When I was eight years old, I was a huge fan of hall of fame quarterback Steve Young. My family lived in northern California, and everything he did was the epitome of cool for me. I wanted to drive the cars he drove in commercials, throw left handed like he did, and imagined him coaching me when I would pass footballs at school. I once got to meet him as a star-struck child where he signed my jersey right on my back. I never had that kind of fervor for a theatre maker, but it was clear reading Paul Salsini’s memoir Sondheim and Me: Revealing a Musical Genius that Salsini had that same youthful admiration for Stephen Sondheim, which led him to found The Sondheim Review (a periodical dedicated to Sondheim’s work) and eventually write this book. After all, how often do you get to be in regular correspondence with an icon?

I would not describe myself as a Sondheim aficionado. I could have only named three musicals (Sweeney Todd, West Side Story, and Into the Woods) written by the revolutionary and complex composer. I knew he was famous for multifaceted and striking accompaniments that are often dissonant from his melodies. But I could not have told you much about the man himself, his creative process, or what he thought about his own work. Fortunately, I found the read enlightening, engaging and accessible as a fair weather Sondheim fan.

I would not describe myself as a Sondheim aficionado. I could have only named three musicals (Sweeney Todd, West Side Story, and Into the Woods) written by the revolutionary and complex composer. I knew he was famous for multifaceted and striking accompaniments that are often dissonant from his melodies. But I could not have told you much about the man himself, his creative process, or what he thought about his own work. Fortunately, I found the read enlightening, engaging and accessible as a fair weather Sondheim fan.

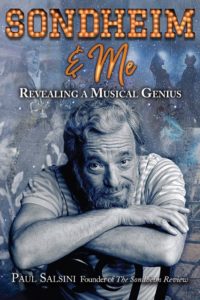

Sondheim and Me is largely a chronologically ordered series of correspondence between Salsini and Sondheim, with Salsini’s reflections upon that correspondence. Salsini is a Milwaukee-based journalist whose appreciation of Sondheim’s work and his journalistic nature led him to reach out to Sondheim in 1984 about musical (that had never been produced at the time) called Saturday Night. The two exchanged intermittent correspondence for the next decade until Salsini expressed interest in compiling a more comprehensive record about Sondheim’s works, including interviews, play reviews, information about notable productions, and more. Sondheim expressed support for the project, and for several years he would read the quarterly magazine cover to cover, and would include notes about errors and omissions to be included in the next edition. The Sondheim Review, which went out of publication about five years before Sondheim’s November 2021 death, was a body of critical research and evidence of productions that serves as a historical record and academic archive of Sondheim’s work.

The book was a beautiful extension of what The Sondheim Review was intended to be: all about the work, not about the man. Yet, in that unpacking of the work, I began to see the personality and inner workings of the man himself. I loved reading his interview about the play Passion in which Salsini asks about Sondheim’s penchant for not wanting to “write the same show twice, that you want a challenge.” Sondheim acknowledges that fact and then dives into what made Passion challenging to write, including the fact that writing it did not bring him joy because the experience was so difficult. These are not the kinds of tidbits that modern audiences expect to hear when creators talk about their work. The insights like this were fascinating in the text.

I think this is what Sondheim die-hards will love most about the text. Readers get generous glimpses into the mind of a genius as he unpacks in candid ways his successes and follies (pun intended) in both process and product as a writer. It is interesting to read about productions that did not happen, how Sondheim worked tirelessly on fine details. What was unfortunate for me is that this text is not a comprehensive look into Sondheim’s creative process prior to 1995. Sondheim and Me really zeroes in on late-career Sondheim during the time Salsini was working as editor of The Sondheim Review. There are sections that explore Into the Woods, Gypsy, Assassins, and Company, but I would have loved more space dedicated to West Side Story, Merrily We Roll Along, and other important works from Sondheim’s career.

Salsini manages to reveal great things about the person of Sondheim and insights into his work and working process. I think a text like this is mandatory inclusion in the library of any Sondheim scholar or superfan who wants another deeper angle at understanding the musical luminary. It is not comprehensive telling of Sondheim’s life and work, but it is worth a close ready for those seeking to better understand Sondheim in his late career. After reading Sondheim & Me, I am certainly much appreciative of and engaged with Sondheim’s work. I have added several of Sondheim’s musicals to my playlists and feel that the book is worth reading a second time. While my lack of context about Sondheim did not diminish my enjoyment reading the book, I am not sure that it will engross a reader who are not already aware of Sondheim’s importance. For those who love theatre for the sake of theatre, however, Sondheim & Me will add immensely to the reader’s understanding of both the craft of playwriting and the mind of one of the most renowned creators of the 20th century.

[box]Sondheim & Me: Revealing a Musical Genius is written by Paul Salsini and published by Bancroft Press. For more information, visit https://bancroftpress.com/sondheim-me/.[/box]