IVINS — The story of The Prince of Egypt is a familiar one, built on the foundations of a biblical story. Most people have some knowledge of Exodus, and the journey of Moses from adopted royal, to liberator of the oppressed Israelites in Egypt. Dreamworks released the The Prince of Egypt film in 1998, to great critical acclaim, following this same sojourn of Moses. Fans of the movie will find some noticeable differences in this re-vamped stage production, which is making its Tuacahn premiere this summer. The show, with new music by Stephen Schwartz and book by Philip LaZebnik, returns to the film’s music and basic story, but expands the world previously known to viewers. Major changes include new songs, significant alterations to the script, and additional characters (including Ramses’ wife), and conflating two priests into one. With the musical making its premiere within this last year, I was very excited to see how The Prince of Egypt would translate from screen to stage.

Show closes October 20, 2018.

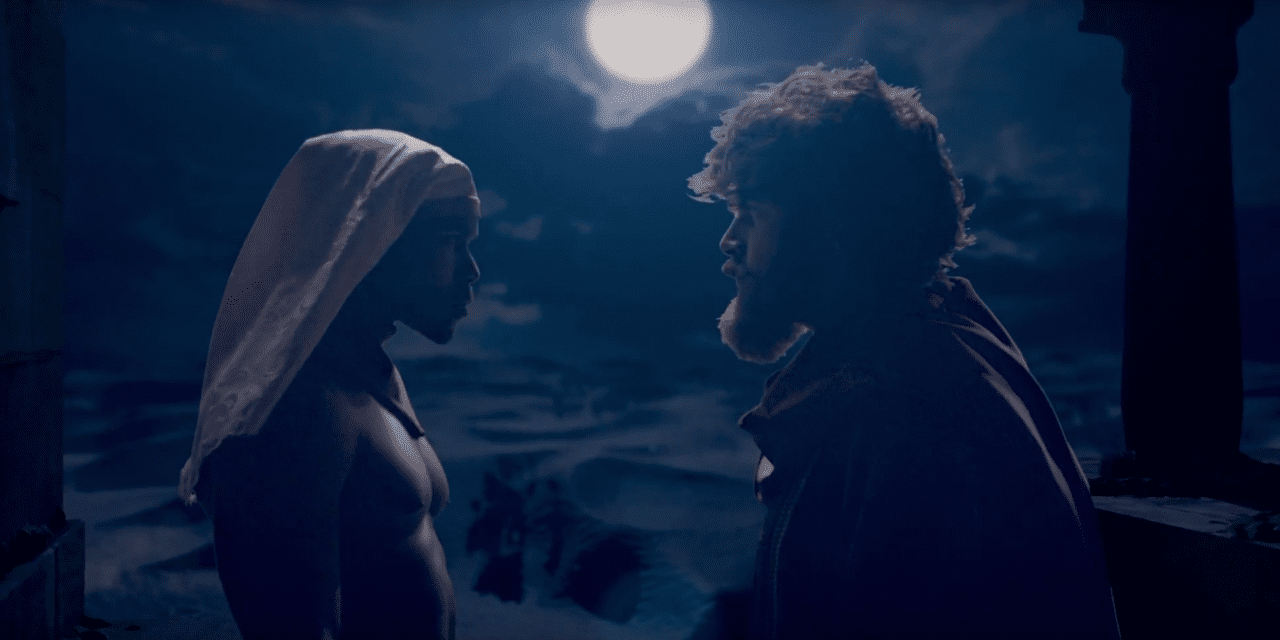

The script allows for more time to appreciate the relationship between Moses and his adoptive family. (Schwartz has jokingly noted this musical is “Wicked, with boys.”) Indeed, a large majority of the musical centered on the fraternal love that Ramses (played by Roderick Lawrence) and Moses (played by Jacob Dickey) have for one another. They are raised in a loving household, and though the expectations of royalty apply some weight, both seem carefree in their youth. Only when Moses hears the familiar lullaby of his mother does he dig deeper into his past, discovering that he is not a prince of Egypt, but the son of a slave. The revelation prompts him to view the Hebrews with more sympathy, and the emotional weight proves too much to ignore. On a construction site, he kills an Egyptian taskmaster and flees his old life. To protect the royal family’s reputation, Pharaoh Seti decrees that Moses must be killed if he ever returns. While on the run, Moses spends time with a Midianite tribe and learns to appreciate a simpler life. He is later commanded by God to return to Egypt and demand the release of the Israelites. While initially agreeing to their release if Moses stays with him, the new Pharaoh Ramses later rescinds this order when his wife and adviser tell him the weight of Egypt’s future depends upon building their kingdom with these slaves. Moses is commanded to unleash plagues on the Egyptians, driving them to desolation. Only when his son dies does Pharaoh agree to let the Hebrews go. Led by Moses, they make their way to the Red Sea, but when the Egyptian army arrives close behind them, Moses parts the waters so they can cross through the sea to safety.

The script presents some interesting new takes. Religious elements of Moses’ story are minimized, and as such, the Hebrew God almost serves as a driving force in the traditions that prompt both brothers to act against one another. For Ramses, tradition dictates he serves the pharaohs and his father; Moses must serve the Old Testament God. They seem reluctant in their roles, and fraternal love remains the strongest force in the musical. This change absolutely worked. I really enjoyed seeing Ramses in a new light, and as someone who was pushed into refusing to free the Hebrew slaves, rather than generically evil. Moses too seemed resentful of the acts he was made to perform as mouthpiece of God, and there was a scene in particular, where the guilt of ushering in the Angel of Death weakens him to the point of giving up. I have never seen or read a text where Moses feels the weight of what he’s done. The choice to have Miriam sing “When You Believe” to Moses in that moment played strongly, helping him to understand that the devastating miracles he has performed have served the greater good.

The script presents some interesting new takes. Religious elements of Moses’ story are minimized, and as such, the Hebrew God almost serves as a driving force in the traditions that prompt both brothers to act against one another. For Ramses, tradition dictates he serves the pharaohs and his father; Moses must serve the Old Testament God. They seem reluctant in their roles, and fraternal love remains the strongest force in the musical. This change absolutely worked. I really enjoyed seeing Ramses in a new light, and as someone who was pushed into refusing to free the Hebrew slaves, rather than generically evil. Moses too seemed resentful of the acts he was made to perform as mouthpiece of God, and there was a scene in particular, where the guilt of ushering in the Angel of Death weakens him to the point of giving up. I have never seen or read a text where Moses feels the weight of what he’s done. The choice to have Miriam sing “When You Believe” to Moses in that moment played strongly, helping him to understand that the devastating miracles he has performed have served the greater good.

That being said, I spoke to a friend who saw the show the same night, and for this person, the pull away from religious context made it difficult to enjoy. Without a strong relationship between God and Moses, this person said it vilified the lead and made his actions against the Egyptians almost evil, particularly when Ramses and Moses’s foster mother Tuya, welcome him home so warmly. I agree that the script almost paints God as a villain, and removes the story’s focal point from a religious experience. While this wasn’t an issue for me, viewers expecting a religious story may find themselves unsettled.

Performances were fairly shallow throughout the night, and the actors often didn’t settle into performances wholly grounded in real emotions and character traits. It was hard to connect to the emotional premise of the musical, though there were a few standout performances. As Miriam, Gabriela Carrillo found an earnestness and compassion that was truly charming. Others onstage describe her as insane, though Miriam really is just so full of hope for her people and her brother. Carrillo’s performance of “When You Believe” remains a high point in the evening. Her voice was clear and bright, and sung through with such tangible optimism. I also enjoyed Dickey’s Moses, particularly in those moments when he struggled with the emotional weight of his divine calling. It opened a point of view I had not seen before, and he played the role with growing maturity. His voice too was sonorous and carried the lyrics with meaning and purpose.

While I am normally uninterested in shows I cannot emotionally connect to, The Prince of Egypt proved an exception. The story was different and compelling to me, opening up characters that I had not viewed with empathy before. Additionally, the technical elements of this production really wowed. Costumes (designed by Dustin Cross) were stunning. The elaborate textures of the Egyptian court’s attire contrasted with the muted Hebrew’s rags and told the story of economic disparity well. And the almost-Woodstock/Gypsy vibe of the Midianites was a pleasing choice. Lighting (designed by Cory Pattak) sculpted the show with such dexterity, and really helped to define the show’s emotional tone. There were some particularly clever moments of lighting, such as creating the Nile River onstage, that impressed me. The set itself played beautifully into the ampitheatre’s setting, using the local red-rock mountains as an extension of Egypt. Gorgeous set pieces, live animals, and adaptation of the landscape really transported me and made me believe I was no longer in Southern Utah.

While I am normally uninterested in shows I cannot emotionally connect to, The Prince of Egypt proved an exception. The story was different and compelling to me, opening up characters that I had not viewed with empathy before. Additionally, the technical elements of this production really wowed. Costumes (designed by Dustin Cross) were stunning. The elaborate textures of the Egyptian court’s attire contrasted with the muted Hebrew’s rags and told the story of economic disparity well. And the almost-Woodstock/Gypsy vibe of the Midianites was a pleasing choice. Lighting (designed by Cory Pattak) sculpted the show with such dexterity, and really helped to define the show’s emotional tone. There were some particularly clever moments of lighting, such as creating the Nile River onstage, that impressed me. The set itself played beautifully into the ampitheatre’s setting, using the local red-rock mountains as an extension of Egypt. Gorgeous set pieces, live animals, and adaptation of the landscape really transported me and made me believe I was no longer in Southern Utah.

I would be remiss if I did not mention the special effects in this show. The miracles performed by Moses are easy to show in animation, but when placed on stage, can be tricky. Tuacahn’s production team and director Scott S. Anderson handled the Plagues and dividing the Red Sea so well, and both proved incredible pieces of stage magic. And my jaw dropped when fires exploded on stage, knocking over obelisks. Use of projections and lighting heightened a real sense of dread, and showed the scope of devastation well. Flooding the stage and using projection and spray to show the sea parting was an incredible moment too. Kudos to the technical team for making miracles happen on the stage.

Overall, while I wasn’t emotionally drawn into the performance, I still enjoyed my evening at Tuacahn’s The Prince of Egypt. The script certainly presents a different story than I’d heard before, but the changes prompted a lot of thinking and conversation after the show. I liked being able to view Pharaoh Ramses more sympathetically, but with no real villain to fight against, it was easy to question Moses as a hero. Combination of technical elements, beautifully stylized dance movement, and Schwartz’s music sung so beautifully was enough for me to forgive the acting and remain invested in this production. I would highly recommend that viewers make the trip to Tuacahn (though, bring a fan to fight the heat) and see this different take on an old story.

Donate to Utah Theatre Bloggers Association today and help support theatre criticism in Utah. Our staff work hard to be an independent voice in our arts community. Currently, our goal is to pay our reviewers and editors. UTBA is a non-profit organization, and your donation is fully tax deductible.