wedding. Speaking of high rollers, relationship number two involves the “highest player of them all,” Sky Masterson (played by JJ Bateman), who finds himself caught up in a whirlwind romance with Sergeant Sarah Brown (played by Kacee Neff) of the Save-a-Soul Mission after making a bet with Nathan.

The technical design of the show is simple, allowing the material to take the spotlight. Aaron Linford’s set never changes. Its painted flats depict brick walls, urban windows, and a fan of cards and horse race ticket stubs to suggest the Runyon-esque atmosphere. I liked some touches, such as Adelaide gracing the queen of hearts or the shape of the card fan resembling a sewer pipe, but was less enthusiastic about others, such as the projections on the fan of cards and the windows. At the very least, the projections should be confined to the windows alone, as the vertically stretched images on the card fan were distracting. The fact that, more than half the time, the cards double what is playing on the windows compounds the problem. This is unnecessary and asymmetrical, not only because one is noticeably distorted and one is not, but also because they sit side by side at stage right and center, which doesn’t provide visual balance across the stage.

This distortion and imbalance in the visual department carried over into other technical areas. The music was not always in equilibrium with the actors’ voices (although the muddy house speakers did help obscure the canned nature of the pre-recorded soundtrack a little). Sachs’s mic crackled with static in the early scenes. Though the vignettes in the title song were an interesting choice, they too often pushed the singers, Benny Southstreet (played by Austin Stephenson) and Nicely-Nicely Johnson (played by James Booth), into the shadows. The performances had their weaknesses too, and the cast doesn’t overflow with triple threats. Hardly a voice didn’t crack, and many a line was dropped, rushed, mis-timed, or drowned out by the underscore.

However, I had a great time. The company’s exuberance and commitment filled the space with energy, which I could feel even before the curtain rose. The chorus wasn’t always perfectly in tune, but their unison of spirit was electrifying. The choreography stretched their limits, but I couldn’t catch anyone doing it halfway. They left everything out on the stage. Sachs imbued Nathan with an appealing manic energy. Stolworthy’s choices told a million tales in subtext. Neff went for broke in Sarah Brown’s drunk Havana escapade. Brent A. Johnson’s Gilmore Girls’ Kirk-iness contributed to the mission’s small-town earnestness. And special distinction goes to Mejai Perry for throwing himself into the dual roles of Harry the Horse and a hotbox dancer with the same frenetic abandon.

I have seen more than my share of cold, emotionless equity productions in this state. The Ziegfeld’s Guys and Dolls is the opposite of that, in the best possible sense. The group chemistry was so palpable it came out in their sweat. This is true community theatre. A group of enthusiasts with a fog machine decided to put on a show, and I wish they’d commercialize whatever fluid they’re filling it with, because it had me charmed from the beginning.

[box]Guys and Dolls plays at The Ziegfeld Theater (3934 S. Washington Blvd, Ogden) Fridays and Saturdays through November 4 at 7:30 PM, with a matinee October 28th at 2:00 PM and a Monday evening performance October 30 at 7:30 PM. It will then play Park City’s Egyptian Theater (328 Main Street, Park City) November 17–19, 21–22, and 24–25 at 8 PM. Tickets are $17–19 in Ogden and $29–45 in Park City. For more information, visit theziegfeldtheater.com.[/box]