SALT LAKE CITY — Black lawyer Henry Brown tells his potential client something to the effect of, “A black man can talk about race, a white man can not.” I have felt similarly while trying to set out my response and criticisms to David Mamet’s Race by People Productions. I walk out of almost any play or movie with a critical response to the technical and artistic merits of the production, but Race left me speechless.

The play occurs entirely in the law office of Jack Lawson and Henry Brown, a white lawyer and a black lawyer, respectively. Their potential client, Charles Strickland, is a rich, older white male who has been accused of raping a black woman. Lawson and Brown know that Strickland originally took his case to another lawyer, and wonder why he “didn’t handle the case in a way that he liked.” Some small mistakes by the firm’s rookie black lawyer, Susan, leave the firm with basically no choice but to accept the case. In the midst of the efforts to create a defense for Mr. Strickland, the subject of race is delved into with as much fervor as the need to prove the client innocent.

David Mamet’s script is jarring and thought provoking. I found it difficult to take notes because my mind was fixated on the themes being so forcibly, deeply, and openly demonstrated. I feel other stories I’ve encountered with race may make it central and demonstrate the conflict; they do not take it on head on trying to delve into the difficult questions that plague both sides of the equation. Mamet and the actors in this production fearlessly encounter the harsh truths that affect so much of the discussion from this subject.

Bill Gillane as Charles Strickland gives an effective performance of his character’s ignorance about his plight. While Brown says, “He’s the kind of man who has never had to beg,” Gillane portrays Mr. Strickland as a confident but not overbearing man who is unprepared for the events of the trial. Gillane is most effective in his softer and flustered moments when the lawyers try to help him realize repeatedly that he cannot make a statement to the press and that what he thought was a harmless joke with a black friend was actually offensive enough to remember years later.

The rookie lawyer, Susan, (Nasheda Caudle) is a mass of quiet determination and reflection. Especially in her numerous moments with Jack Lawson, the audience sees her really contemplating the comments Lawson makes his defense of Strickland and himself. Through Caudle’s performance, it’s clear that Susan’s influence is subtle and are empowering in her unwillingness to accept the easy answer. Meanwhile, Susan’s ability to not release her full response allows her to manipulate the situation further than those involved suspect. The only one who fully suspects her motives is Henry Brown, played by William Ferrer. Ferrer lets the incredulity of some of his lines get the better of him, but overall he has a lot to be incredulous about. The naiveté of Strickland’s’ views concerning racial joking or difficulties of separating any type of defense from race give him just cause. Some of these comments produced some of the few laughs of the evening, which whether forced or not, helped relieve some of the tense moments.

Stein Erickson as Jack Lawson provides most of that tension. Erickson lets his brutally honest dialogue mix well with the disconnect of a lawyer who understands a system but does not care if full justice is the end result. Lawson’s confrontational discussions with Susan on both the case and his actions towards her in the firm make for captivating moments. His philosophy that lawyers in a difficult case win by outperforming the competition is highlighted in his defense process, but we see his need to tiptoe when confronted directly. Erickson explored these ugly truths without making his character seem bizarre or disconnected from reality.

The confrontations are not overtly exaggerated which worked well for director Richard Scharine in the intimate space of the Leonardo Museum’s auditorium. There is not a great deal of complicated blocking; all the action happens in front of the stage, but near the end Susan takes a position of power on the stage against Lawson and Brown. This was effective considering her control at the moment. However it was surprising because that part of the stage had not previously been used. Otherwise, the tension of the words and the apt attention of the actors led to a tense two hours that never seemed slow, regardless of the legal or philosophical tenets hammered out. The attempt to create a feasible case in defense of Strickland, the inner workings and prejudices of the firm, and the way race interlaced all these discussions helped push the action forward in equal measure.

This show was full of difficult and possibly offensive material. Mamet’s language is crass and unforgiving. The subject matter is dealt with unapologetically. Days later I am still processing all of the material. But it was a singular theatrical experience that brutally approached a difficult subject. It left me in awe and contemplation and I strongly recommend those prepared for a similar experience to attend.

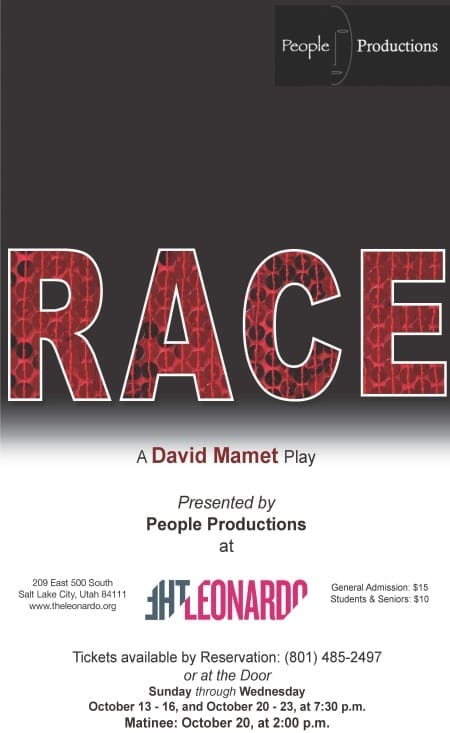

[box type=”shadow”]People Productions production of Race plays at the Leonardo Museum Auditorium (209 East 500 South, Salt Lake City) Sundays through Wednesday at 7:30 PM, through October 23 and at 2 PM on October 20. Tickets are $10-15. For more information visit: www.peopleproductions.org.[/box]