CEDAR CITY — A 20th century American hero, Thurgood Marshall claims titles such as civil rights activist, the first African American Solicitor General of the United States, and the first African American Supreme Court justice. As a lawyer, Marshall’s most notable cases are Smith v. Allwright (outlawing racial barriers to voting for southern black Americans) and Brown v. Board of Education (which desegregated public schools across the United States). Set in a makeshift lecture hall at Howard University Law School, Thurgood at the Utah Shakespeare Festival follows the title character as he delivers a frank, brutal, and victorious recap of his life and trials as a civil rights activist and lawyer from 1933 to 1991. The script by George Stevens Jr. is an honest insight into the ongoing fight for racial equality in America.

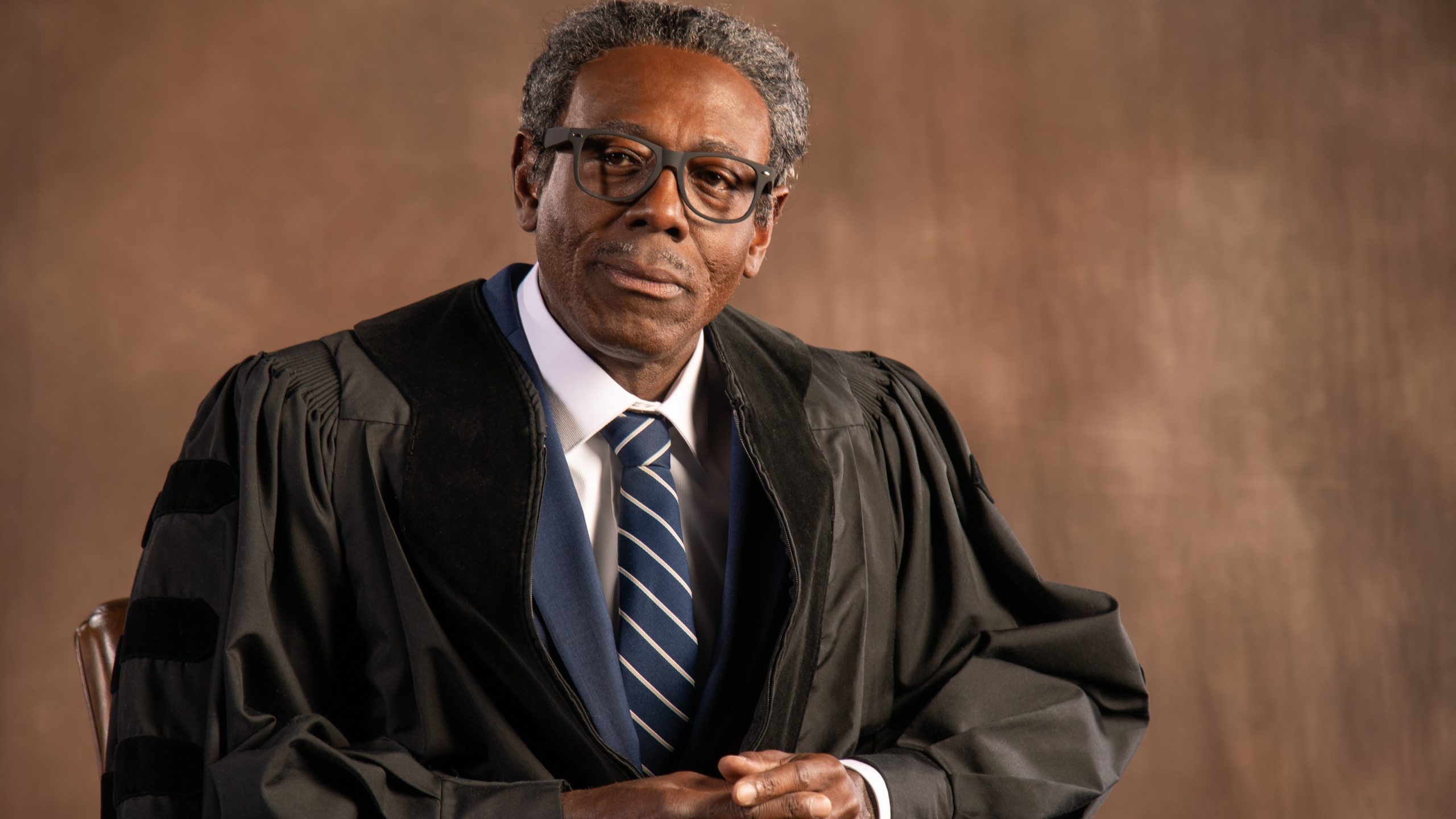

Derek Charles Livingston plays Thurgood Marshall in this solo show. Without pomp, and without a change in lighting or a pause in the pre-show Motown soundtrack, Livingston enters from the audience as an elderly, cane wielding, limping Marshall. The blue suit and square glass frames are styled wonderfully by costume coordinator Jeffrey Lieder. Livingston’s Thurgood Marshall is old, tired, but not frail. The set, by Richard Girtain, is sparse but effective: a podium on one side and on the other, a coffee table and sitting chair atop a simple persian rug. As Marshall settles in and pours himself a glass of water, a voiceover announces that the special guest lecture is now beginning. Livingston’s tone is low, slow, powerful, and prepares his audience for a moving story with monumental ups and gut-wrenching downs.

Almost immediately, Marshall ditches his cane and transports back to the 1930s as a young ambitious man in Baltimore, Maryland. Livingston proves himself a passionate storyteller with humorous impersonations and heart-breaking soliloquies. While his delivery is shaky in the first 20 minutes, Livingston eventually finds solid ground and demands audience interaction with lines like, “and that case was called . . .” with a spectator yelling, “Brown versus Board of Education!” This immersion is taken even deeper, as Livingston garners more and more emotional investment from me. As Livingston reenacts a courthouse victory, I erupted in applause.

Throughout the rest of the 90 minute play, I clapped, gasped, laughed, and cheered in reaction to Livingston’s tale. Livingston embodies Thurgood Marshall at different stages and places in life. Livingston shows Marshall as moody, stormy, passionate, funny, playful, broken, and as an unsure, then eventually imposing presence in the courtroom. Over the course of the story, Livingston subtly shows the passing of time with a limp, a hand-tick, a stoop, or a slightly lower and raspier voice until the character is finally back in the Howard Law School lecture hall in 1991. Thurgood Marshall’s life and Livingston’s performance equally earn every gray hair in Livingston’s wig.

The lighting by Jaymi Lee Smith helps Livingston travel in and out of memories, time, and impersonations, and clues the audience in to the emotional shifts in Livingston’s performance. Additionally, the projections on the “lecture hall screen,” designed by Chandler Oppenheimer, serve at times as an alternative set, and at times as a display for sepia images meant to evoke familiarity with the times and issues. The photo collage towards the end of the play is especially moving. The few sound effects (also designed by Oppenheimer), such as a blown camera glass, a courtroom gavel, or an electric guitar national anthem, are fun and surprising. While the sound effects do not detract from the play, Livingston’s skill as a storyteller may render them unnecessary.

Director Delicia Turner Sonnenberg helps Livingston bring Thurgood Marshall back to life as a storyteller that rivals the ancient Greeks. The entrance, the water breaks, and the changes in manner and tone all lead me to believe I was not just witnessing a lecture by esteemed guest speaker Thurgood Marshall, but I was also traveling through time and watching his life from troublemaking schoolboy to associate justice of the Supreme Court.

On a personal note: I grew up in Louisiana. My brother attended a private school founded as a segregation academy after Brown v. Board of Education. I remember when the first black students were admitted to his school. Ruby Bridges, also a Louisiana native, celebrated with us and the public schools in that district hosted reenactments of Brown v. Board of Education. It was fun to play make-believe as a child without understanding the depth of the circumstances. Thurgood at the Utah Shakespeare Festival brought me to tears and then to thunderous applause with the in-play victory of the famous court case. I clapped with Thurgood Marshall in 1954, I clapped with my community in 1999, and I clapped with audience members in 2022 for the continued remembrance and fight for equality that I saw in this moving production of Thurgood.

[box]The Utah Shakespeare Festival production of Thurgood plays various dates and times in the Anes Studiot Theater on the campus of Southern Utah University. Tickets are $49-59. For more information, visit bard.org.[/box]