SALT LAKE CITY — Utah Repertory Theater Company’s Amadeus (written by Peter Shaffer, directed by JC Carter) tackles some complicated subjects while also being hugely entertaining. This is the 1999 revival of the show, based on a rewrite of the script done by its author after the 1984 film was released (which was based on the original 1979 script). This is not a rehash of the movie—there are substantial differences between this production and the film. Those differences, plus the benefit of seeing excellent live performers work their magic with the material, make this production well worth your time whether you’ve seen and loved the movie or not.

At its core, Amadeus is all about relationships. It examines relationships between the characters on stage, and it examines the relationships between the characters and God. (“Amadeus” literally means “Love God” and is the middle name of the famous composer Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart.) But it also pays respect to the historical figures at the play’s center and reverences the music that is discussed throughout the production. The two main characters—Salieri and Mozart (played by Roger Dunbar and Geoffrey Gregory, respectively)—each contribute to the themes and subject matter of the play, sometimes in deliciously contrasting ways.

Dunbar is incredible as Salieri, the show’s main character and narrator, who becomes extremely jealous of Mozart’s talent and thwarts to destroy him. During much of the show, Dunbar is simply monologuing—going from thought to thought seamlessly, truly conveying the madness of a man bent on stopping his rival. Each time Dunbar speaks, he emphasizes just the right words, almost chewing on the name “Mozart” whenever he says it, in a way that conveys both contempt and utter admiration, delivering a complicated performance of a conflicted man. At the same time Dunbar is wrestling over his relationship with Mozart, he is simultaneously wrestling over his relationship with God. Dunbar does this effectively, slowing down when speaking to give emphasis to important phrases in the script, such as when he is contemplating committing some truly vile acts. “What about virtue, fidelity, and all of that?” he says to himself and the audience, pondering the path he is about to take. Then, with a shrug, he says, “I couldn’t think of that now.” Dunbar’s methodical delivery of the line demonstrates how quickly his fleeting desire to do what is right is drowned out by his desire to be the best.

Gregory is fantastic as Mozart. For a time, I was more captivated by Gregory’s Mozart than by Dunbar’s Salieri (which I’m sure the character of Salieri would find ironically appropriate due to his own obsession with Mozart), as Gregory’s presence on stage nearly always felt like a lightning strike of energy. In part, the power of Gregory’s performance was enhanced by the staging directions and the supporting characters. When Mozart is in the room, all eyes are drawn to him, while Salieri is often confined to a chair in the corner, or turned away from the action. Salieri becomes only an afterthought in the presence of Mozart—despite the fact that Mozart becomes the only thing that Salieri can focus on.

By the end of the production, however, I was hanging on Dunbar’s every word, enjoying the struggle being conveyed by his performance more than anything else in the production. When Dunbar, as Salieri, talks about the importance of music, particularly of the perfection Salieri sees in Mozart’s music, I am convinced of his sincerity. There is one particular point in the play when Salieri pores over one of Mozart’s pieces, and as he reads the notes on paper, the music comes to life over the speakers. Salieri speaks of the single-noted oboe delivering a haunting melody, followed by the strong clarinet, and as he describes each instrument and movement in synchronicity with the actual music, I feel as if I am inside Salieri’s head, discovering Mozart’s music for the first time.

The other actors do a remarkable job in their supporting roles. Greg Carver as Emperor Joseph II brings a comedic lightheartedness to his scenes. His delivery of an oft-repeated line, “There it is,” is always perfectly paced so that it nearly always brings a laugh. Merry Magee as Constanze Weber, who becomes Mozart’s wife, delivers a convincing performance of a woman who believes in Mozart’s genius and fights for him against his oppressors, while at other times she challenges Mozart when his arrogance in his own talent gets the better of him and contributes to his family’s suffering. Lindsay Marriot as Venticella and Dallon D. Thorup as Venticello function as a chorus, reporting to Salieri and providing exposition to the audience. Though their particular roles did not lend themselves toward being overly memorable or captivating, they performed their functions well with energy and determination. The remaining supporting cast likewise carried commendable performances, fulfilling lesser but important roles that drove the story. Many of these actors had to learn phrases in French or Italian, and they pulled them off without a hitch. Even when I could not understand what was being said because of extended non-English lines, I was captivated by the emotion behind the actors’ words.

In addition to the actors, the other people who worked on the play contributed admirably. The costumes by Nancy Susan Cannon all look period-appropriate, but have bright colors to keep them interesting. Mozart’s wig—a bright white fluffy concoction that helps ensure all eyes are drawn to him when he is in the room—was also standout piece (credit to wig designer Cindy Johnson). The set (scenic designer Allisyn Thompson and set designer Carter) is busy without being overly complicated. A beautiful period piano sits on one end, and this is used in many instances throughout the play. A maroon armchair sits on the opposite end—Salieri’s chair, where he skulks during much of the performance. Pictures line the wall at the back of the set, portraying the city of Vienna and some prosaic landscapes. A projection screen sits above the set, with slides that show occasional pictures of the city and occasional images of the title pages of Mozart’s various operas and scores.

The music in the play is genuinely captivating and beautiful. Anne Puzey (music director) and James Hansen (sound designer) aptly coordinated the music so that for the most part, it enhances the performances rather than overpowering them. During one early scene, Natalie Easter (who plays the part of soprano Katherina Cavalieri) sings to entertain guests. The notes are powerful, but she keeps them quiet enough so that Salieri’s monologue can be heard during the song. Later, the same actress is let loose as she delivers a convincing operatic performance during a scene without dialogue.

The only part where I felt the music was a distraction came toward the end of the play during a climactic scene between the show’s two stars. The blaring music ended up distracting from the performances and even drowning out some of the words at points. I found myself relieved when the music finally died and a spotlight held the two main actors in a small space at one end of the stage while they confronted each other. The scene was effective because the silence was such a contrast to the music that had preceded it. That scene is also helped by the lighting design (Carter), with the spotlight bringing the main actors into focus for the audience.

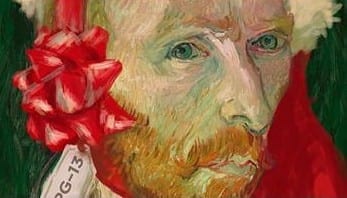

All of the show’s elements are ably tied together by the show’s director, JC Carter, who introduced the show (and the rest of the season) with a contagious excitement. His positive influence on this production can be easily seen. The material could easily disintegrate if not handled carefully into a depressing or overly dark tragedy on one hand or pure unintentional comedy on the other. Instead, the production cohesively blends the tragic elements (i.e. suffering and death) and comedic elements (like the immature ramblings of Mozart) to make the audience laugh one minute then feel pity the next. Amadeus is an excellent production for philosophers, musicologists, historians, and pretty much anybody who wants to have a good time (just be aware that the show has some adult situations; I would rate it PG-13).