LOGAN — One hundred and thirty-eight years after its 1879 New York City premiere, Gilbert & Sullivan’s The Pirates of Penzance still retains a prominent place in American popular culture. This is borne out by the many references to it in such diverse contemporary media as Aaron Sorkin-scripted dramas, Lin-Manuel Miranda’s Hamilton, web comics, and even marketing for tentpole animated feature films. Moreover, it is that rare property that can be (and is frequently) produced in almost any venue, from professional opera companies to community theatres—ensuring that it will continue to be a goldmine of allusion, quotation, and parody for the foreseeable future. Taking such flexibility and longevity into account, it should come as no surprise that a comic opera that has wielded considerable influence on musical theatre over the years should feel so at home at Utah Festival Opera & Musical Theatre. Indeed, it is almost as if The Pirates of Penzance were the embodiment of the ampersand in the company’s name.

Show closes August 9, 2017.

The popularity of Gilbert & Sullivan works has played a part in the growth and development of amateur theatre in the United States since before the turn of the century. However, try as they might, these productions usually can’t fully realize the score as it was written. As a result, the comedy and social satire play better than the musical satire, obscuring the fact that Pirates at times transcends the blurry line between opera parody and genuine contribution to the genre. A look at the 1983 movie version starring Kevin Kline bears this out. People’s fondness for it is almost never because it has instilled in them a particular love for the music. The comedy resonates, but the grace and pathos of Sullivan’s more lyric passages are lost among the synthesizers and lower keys for Linda Ronstadt. So while I am not a snob about reinventing canonical properties, there is always something to be said for a company that can both deliver the well-loved humor as well as do the score justice. Fortunately, UFO&MT and director Brad A. Carroll have managed to do exactly that.

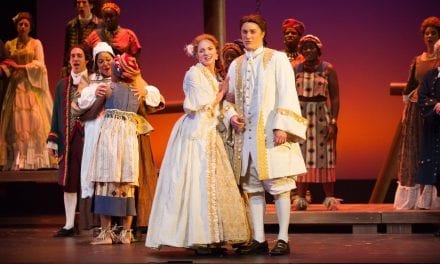

The Pirates of Penzance tells the story of Frederic (played by Edward Brennan), who, due to a mistake by his nursemaid, Ruth (played by Cabiria Jacobsen), was apprenticed as a boy to a pirate instead of a pilot. The curtain rises on the pirate celebration as Frederic, at twenty-one, will shortly be freed from his indentures. After explaining to the Pirate King (played by Ezekiel Andrew) and his shipmates why it is that they can’t “make piracy pay” (mostly because they are too tender hearted), Frederic reveals that, though he loves them dearly, it will be his duty to seek their annihilation as soon as he departs their band.

Frederic leaves for shore, where he immediately meets and becomes engaged to Mabel (Olivia Yokers), one of the many wards of Major-General Stanley (Curt Olds). The pirates soon follow and make designs on the Major-General’s other daughters, but are thwarted by Stanley’s cunning. Frederic rounds up a force of policemen, led by their sergeant (Kevin Nakatani), in order to destroy the pirates; but the Pirate King and Ruth use Frederic’s devotion to his sense of duty to manipulate him into rejoining the pirate crew before the final confrontation.

The orchestra, conducted by James M. Bankhead, and the first-rate singers give the score its rightful prominence. I was thrilled with the vocal performances of Brennan, Yokers, Andrew, Jacobsen, and Nakatani. For example, Ruth’s low G’s at the ends of her phrases in “When Fred’ric was a little lad” are usually glossed over or spoken, yet Jacobsen leaned into them with relish. Often, in “Oh, is there not one maiden breast?” one can see the high B-flat (which is written as optional, but isn’t really) coming a mile away as the actor’s anticipation escalates the nervous tension in his voice and posture. Yet Brennan carried it off with the unceremonious ease of someone not aware of the feat or its effect on the surrounding “bevy of beautiful maidens.”

Sometimes, lesser singers are incapable of conveying Mabel’s tendency to show off because they cannot execute passages such as the melisma when she first enters, leaving her character the lesser for it. Not only did Yokers sing that melisma into submission, but she deserves special praise for insisting on a schwa in the last syllable—rendering it correctly as MAY-ble instead of May-BELLE. It was likewise refreshing to hear, in Nakatani, a Sergeant of Police whose voice might credibly be successful at charging someone as formidable as Andrew’s Pirate King to yield, especially given the police force’s general predilection for cowardice.

But perhaps the greatest burden of expectations falls on Olds, as Major-General Stanley, who is entrusted with one of the most parodied theatrical sequences of all time. In fact, such is the legacy of the patter song “I am the very model of a modern Major-General” that it is the only number from the Gilbert & Sullivan trifecta of H.M.S. Pinafore, The Mikado, and Pirates to have its own Wikipedia page. It’s also a setup for caricature. Fortunately, Olds gives the necessary attention to both physicality and character business to make Stanley more than just excellent elocution framed by facial hair.

Robert Little’s set consists of little more than painted backdrops and platforms, but this isn’t the kind of show that demands technical wizardry. To the contrary, it feels more at ease without it, a fact that director Carroll shrewdly uses to the show’s advantage. I have been frustrated with sluggish scene changes at UFO&MT in the past, so I appreciated how Carroll played this tendency for laughs. In the only scene change that matters (because the other is during intermission), the interstitial music ended and the lights came up (twice) before the pirates finished redressing their pirate ship as a rocky beach. Caught unprepared each time, they froze and looked out at the audience while one gestured frantically to the conductor to play the music again. Not only was I amused by this hint of self-awareness, but it also provided some nice symmetry with a scenery gag during the overture that I won’t spoil for you.

However, there is one visual element that needs immediate attention. The green, ghostly, spiderweb-like light projected onto the skull of the pirate ship’s sail (and over the mast) is tonally and aesthetically inconsistent with the rest of the production design. It made me wonder if a Death Eater had escaped from a Harry Potter movie and cast a dark mark over the ship. So unless Carroll decides to kill someone off in the first scene, the light has got to go.

One recurring problem at UFO&MT is its lack of depth on the acting bench. The good news is that the broad humor of Pirates makes this easy to hide most of the time, though there were some comic timing miscues and the occasional talking through a laugh (ahem, Pirate King). However, my main critique in this regard has more to do with one specific directorial choice. Though Brennan acquits himself well in what is a conventional portrayal of Frederic, I wish Carroll had instead used the character as more of a straight man to his shipmates’ “credulous simplicity.” The general silliness of Pirates needs a foil to be most effective: someone to provide the theatrical equivalent of a Jim Halpert mug to the camera or a Bob Newhart deadpan.

This effect is then heightened when the straight man finally succumbs to the absurdity surrounding him. Much like when Michael Bluth exhibits the occasional Bluthiness in Arrested Development, Frederic’s devotion to duty must eventually culminate in showing that, for all his better sense, he isn’t that different from the pirates after all. That is why he rejoins them. Not so much because it is his duty, but because his fanaticism is matched only by the pirates’ refusal to ever attack an orphan. The truth is that Frederic and the pirates deserve each other. A more deliberate negotiation of their symbiotic relationship would enhance both comedy and character.

But on balance, these flaws are easy to overlook alongside how well this version of Pirates manages to bridge both humor and musical sophistication. It obscures UFO&MT’s weaknesses and highlights its strengths. It’s a buoyant incarnation of what is arguably the greatest of Gilbert & Sullivan’s works, and certainly the best-sung production of it that you are likely to see in the state.