PROVO — I am always curious at the foundation of new theater companies: what niche they seek to fill in their locales and what stories they seek to tell. Most theatre companies are a result of an honest endeavor to bring something new to the masses. Happy Accidents Theater Company, a brand new troupe to the Utah Valley theatre scene, seeks to perform “honest stories presented in spaces that contribute to the performance and the overall experience of the audience.” And what a punch they packed with A Day in the Death of Joe Egg. The piece is an unconventional one, unusual for the seemingly prevalent fluff that attracts Provo audiences. The subject matter is heavier than most community theater-goers might expect, but the company so expertly navigates performance that I would highly suggest that local theater patrons take time to support this foundling company.

Comedy and heartbreak blur into a singular narrative, following the lives of Brian and Sheila. Marital bliss stands interrupted by the vegetative state of their young daughter Joe, and though both parents try to forge through the difficulties of raising an entirely unresponsive daughter, this play offers a sharp look at the realities of parents dealing with more than most people can imagine. The audience sees the complexities of Brian and Sheila’s marriage, see their desire to progress in a normal means interrupted with the absolute hardship of raising a daughter with cerebral palsy. The dreams and ambitions of a young couple stand deterred by the little girl, and though both work hard to cope with their situation, it’s clear the underlying stress and strain has put them in a difficult position.

I was particularly impressed at the subtlety of acting demonstrated by the company. Peter Nichols’s dialogue, as written, could easily veer off into a highly caricatured performance but the actors handled the story well. Mature handling of heavy content allowed for the story to relay in a naturalistic means, and made for an altogether captivating performance. Patrick Livingston as Brian maneuvered the line between humor and tragedy with a deftness I’ve rarely seen on stage. Brian’s coping mechanism of comedy elicited both raucous laughter and a heavy strain of sympathy as his situation became clearer. The relationship between Sheila (played by Kris Jennings) and Brian functioned believably; the physical touch established and cadence of speech spoke to two people that had spent a very long time living together. I appreciated Jennings’s fortitude in such a difficult role. The requirement of playing would-be loving mother, having had the opportunity for motherhood stolen away from her, presents a complexity in performance. Nevertheless, Jennings finds a sincere love for her stage daughter and husband, all the while navigating a truly distressing situation. She manages to be simultaneously hopeful and stubbornly in denial, marking her as a truly complicated woman. Sheila’s plight (as well as Brian’s) felt real—never forced, or pushed for theatricality’s sake.

I additionally appreciated the actors’ ability to manage addressing the audience directly and interacting one with another. While some greater establishment may have served well in the initial act of breaking the fourth wall, I thought the cast handled the switch between address with ease. Yet, establishing a stronger rule for breaking the fourth wall might have helped some. There were times other people on stage could hear the pieces spoken to the audience, and times when they could not, for example. Additionally, it was difficult to place the audience’s role in this piece. Are we casual observers to this relationship, or is there a greater invitation to play jury between Sheila and Brian? All the same, transitions between direct audience address and more traditional stage drama seemed to flow well. The cast handled the show’s energy well, never letting it drop.

Of additional merit was Ivan Bigney as Freddie and Julia Jolley as Pam. Their relationship provided an interesting foil to that of Brian and Sheila’s, and I was pleased to see a new shade of energy they brought to the show. Jolley provided a wonderfully bitchy undertone to the role that played perfectly opposite to Sheila’s ardent desire to do right. The dichotomy of two mothers so starkly presented against each other only provided sharper relief for Sheila’s emotional state. Finally, Lynne D. Bronson as Grace too brought distinct feminine energy to the play. The contrast of her maternal air to that of Sheila’s played in interesting dynamic, and I was pleased to see the different shades of motherhood—particularly in regard to daughter Josephine—highlighted.

Technical elements worked to provide a platform upon which the complexities of Joe Egg could unfold. Set design reflected a fairly commonplace living room, though utilized the Echo stage well. The area felt spacious, encompassing a world greater than what the stage might be expected to curtail. Costumes (designed by Angie Terburg) usually felt appropriate for the era, except possibly Sheila’s second costume because the very overt 1960’s feel made her more of a character and less an actual person. But for the most part, I appreciated the conscientious means of dressing this little slice of marital life.

In the end, I found myself very engaged and transfixed by this particular performance. The subject matter was intriguing, yes, but the profound performances of Livingston and Jennings (under the direction of Jarom Brown) made this a memorable show. A Day in the Death of Joe Egg was certainly a bold choice for this new company, but Happy Accidents absolutely delivered, and then some. I look forward to seeing the company define themselves more and hope they continue to bring forth powerful, emotionally complicated stories.

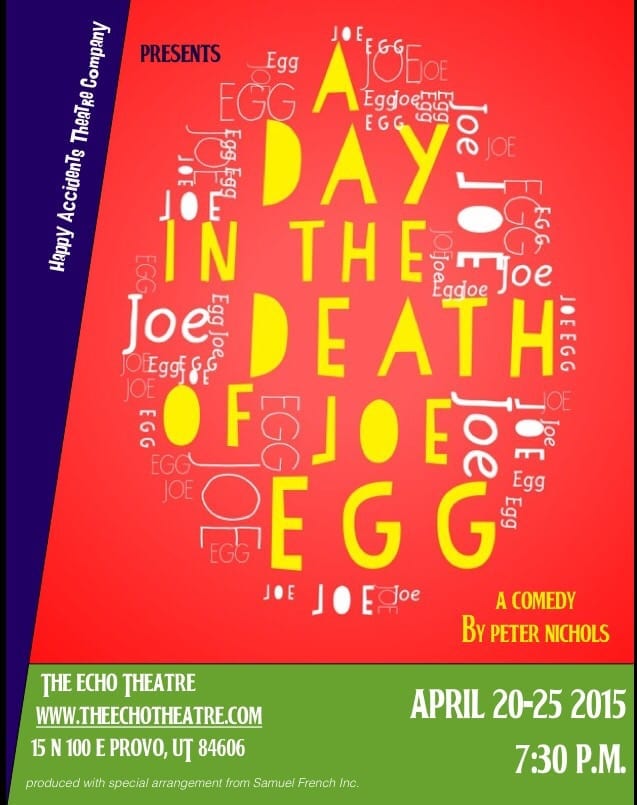

[box type=”shadow”]The Happy Accidents Theater Company production of A Day in the Death of Joe Egg played April 20-25 at 7:30 PM at the Echo Theatre (15 N. 100 E., Provo). For more information about productions from Happy Accidents, visit their Facebook page.[/box]